An organised walk on a grey, drizzly day along the towpath. It sounds dull, but the recent weather has almost amounted to house arrest so I was glad for the prod to be out of doors.

An organised walk on a grey, drizzly day along the towpath. It sounds dull, but the recent weather has almost amounted to house arrest so I was glad for the prod to be out of doors.

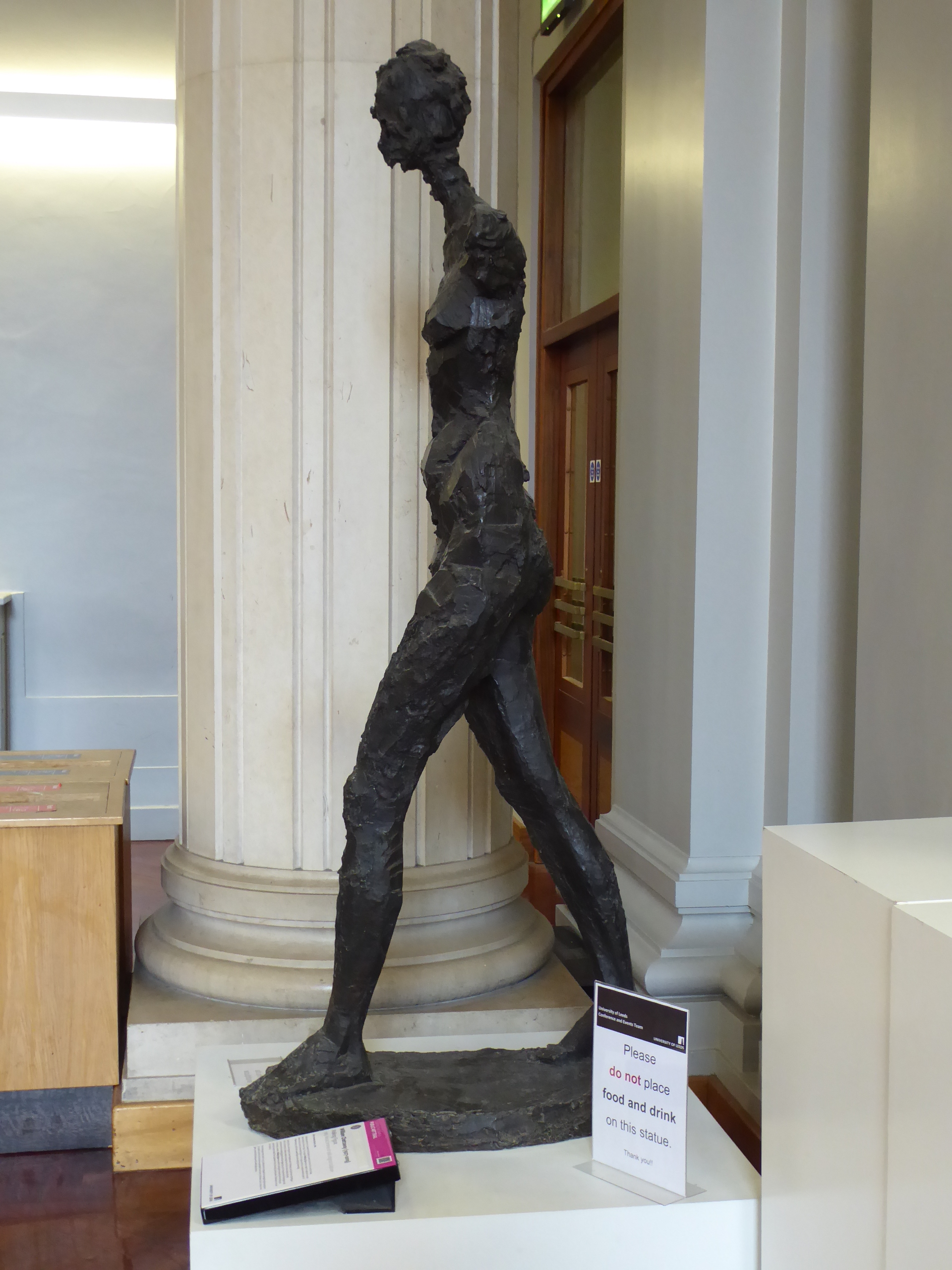

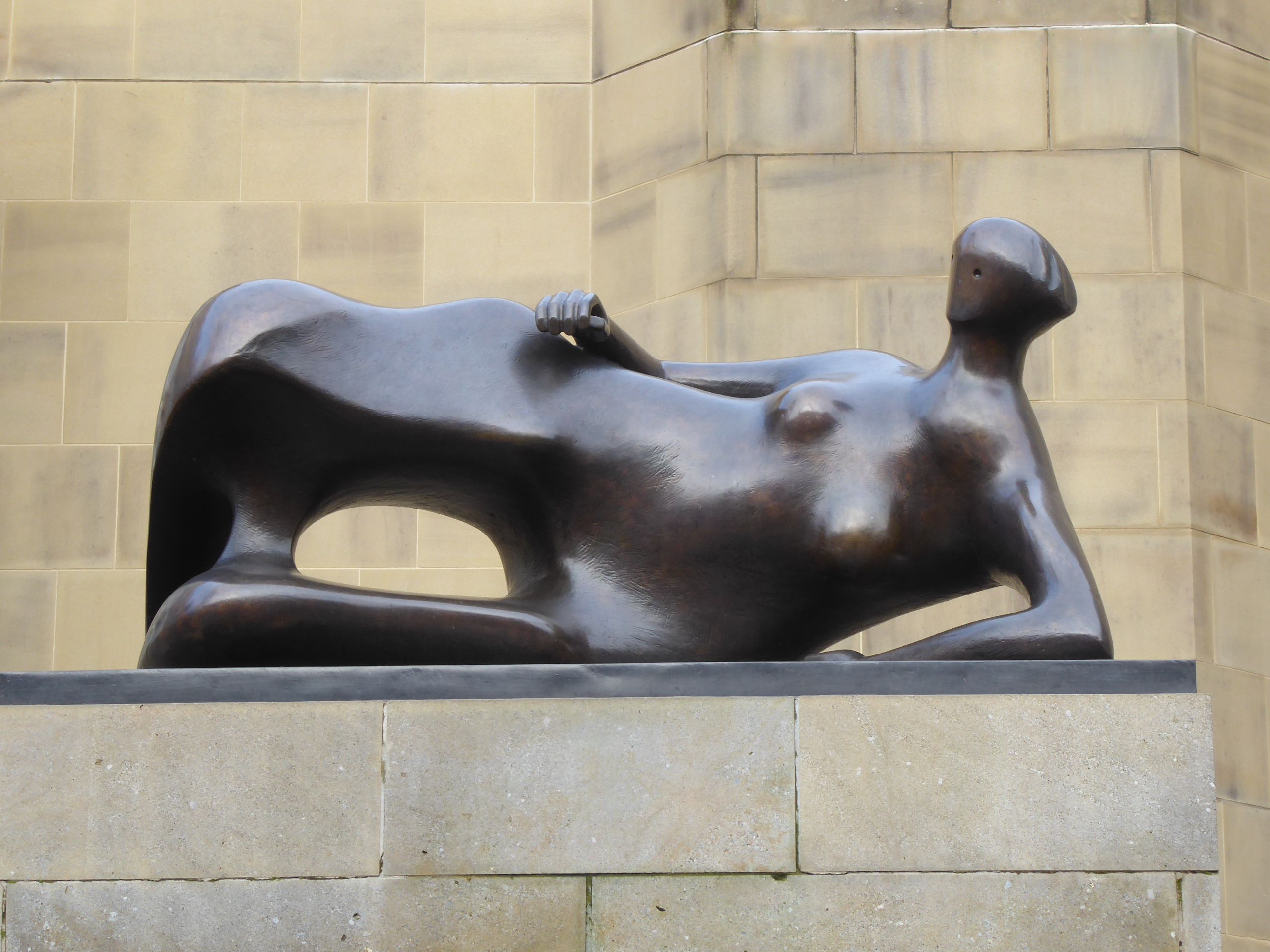

Over Christmas I’d watched Alan Bennett’s play “Sunset Across The Bay” from 1975 on BBC iPlayer. There’s a short scene of the bus passing City Square and the old man remembering when the statues were seen as “right rude”. (Heavens, how dirty the Queens Hotel was then! And the nymphs have moved around.) I’ve always rather liked the statues and I’d noticed that there were a few more barely-clothed figures around, so I looked out for them on my walk to the University.

