I’ve just come through a brief Dorothy Whipple phase. Only two of her books so far, but it’s nice to know that she is there in the wings if I’m ever stuck for something to download. Another interwar author (I can’t get away from them) but this time with a focus on the North and the Midlands. Very readable, with plenty to interest and keep me thinking. It chimed with Lucy Malleson’s autobiography: a sense of cheerfulness and modesty that keeps one grounded without being walked over, and always the spectre of real poverty in the background.

High Wages (1930)

Set in a northern town before, during and after WWI. A young woman, alone in the world and having to make her own living, is taken on in a classy draper’s shop and works her way up to her own shop selling ready-made clothes. Whipple has a warm, engaging way of writing that is nonetheless sometimes a little flat-footed and sometimes too contrived. The first page, for instance, when the reader is introduced to Jane . . . and risks confusing her with basil fotherington-tomas:

The whole expanse of heaven was covered with minute clouds, little abrupt things, kicking up their heels, flying off into nothing. They were so madly inconsequent that Jane laughed. And then, as if someone had said to them, ‘Come now! Quietly! Quietly!’ they stopped rioting and settled down together in the rosy glow. They were merged and gradually were lost to sight. A majestic gold arose and suffused the sky, leaving a pool of green in the east.

but it gives you an idea of Jane’s spirit – and, fortunately for her future wellbeing, her idealism is tempered with common sense and an eye for what is fashionable and becoming.

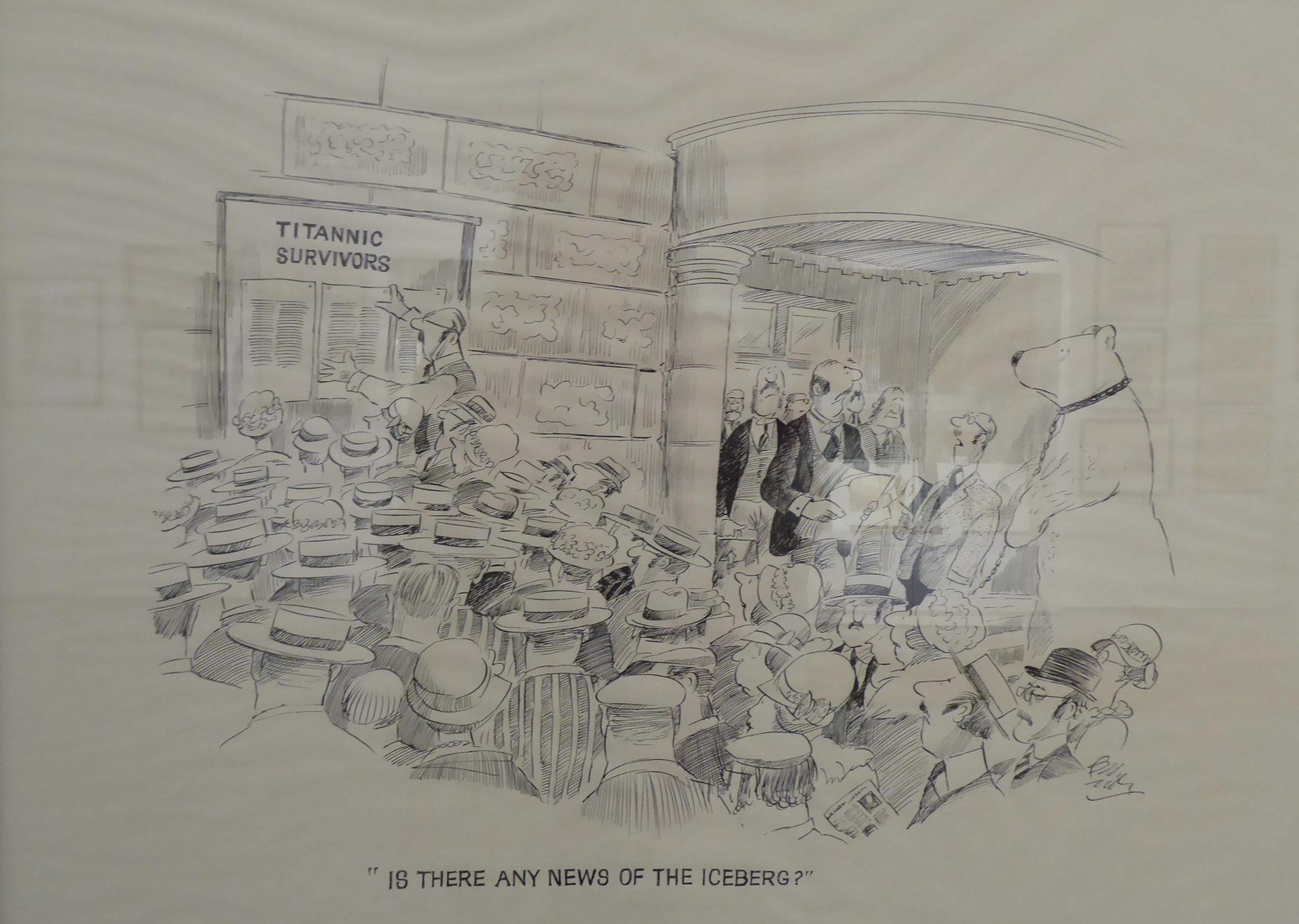

The novel is focussed on the female perspective of the world; a narrow place where choosing fabrics and clothes is a pleasurable escape. The war happens offstage; Jane’s concern is her tiny new shop. The plot, such as it is, is unremarkable; it’s the sense of lived life that is the novel’s great strength, particularly when seen through Jane’s eyes. It’s also very good on the accommodations we must make with real life: having to put up with an employer’s miserliness; overcoming distaste at a co-worker’s habits and focussing on her friendliness; the courage required to step outside your preordained sphere.

