I have finally got round to cycling from Keswick to Penrith on the Brompton. It’s only taken me two years.

I have finally got round to cycling from Keswick to Penrith on the Brompton. It’s only taken me two years.

Director Robert Bresson with Martin LaSalle

The polar opposite of The Brutalist: spare, short, black and white, non-professional actors, affectless dialogue, no images just for the sake of beauty or imagination, characters always dominant in the frame as far as I recall. (Well, except for the close-ups of the pickpocketing scenes, which were like dance interludes.)

No introduction, no backstory to the characters. Raskolnikov by Camus is my take. The written autobiography of a young man who decides to become a pickpocket. He’s not very good at first but meets (gets picked up by?) a professional who shows him how to do it properly. (There will be locks on all my pockets from now on!) He refuses to see his dying mother until the very end, he ignores the possibility of a job offered by his steadier friend, and he taunts a police officer with his theories that criminal masterminds are justified in their actions since they are superior to the rest of society. Doesn’t believe in God, almost gets caught and flees, returns to Paris two years later having spent everything on gambling and women, finally gets caught and sent to prison. Sudden change of heart when he accepts the love of the girl who befriended his mother. Fade out on repentance. Sin and atonement, with the road to redemption – as so often – relying on long-suffering females.

Much has apparently been written about Bresson’s disdain for “acting”, but his alternative of stilted delivery of lines left me unmoved. The pickpocket’s voiceover telling the audience how the thrill of stealing from under people’s noses made him feel truly alive was belied by his expressionless face and sullen demeanour throughout. No doubt contrary to Bresson’s intentions, I looked behind the story to the incidentals: the grimy garret, the tap on the landing, Parisian crowds, a slice of life at a particular time and place.

Once again, all the critics thought it wonderful.

Director Brady Corbet with Adrien Brody, Guy Pearce, Felicity Jones

“Overblown” is, for me, the only description. The final words of the film – “it’s the destination, not the journey” – were so bombastic that, like one last blow of its own trumpet, they widened the existing fractures and the whole edifice came tumbling down. (Unless it was some meta-joke, welcoming the viewer – at last! – to the end credits.)

It started off well: Hungarian-Jewish architect is released from a concentration camp and sponsored by his cousin to move to a new life in Philadelphia. Fairly menial work for a long time until he is taken on by a rich, obnoxious-beneath-the-veneer man who has a grandiose scheme of his own. Eventually – after several years apart – the architect’s wife and niece are able to join him from behind the Iron Curtain. Things like that really made you feel the duration of post-war suffering for people already damaged by the war. The images were wonderful and striking, the acting was great, and I was hooked until the interval.

After that, too much was piled on. As a film about the building of the New Jerusalem (whether metaphorical or the founding of the state of Israel) and the Jewish experience in a new country that still despised you as the old one had – yes. Overweening ambition à la Citizen Kane – not so much. An architect driven by beauty, proportion and space – well, OK, but it’s a bit of a tortured genius cliché. The seductiveness of the vast wealth of the post-war US was tangible and woozily shot, but that look of beauty stretched to everything. The doss house, shovelling coal, life in a wheelchair – all beautifully framed and shot. (The 1980 epilogue really looked a documentary film from the 1980s. Technically brilliant.) That started to grate. How many more shots of the sunlit cross on the altar did we need? The years in a concentration camp were almost irrelevant until the end, when it was revealed – far too late – that the size of camp cells had been the inspiration for designs. If you’re going to focus on boxy and enclosed spaces for over three hours, give the audience a clue a bit earlier on. And – excuse me – born in 1911, studied at Dessau and a celebrated architect before the war? That’s stretching it a bit.

But all the reviewers think it’s wonderful.

Director Akira Kurosawa with Takashi Shimura

This was the original of Living, which I found very moving, so nothing in the plot was new to me. Instead I noticed the differences: Shimura’s range of facial expressions, which were more like those of a silent-era actor. The young woman was still full of joie de vivre, but here she was coarser. The camera work during his night on the tiles was dizzying and full of reflections.