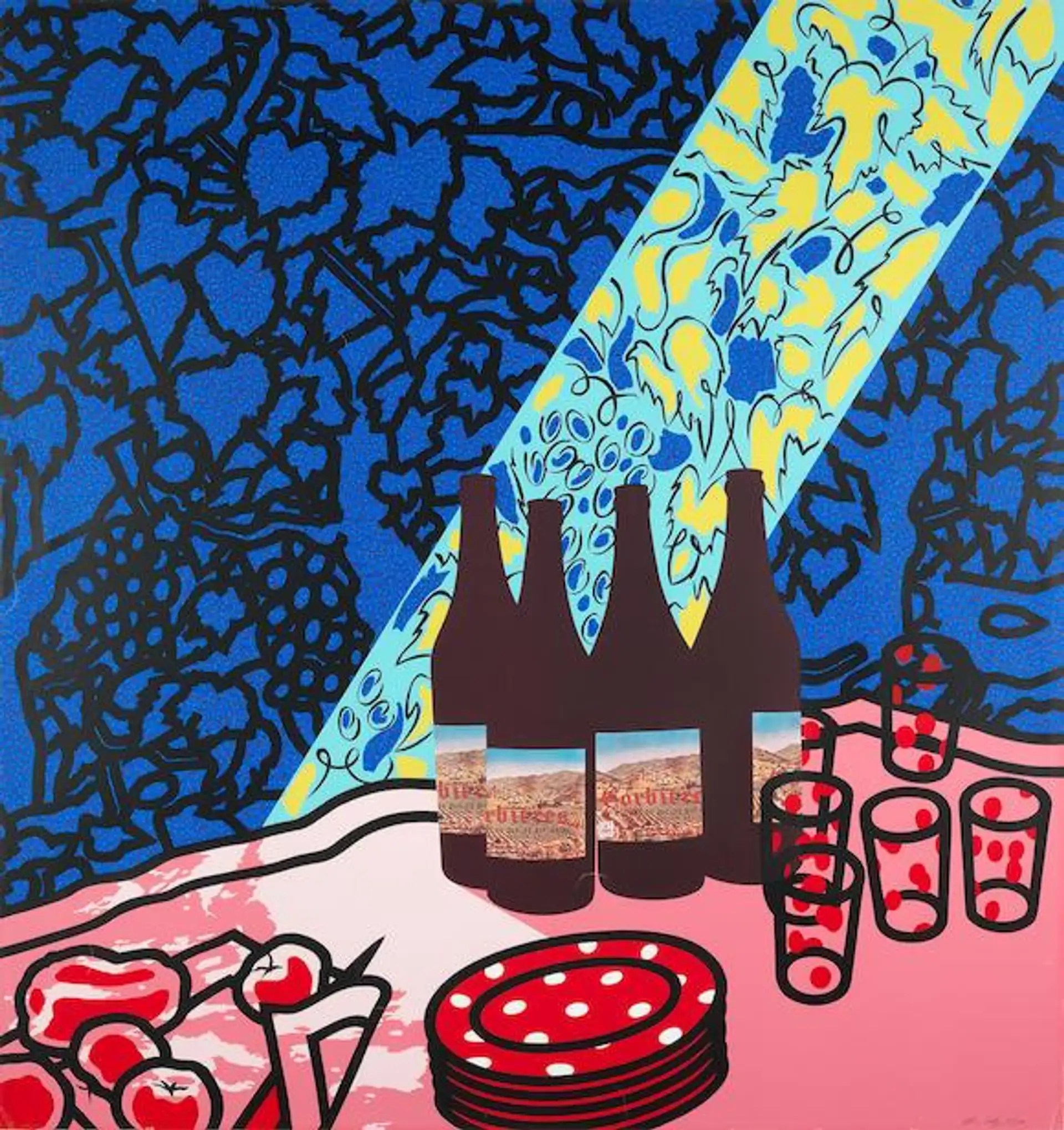

The Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery has had a change since I last visited. I was oddly taken by the work of Judith Tucker – insignificant, commonplace landscapes that are very familiar and deserve more attention. Then a painting by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham that – despite being “Untitled” – struck me (after a night at the opera) as representing three cellists. Even though I knew it wasn’t, I still stuck to it. And there was a figure by Bernard Meninsky, whom I’d come across in Hull. Not inspiring, but I can add him to my mental list. (Matthew Smith and Jacob Epstein were there too, looking very Smithy and Epsteiny.)

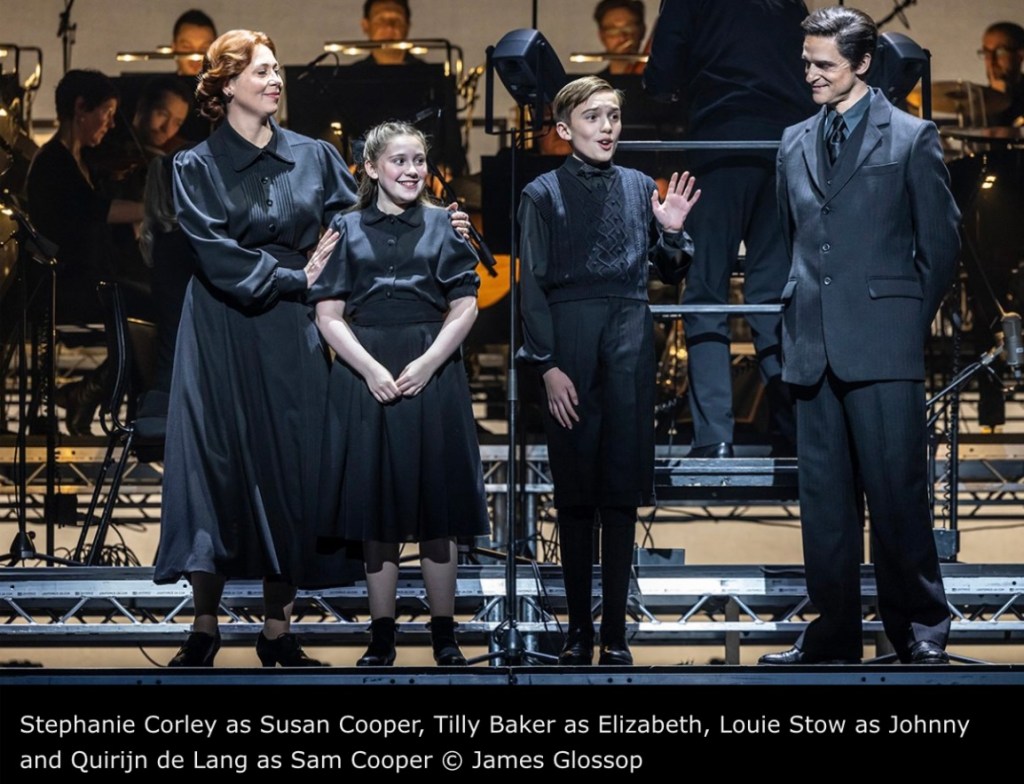

Well I certainly didn’t expect to find a link between The Travelling Players and this exuberant musical, but I did: Brechtian devices.

Music is by Kurt Weill, lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner. It’s a “concept musical” – no plot to speak of, but a theme runs through it. The theme here was marriage: a single marriage stretched across a century and a half, seen against the economic and social forces of the time. In 1791 everything seems simple and homespun: love, a home, a livelihood, neighbours. Perhaps there is a sense that life could be “more”, but circumstances make it implausible until industrialised progress arrives. Then come factories, taking the husband out of the house for long periods each day. Then come railways, taking him away for long periods each year. Then all the opportunities of the twentieth century . . . to become a hustler, a consumer, a self-fulfilment machine. And what about her? Always at home or demanding a vote and a career? And when the career is really just a job that tires you out by the time you return home – what then?

The musical was framed in a vaudeville show, with each act as a kind of Zeitgeisty Greek chorus. It also ensured that it was great fun. How can you not warm to a male octet singing jauntily about progress or a male quartet on economics? Had the audience known the words, they would surely have joined in with the Women’s Club Blues! The orchestra was up on stage as the backdrop, and I began to think of the conductor as a big band leader.

Director Theo Angelopoulos

Having just seen one film from the Mediterranean made at the tail-end of a repressive regime and looking back on recent history, I thought I’d try another.

Both films were slow, but The Travelling Players beat The Spirit of the Beehive hands down in that respect. I realised how beautiful and human the latter was as I sat through the chilly scenes of a Greece filmed in grey and beige and inhabited by what seemed like marionettes. (That day’s paper had a feature on holidays in Greece with clichéd azure skies and golden beaches; Angelopoulos drained such scenes of all colour.) The camera was sometimes very, very still and sometimes pensively surveyed its surroundings, looking at everything in turn.