The Priory (1939)

A family living in a country house, once a priory, beyond their means, all equally self-absorbed. Into this stagnant life the Major drops a little pebble – a new wife – in the hope of having a household better run than his sister can manage, and the ripples spread far and wide. I thought of it as a novel about imperfect marriages – one where, on the eve of war, various couples fight their own little battles until they arrive at some kind of armistice.

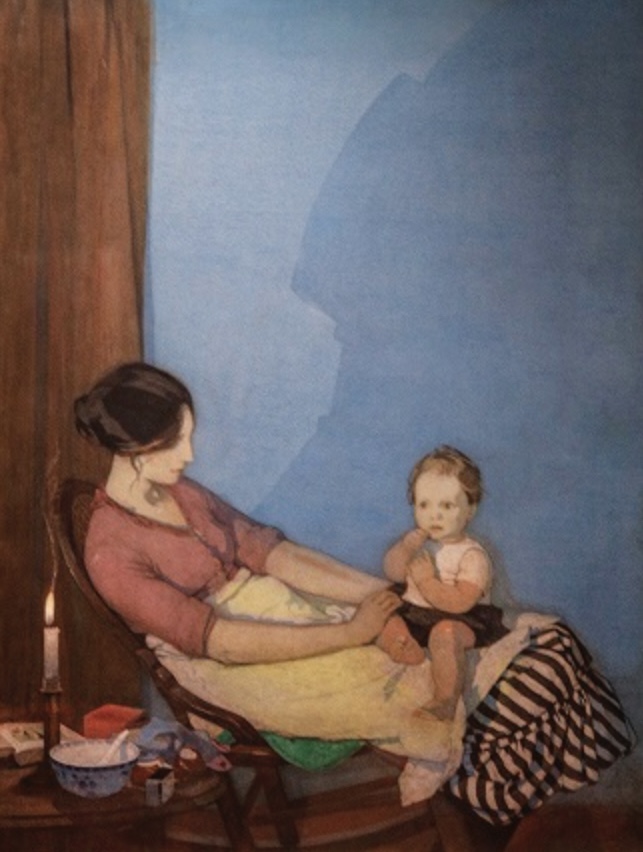

Once again, Whipple is good at ambivalence. Nurse Pye is a monster when she discovers Bessy’s pregnancy but a ministering angel when Christine’s baby has pneumonia. Anthea, the new wife, is really quite a sympathetic character but seems unsympathetic as she gradually eases out each limpet from the house. That’s the best of shifting free indirect speech: the reader has an insight into the feelings and motivations of each character.

There’s a sly amusement in some of the lines and a sense of seriousness in others. Anthea on her enduring quest for happiness:

She remembered a phrase from one of her old books on happiness, in which the necessity for effort was dwelt upon. “Everything worth while,’ said Nietzsche, ‘is accomplished notwithstanding.’ Anthea acknowledged it; notwithstanding [her husband], it was in her case.

Christine’s thoughts on the place of her family’s home and grounds:

She saw for the first time that the history of Saunby was a sad one. It had been diverted from its purpose; it had been narrowed from a great purpose to a little one. It had been built for the service of God and the people; all people, but especially the poor.

‘And now it serves only us,’ she thought.

In the old days, the people from all the villages round about had come to Saunby for help and advice. They had brought their sick and their children. They had come up the avenue and down the drive and the back drive and in at the side from Byford and Munningham. Travellers had broken their journeys at Saunby, and pilgrims rested on their way from the north to Canterbury and on their way back.

It’s the kind of run-down country estate that, post-war, might have been bought and turned into council houses, a school, a surgery and a little parade of shops – a mid-20th-century version of the community that the Priory once offered. As it is, the novel ends with a plan to make Saunby into a privately owned community offering home and work – a rather bolted-on happy ending that was probably what readers wanted in 1939.

But perhaps that was an improvement on the contemporary class-based way of helping people. There’s a bit of a broadside against Lady Bountifuls, those upper-class women who acted as unofficial social workers:

Penelope put down her chocolate cake. Now they should have it.

“You see, I don’t believe in what you are doing,” she said in her cool voice. “I don’t believe in playing with the poor.

“You’ve grown out of your dolls, so you take to the poor. The poor are an occupation for you. Getting up bazaars is fun for you. You haven’t any affairs of your own, so you go and interfere in the affairs of the poor. You go and visit them in their dreadful houses and portion out allowances for a little food and coal and clothing and then you come back to a home like this and eat a tea like this.”

Which is probably the kind of thing that Lucy Malleson was doing in Stepney. The more I read, the more I can see why the country was ready for some kind of socialism in 1945.