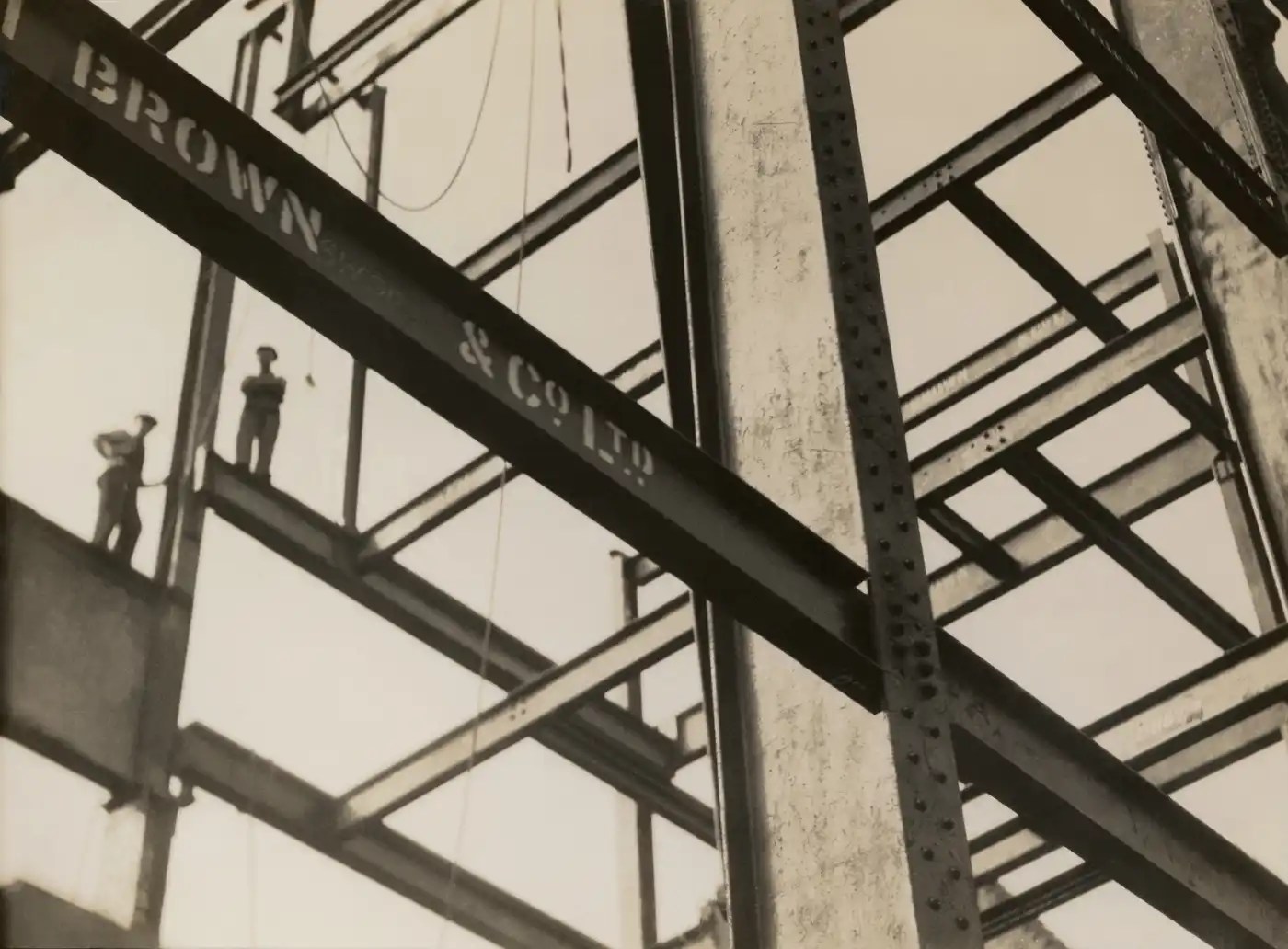

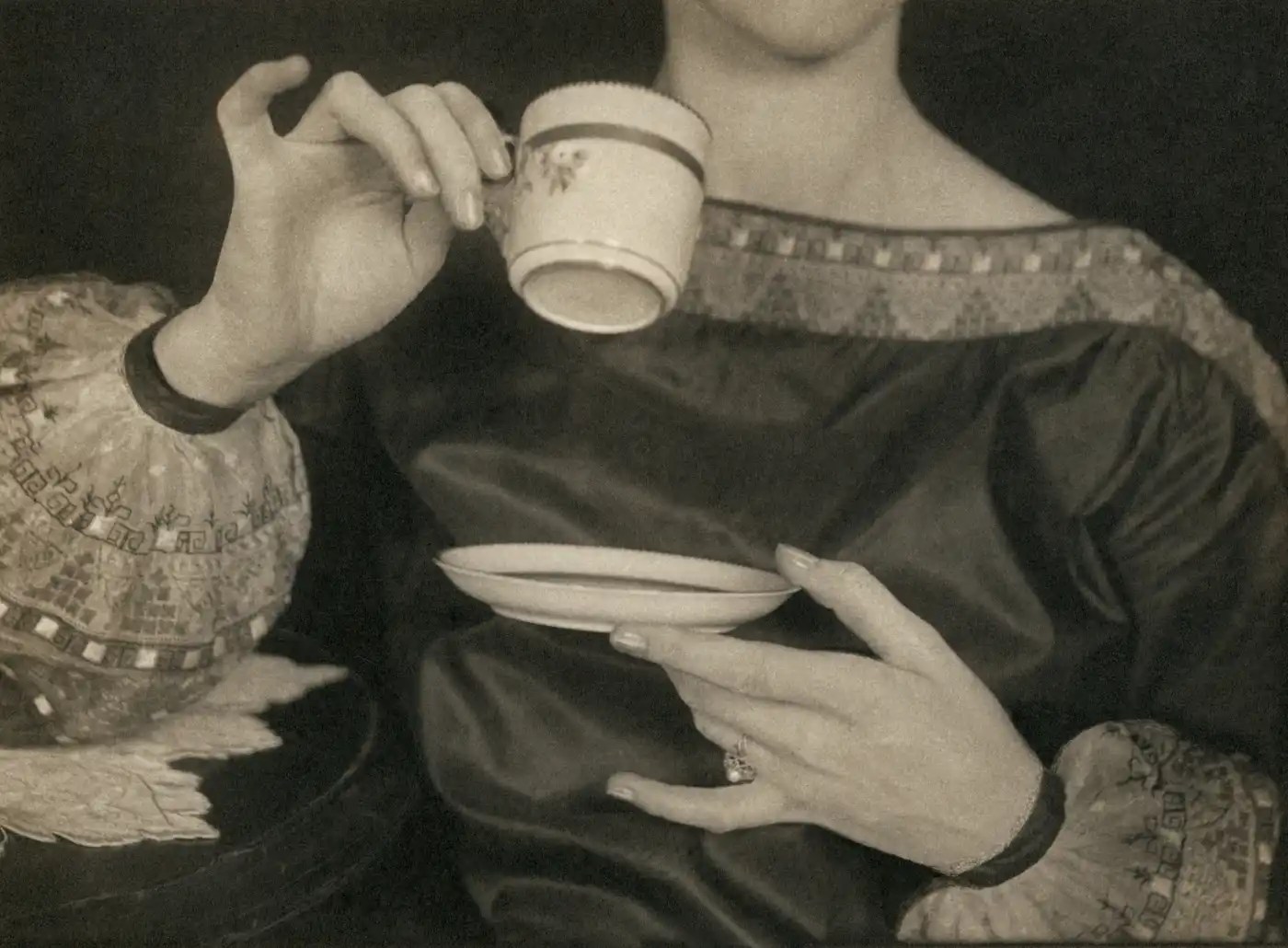

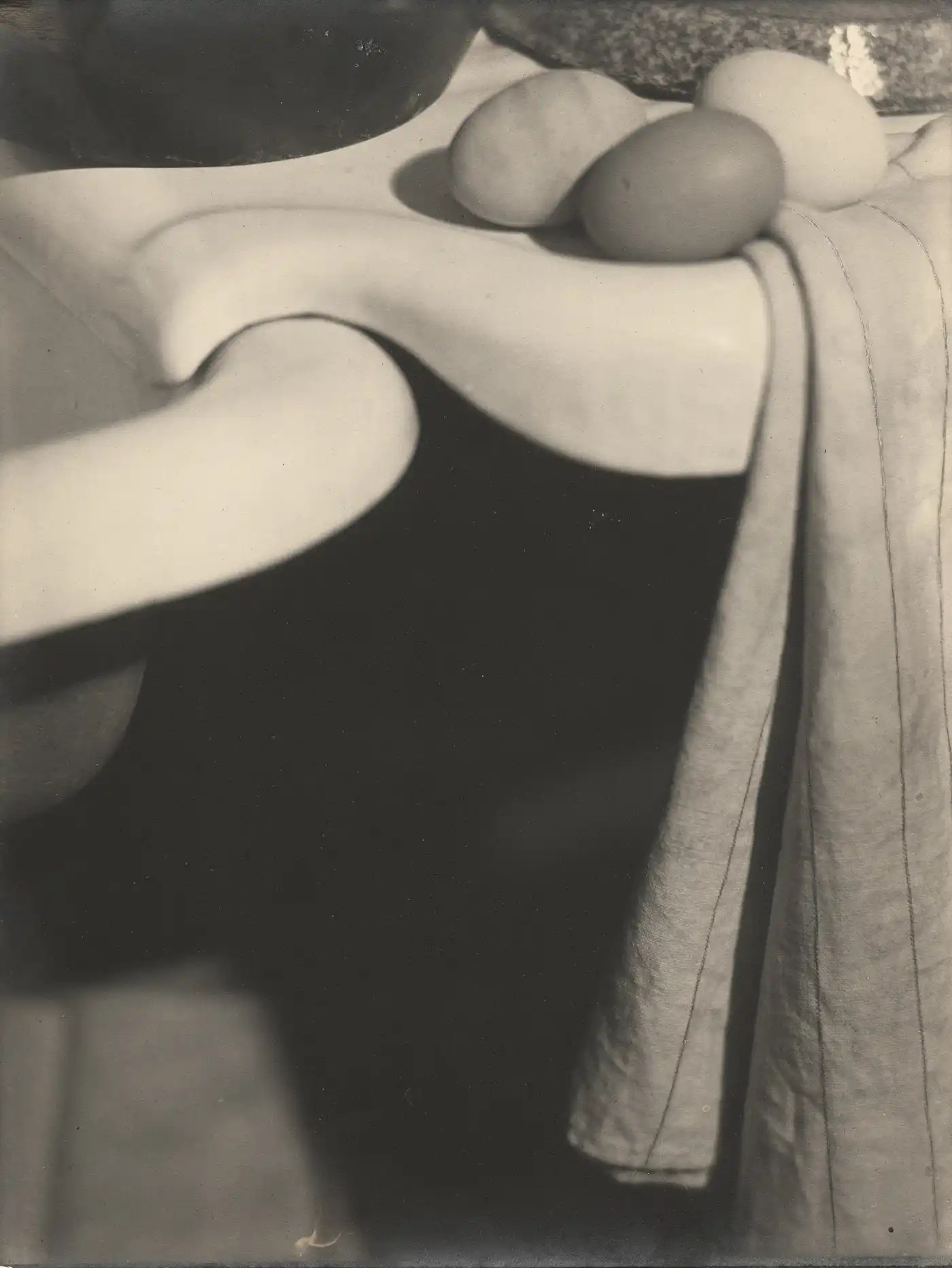

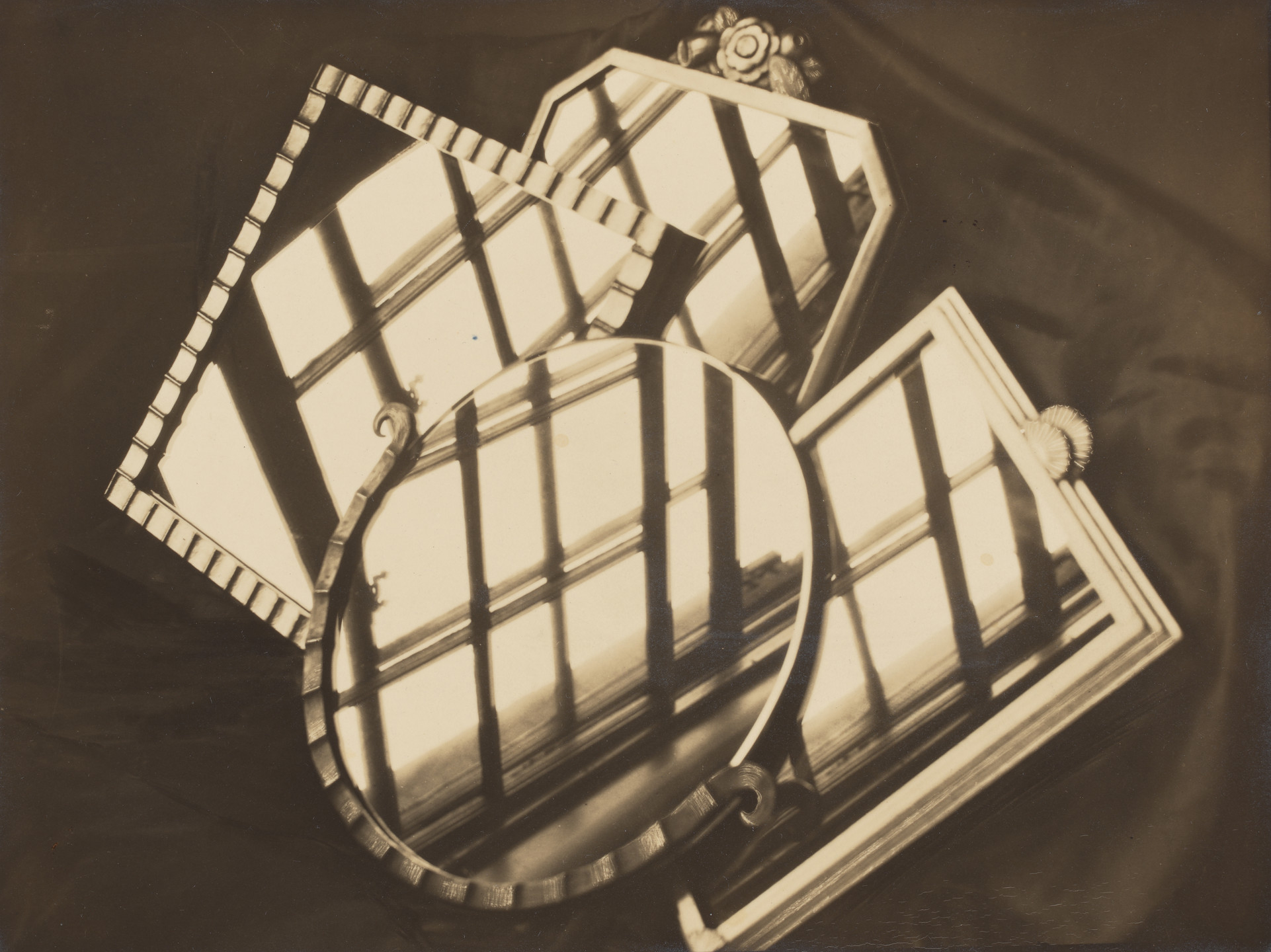

A few weeks ago I read about Margaret Watkins (1884-1969), a Canadian photographer who lived, worked and taught for several years in New York before travelling to Glasgow and getting stuck on the flypaper of domesticity. In New York she found success in advertising and in offering a new kind of abstract “kitchen sink” composition. The three eggs was the photograph that gripped me: the curves, the dark space – just wonderful. Strong geometry and sometimes a painterly style. (The dainty tea cup photograph is advertising cuticle cream.)

So off I went to Glasgow on a freezing day trip to visit the Hidden Lane Gallery off Argyll Street. En route I discovered – and was taken aback by – the City Free Church. I didn’t think Presbyterians went in for that kind of thing. It’s by Alexander Thomson and is currently unused – and what would you use if for now?