It was a film steeped in Greekness. The troupe’s play was “Golfo the Shepherdess”, a bucolic tragedy performed in traditional dress. The manager was betrayed by his wife’s lover; both the wife and her lover were later killed by her son, Orestes, with the assistance of his sister, Electra. Greece itself was betrayed by the Allies after the first and second world wars (and, implicitly, during the rule by the junta). Fortunately I knew enough Greek history to make some sense of the film, and on three occasions characters broke the fourth wall to give a brief account of, say, the Smyrna catastrophe. The viewpoint was very left wing; the British didn’t come out well from any of these little history lessons, and there was a minor revolt as American music drowned out the Greek accordion at a Greek-American wedding feast.

The style was detached: characters were generally seen in long shot, framed in or dwarfed by their surroundings. The film’s prologue was the accordionist’s prologue from the play. Sometimes the camera lingered on a street while the years moved forwards or backwards: thus 1952 became 1939 without a scene change. Often I had the impression of a stage set – particularly for the civil war scenes of street fighting, where opposing groups of fighters advanced and retreated across the “stage” like gangs of rod puppets or shadow puppets (Karaghiozis?). There were repetitions on a theme: Golfo’s fear of the shadow of a man had echoes in several scenes of shadowy figures seen to one side. I found no humour or lightness, but there was a surreal quality at times – the snowy hen hunt, for example – which might have passed for humour. The film’s beginning was its ending: the reformed troupe arrives once again in Aegio after 13 years.

Everyone agrees that the film is a masterpiece, so I shan’t demur. I found it austere and unyielding, like the gaze of the military busts you find in Greek town and village squares – but interesting withal. I created my own pleasure in lapping up what had once been such familiar sights to me: whitewashed stone buildings, double wooden doors, terracotta roofs and akroteria, periptera, ankle-twisting pavements, painted signs, railway station architecture . . . oh, everything.

Yesterday’s visit to the British Museum altered my focus today. I’d intended to see the exhibition on medieval women at the British Library, but now I was bursting to see a separate exhibition of some of the artefacts taken from the Library Cave at Dunhuang. I managed half an hour before a school group arrived and it was utterly fascinating.

How come I’ve never heard of Dunhuang?! But in a way I find my ignorance inspirational: there may be heaps of other wonderful serendipitous discoveries still to come my way.

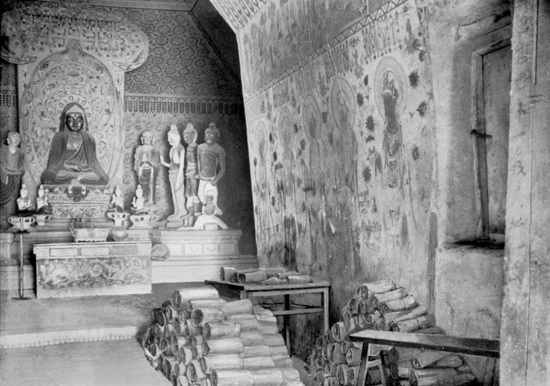

So: Dunhuang is an oasis town, once a garrison on the edge of the empire controlled by the Han dynasty. It has several Buddhist cave sites around, including the Mogao Caves (first caves dug out around 366 and more over the next thousand years), which look utterly amazing. The only – comparatively puny – comparison I could pull out from my own experience was Mystras or the monasteries of the Meteora.

