I’m not sure I’ve ever been in the Science Museum before; if I have, I would have been a child. (I’ve definitely been in the Natural History Museum, but not for over 50 years. Maybe it’s time for another visit.)

This exhibition was about science and bling – what you can do if you are an absolute ruler with vast resources at your disposal. Thanks to Jean Plaidy, I already had a general idea of the generation-hopping longevity of the last three Louis – Louis XIV (1643-1715), his great-grandson Louis XV (1715-1774) and his grandson, Louis XVI (1774-1792). They were great promoters of science and technology as well as the arts. Their reigns cover the Enlightenment and the publication of the Encyclopédie (1751-1772), and I came away with the impression that everybody at that time was discussing Newton’s Principia (1687), looking through gilded telescopes (1750) and ticking off what they could see from Cassini’s map of the moon (1679).

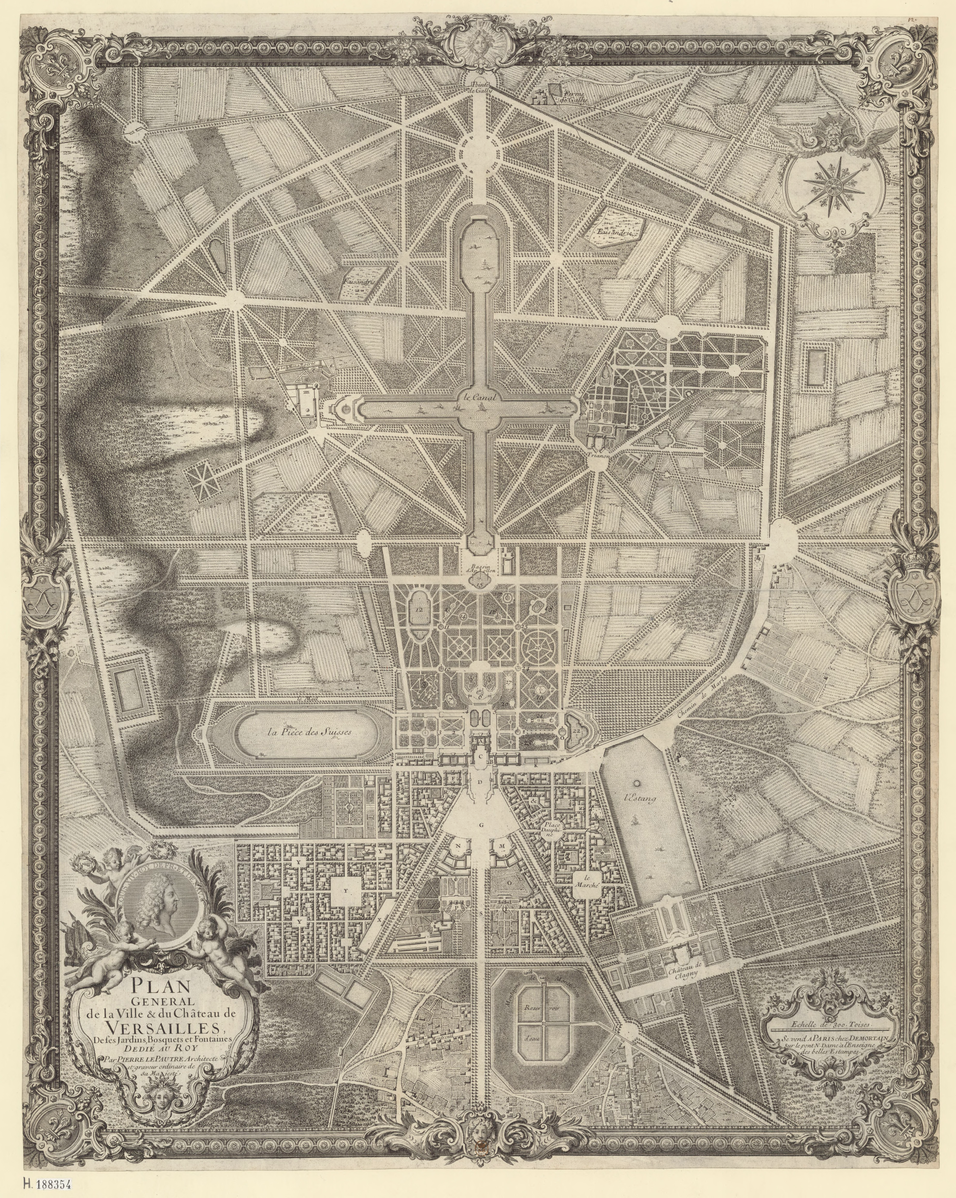

I don’t mean to be facetious. With their immense wealth and power, they were like the pharaohs of Egypt; instead of pyramids, Louis XIV constructed Versailles and its far-stretching gardens – all of which required accurate measurements and engineering. How else could you ensure that the two octagonal pools, 1.7km apart, would appear to be the same size to the king when he looked out of his palace window? Entirely frivolous – but knowledge and skill combined with human labour to make it work. Channels were constructed in the Seine to feed the monstrous Marly Machine to take water uphill to the Versailles fountains: ditto. Horology was crucial – not just for timepieces but to calculate latitude and longitude on the long sea voyages that kept the French empire close. Cassini was enticed from Italy to become the director of the Paris Observatory; he spent eight years observing the moon and to produce his map. He and his descendants also produced a map of France, and it was fascinating to see the triangles stretched across the land to ensure its accuracy. Thinking of Cassini, though, reminded me how knowledge is often in flux and needs constant checking: he began his work at a time when the heliocentric theory was still debatable, and, for all his brilliance in his other discoveries, he was the originator of the suggestion that Venus might have a moon.

Botany and zoology flourished at Versailles. Louis XV was presented with an Indian rhinoceros in 1769 – and here it was (stuffed; another victim of the French Revolution). There were fashions for plants, with Madame de Pompadour popularising Turkish hyacinths, but there was also scientific analysis and recording. Surgery was progressing: there was a display of the slender scalpel that Louis XIV’s surgeon developed to treat an anal fistula along with the small device that looked like an instrument of torture to ensure . . . no, really too much information. But it does bring home to you the uncomfortable reality of how advances are made. (The surgeon “practised” on a few dozen unfortunates with the same condition. Presumably most of his later patients at least must have survived for him to have the confidence to go ahead and tackle the king.) There was a life-sized hand-sewn model of a womb and foetus for the training of midwives: it looked like the kind of doll that a mother might sew for her daughter – which, under the circumstances, seemed appropriate.

Pingback: Vanessa Bell and Charles Dickens | Old Shoe Box