A quick visit to the Burrell Collection afterwards, where my steal would have been a Persian rug to bring the garden indoors in winter. I realise from my choice of photos here that I am longing for spring and the sense of nature re-awakening.

Director Ryusuke Hamaguchi

. . . but bad things happen nonetheless. It started off so slowly and (I confess) dully: tree canopies, then more tree canopies. But not beautifully shot, as the tree canopies in Perfect Days. A man -Takumi – chopping wood in the snow, expertly splitting the logs with a single blow of the axe. Men collecting water from a spring and taking the cans to their cars, stopping briefly to collect some wild wasabi. A public meeting about the construction of a glamping site and discussion about the siting of a septic tank. Banal talk in the car about jobs and dating apps. And yet . . .

It became mesmerising and thought-provoking. A small community in a forest where spring water is their drinking water and the forest provides their fuel. It’s not primitive: their cars are four-wheel drives. The public meeting was crucial to the unfolding of the film, with Takumi pointing out the importance of balancing the environment with human activity. The glamping site, as proposed, would pollute the drinking water and the inevitable campfires would pose a danger to the forest. I thought afterwards that the way scenes were framed embodied this balance; at first I had thought them dreadfully mundane, but actually there was a balance – for example, between the trees, the snow, the house and the 4WD. The same with the long, banal shots through the back of the car window: the tarmac road receding, but balanced on either side by the forest and at the top by the snow-covered mountains. Characters were often seen moving behind thick trunks or obscured by high banking – a small blob in the wider environment. The short interlude in Tokyo was completely the opposite: the occasional verticals of intermittent tree trunks were replaced by the domineering verticals of nothing but office blocks.

Nobody actually wanted to “be evil”. The Tokyo company representatives didn’t want to upset the delicate balance of the forest and human activity. Takahashi didn’t intend to startle the deer that (presumably) attacked Takumi’s daughter. Takumi didn’t mean to forget to collect his daughter nor to hurt Takahasi. The deer didn’t want to attack. And the glamping site was a means of accessing time-limited subsidies rather than ruining a community’s drinking water, so it just “had to” go ahead for the sake of the company and employee’s salaries. (Hmph.)

Shades of Italian neo-realism; I read afterwards that the actors were not professionals. That would account for the expert log-splitting.

It’s still very cold, but the snowdrops, early crocuses and winter aconites have been out for a while and I thought it was time to head into the garden again. My main task was pruning the soft fruit bushes, but I pottered a bit as well. By the end I had a pile of stuff for the green bin – some of which was too nice to be thrown away immediately.