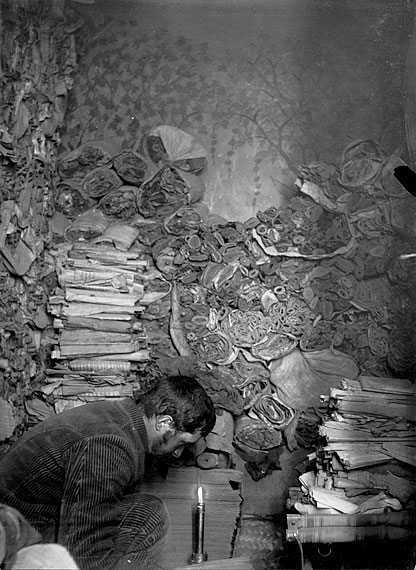

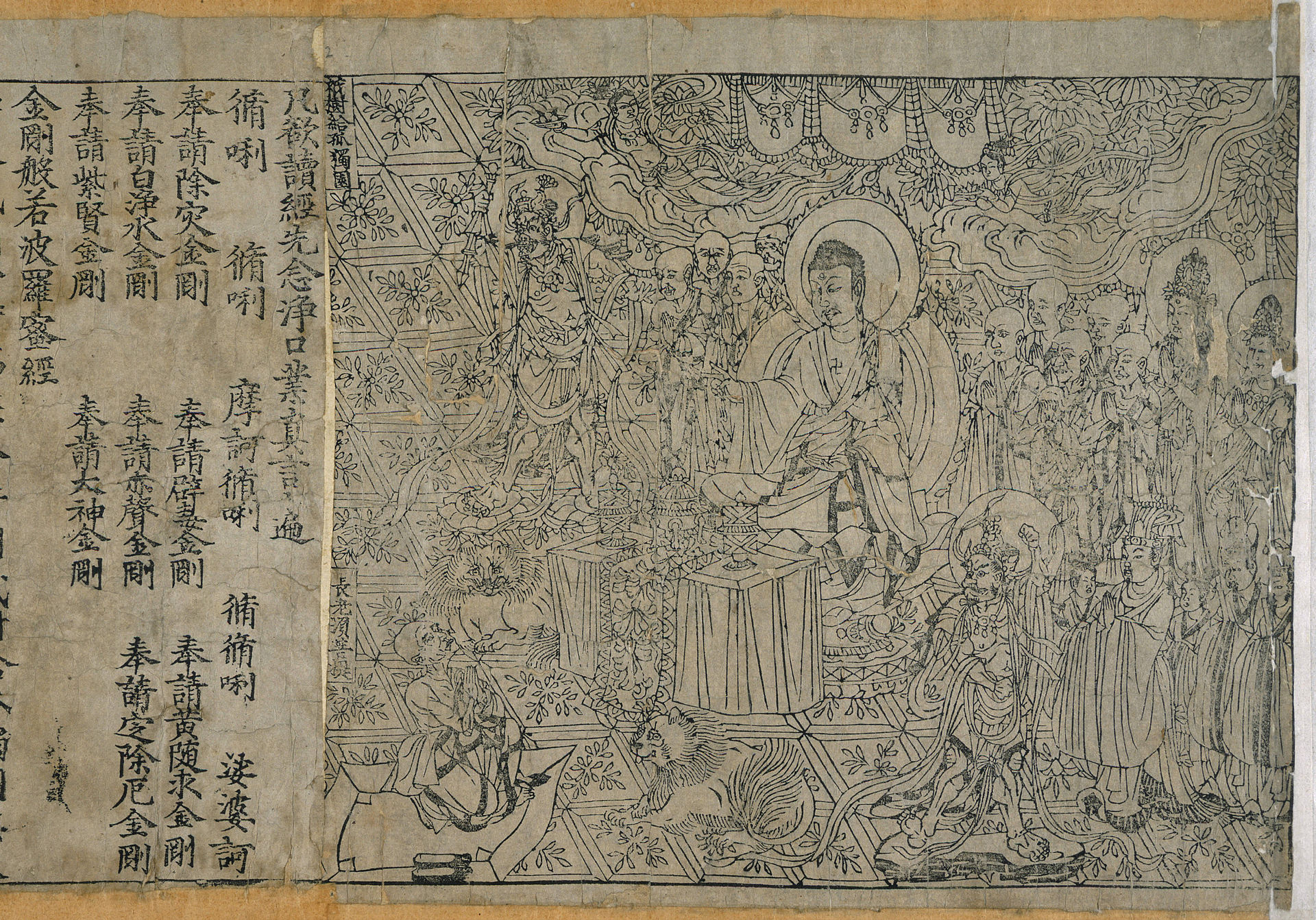

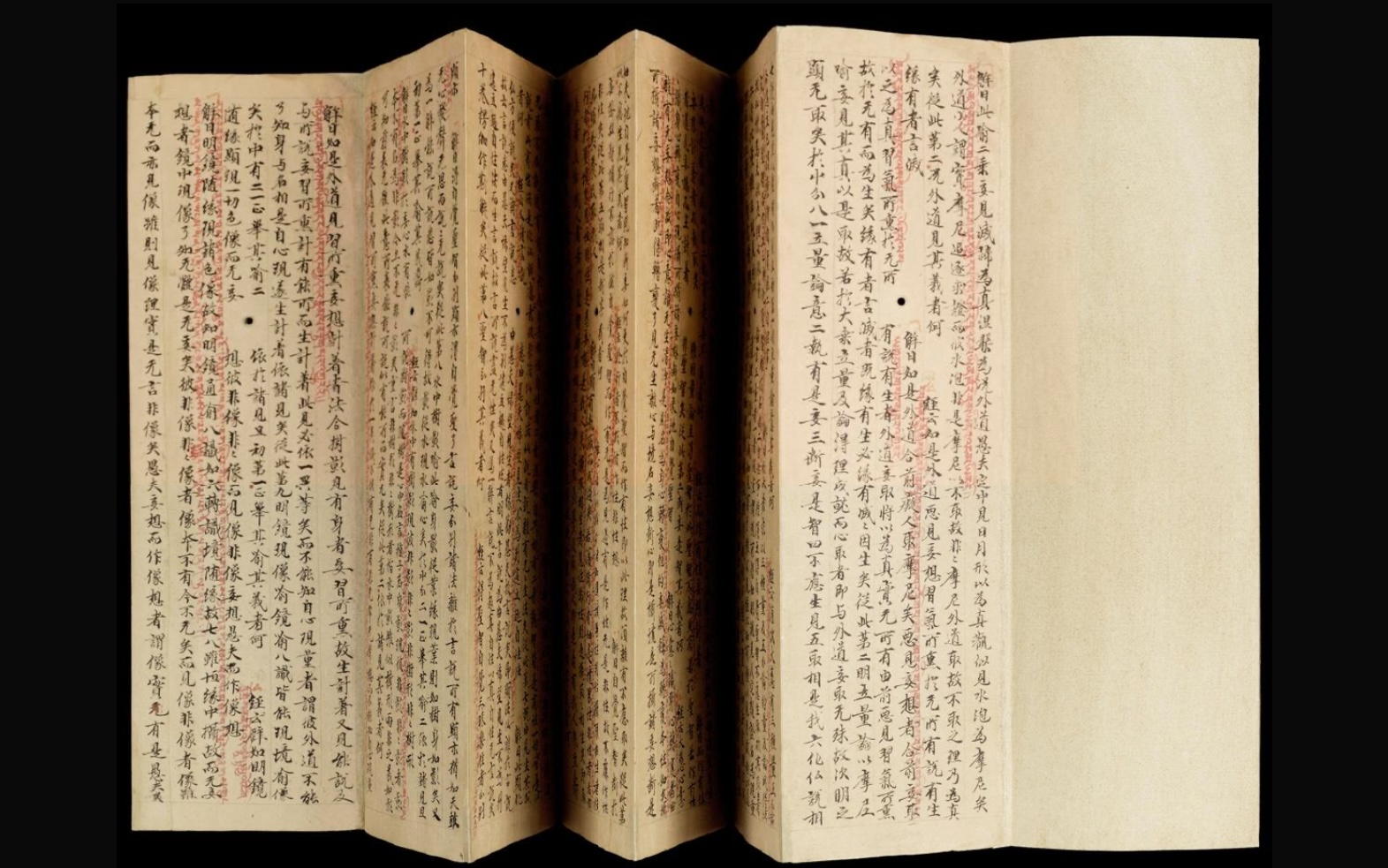

The Library Cave (cave number 17 of more than 700 caves) was discovered by a Taoist priest, Wang Yuanlu, in 1900. It contained some 50,000 documents of all kinds, both religious and secular, dating between 406 and 1002. Marc Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-British archaeologist (whose life story sounds fascinating), acquired many of them and brought them to Britain. This included – deep breath to take it in – the Diamond Sutra, the oldest complete printed book with a date in the world.

Which I took a photo of.

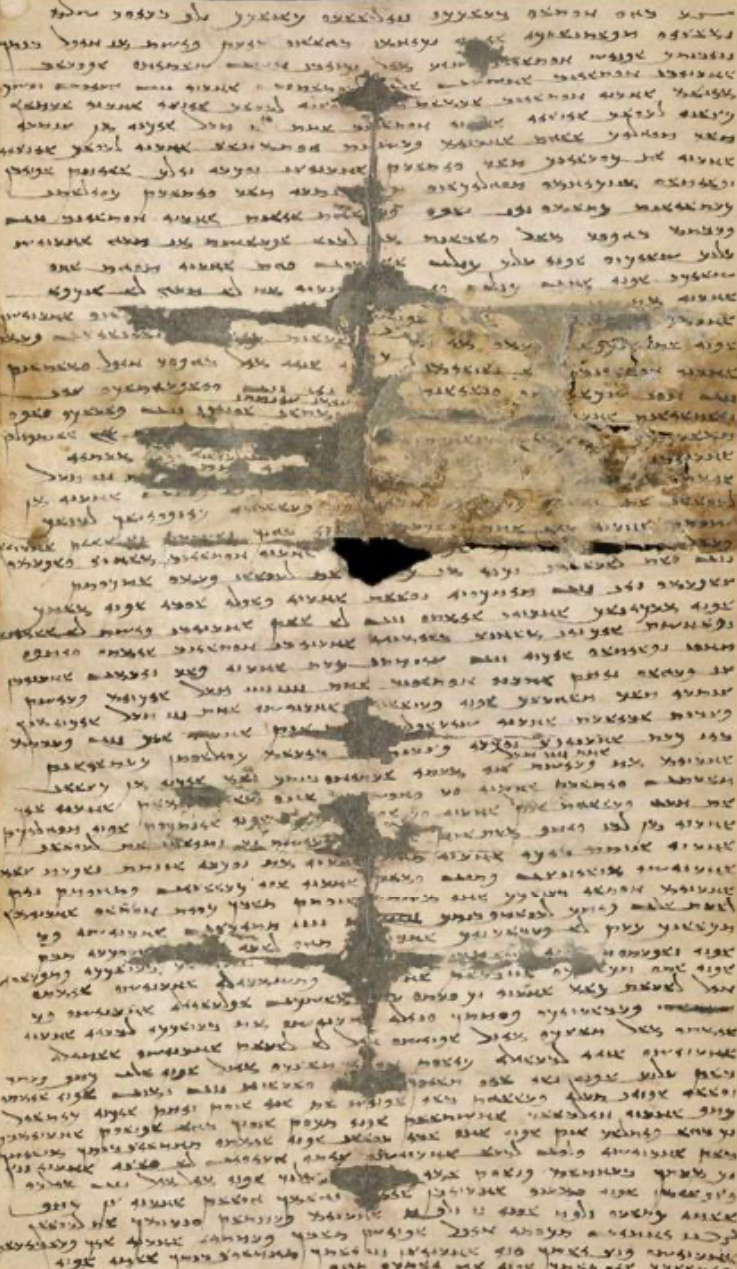

There were phrase books (crucial at this multi-lingual crossroads), Tibetan sutras copied out by local scribes (which gave an impression of what work was to be had), artists’ designs, letters between merchants and families, woodblock prints, almanacs, etc etc. Unable to understand a word, I focussed on the charm of the pieces: the holes in the much-folded letter from a merchant, the concertina-ing of a bilingual manuscript which could be read horizontally or vertically depending on the language.

The exhibition underlined what I had grasped yesterday: that goods are not the only things to travel along trade routes. Religions, ideas and practices are just as significant.

After this, the exhibition on medieval women in their own words seemed dull and predictable. My only amusement at the time was in discovering that a charm made from weasel testicles was considered a contraceptive. I appreciate the scholarship that goes into all this, but, really, Jane Austen put the words into Anne Elliot’s mouth over 200 years ago:

Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands.

On reflection, that is a very unfair and sweeping judgement, for it did contain some astounding items: a letter dictated by Joan of Arc and signed by her, for example. And the thread of religious mysticism kept me wondering: was Margery Kempe unusually pious, a charlatan, or had she found her own way to escape the bonds of a medieval woman’s life?

My geography failed me completely here. I doubt I could pin Japan on a map, let alone Korea or Uzbekistan. I realised how completely flummoxed I was at having no Eurocentric compass to orient myself at the start of the exhibition as it began with China and dynasties I had never heard of. I encountered lots of new information, which is still sinking in; it may be a while before the dust settles to reveal coherent thoughts.

