The Mersey wind cuts with a sharp knife: I tucked everything around me as I headed down to the river. The open views of the famous riverside buildings have been redacted by the big blots of modern buildings – but the latter do provide good reflections. Having watched Terence Davies’s “Of Time and the City” a couple of weeks ago, I remembered the overhead railway, and reflected that the waterfront has probably never presented a perfect view. (But the Cunard Building tried hard!)

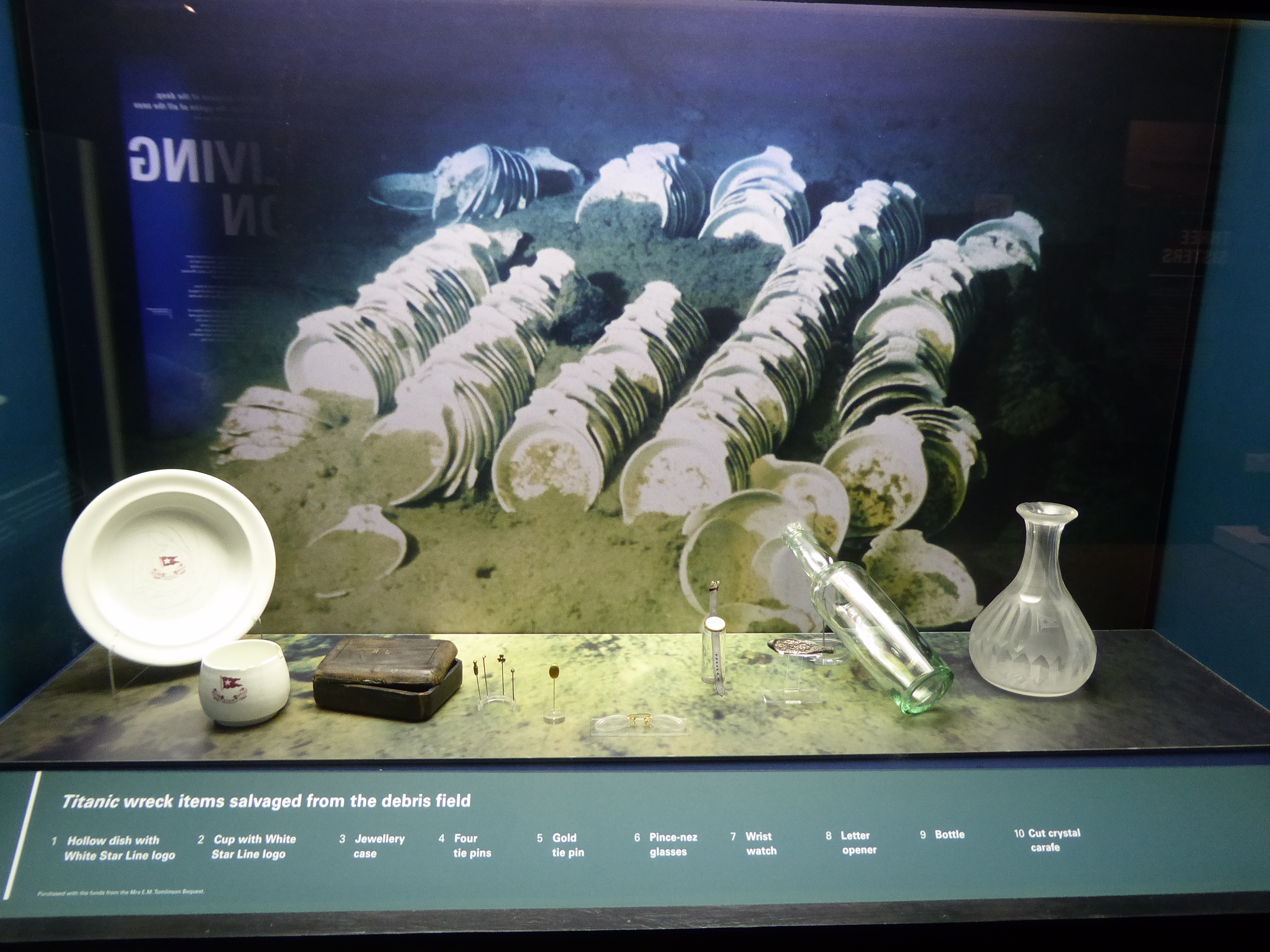

To the Maritime Museum, where I found myself unexpectedly interested by the history of Liverpool’s docks. More expectedly, I was very taken by the glamour of interwar ocean liners. The Titanic exhibition I largely swerved because of school groups, but the photograph of a rack of plates, still on the sea bed and half-covered by sand, was surprisingly moving. A modern Vanitas.