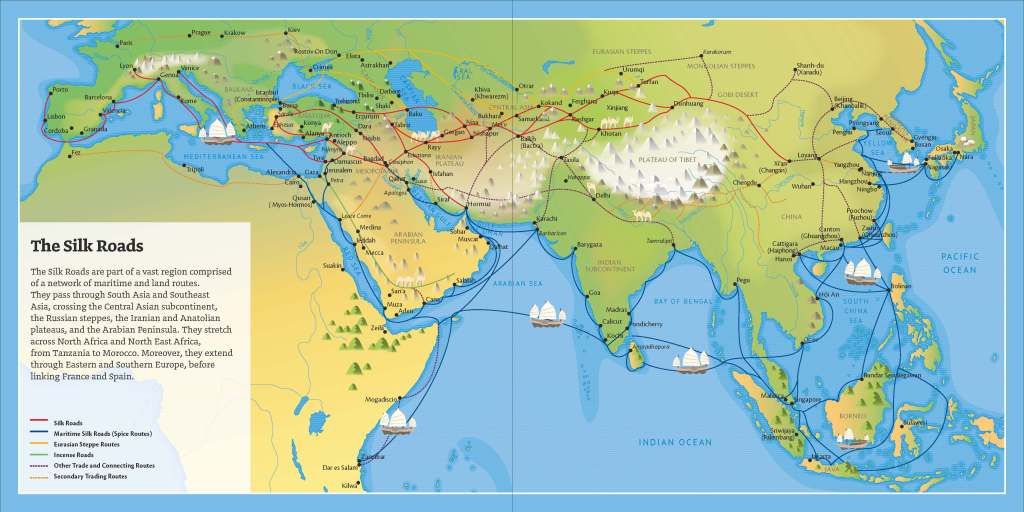

Λοιπόν. This exhibition at the British Museum focused on trade routes between Asia, Europe and Africa between 500 and 1000 along which silks, spices, luxury and everyday goods, and ideas passed. It began with a bronze figure of the Buddha – made in Pakistan in the late 500s and excavated in Sweden amongst buildings dating from the 800s.

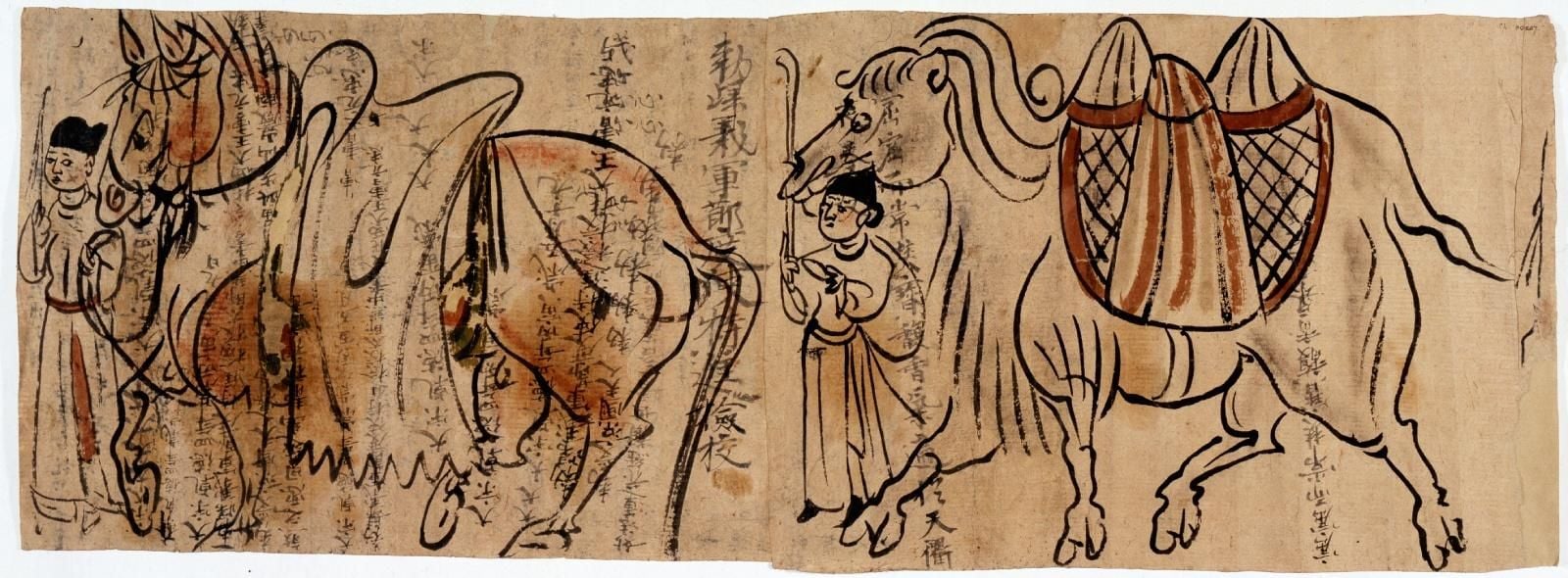

First: the developing links between China (Chang’an), Korea (Unified Silla) and Japan; in the Nara period (700s), rulers in Japan adopted elements of the Tang dynasty and adapted the Chinese writing system for their own language. Buddhism spread eastwards from India at this time to become the dominant religion. Silk was used as currency in China, and it was one of the luxury items in demand along the trade routes.

I found out about Dunhuang, a garrison town, where in 1900 a sealed “library cave” was discovered, containing manuscripts, textiles, paintings and other objects. Empires and peoples I had never heard of were represented by wonderful objects: the Sogdians, for example, and a mural from Samarkand showing a Sogdian ruler and his entourage, or one of an elephant from the Bukhara region.

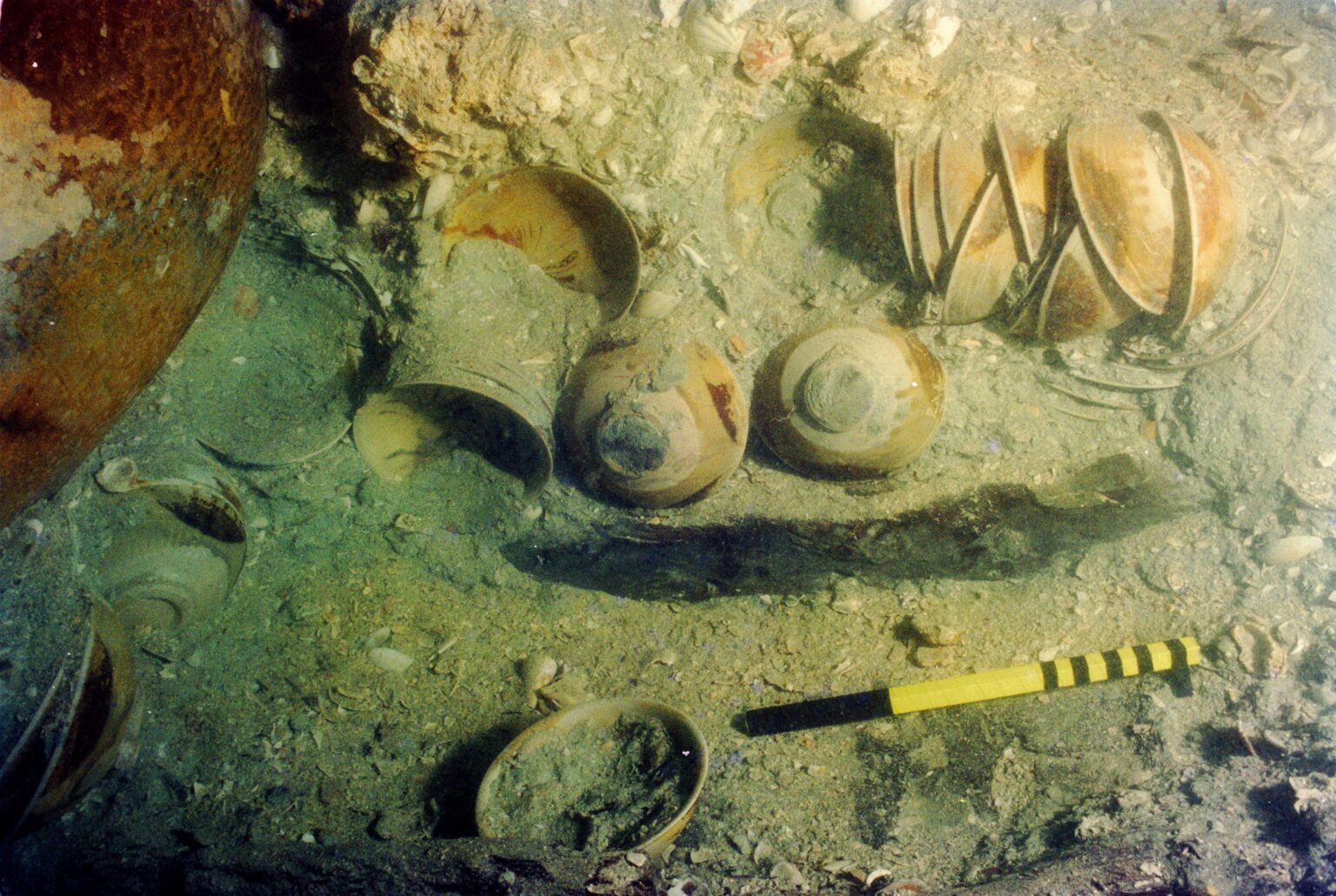

The Belitung shipwreck was fascinating and mind-boggling. In 1998 a shipwreck was discovered off Belitung Island in Indonesia; a vessel from the early 800s en route from China to perhaps the Arabian peninsula, containing over 60,000 items – mostly Chinese ceramics. (The photographs of crockery on the sea bed reminded me of the Titanic last month.) I could happily find a home for the pretty blue and white dish – which makes clear how the very human pleasure of acquiring attractive objects as well as the essential stuff like salt drove so much global trade.

Ideas, religions, technological knowledge and languages travelled along the routes. There was a concertina of a Buddhist sutra in both Chinese and Sanskrit and a fragment of New Persian text written in Hebrew script; I had to think hard about those. Religions that travelled along the route: not just the dominant Buddhism of this time but also Hinduism, Manichaeism and Zoroastrianism, meeting up with local deities and religious practices, and, later, Islam through conquest.

Such a sense of human activity over so many centuries! Some of it illustrated our worst tendencies: the never-ending desire for more and more luxurious goods and the trading of people as well as commodities.

By the time the silk routes reached the shores of Europe, my sense of wonder diminished: it was all rather familiar. On reflection, I realised how thoroughly and unusually immersed I had been in an exhibition that barely touched on Europe or parts of the world colonised by Europeans. It doesn’t often happen, and it did make me very aware of my ignorance and lack of a compass as I venture into new territory.

After lunch I returned to more familiar territory: a small exhibition of prints and drawings that Max Beckmann had given to Marie-Louise von Motesiczky.

My mistake: I went to the museum hoping to see the copy of David Copperfield that accompanied Scott and his men on the Terra Nova expedition, but that’s not until February.

No matter: I was able to photograph some of the coal hole covers I’d noticed before in Doughty Street.

The museum was quite interesting. Dickens and his wife lived there from 1837-39; they arrived with one child and left with three. It’s an early-Victorian middle-class house with a few items of furniture that came from Dickens’s final home in Gads Hill. I confess that what really grabbed me was a portrait of Catherine Dickens with an overmantel in her lap. In a display case below her was an overmantel that she embroidered some years later – which sent me back to Tirzah Garwood and her endless creations. The difference was that Garwood made her own designs and sold her work, but the image of two women across a century with hands forever at work remained with me.