It was such a nice day and I was ready so early that I decided to walk towards the river and pick up the train somewhere en route. After yesterday’s crowds around Covent Garden, I opted for Gray’s Inn Road and Holborn, which I was sure would be deserted. I’m still infected by the locations in Hidden City; walking stirred memories of what I know about London – my own experiences (here I used to cycle, there I attended someone’s Call to the Bar) and what I have read (fact and fiction). I stopped to photograph Holborn Viaduct not only because of Hidden City but also because I recalled a line from a novel:

‘Of course I don’t expect you to come. You’ll do as you like. But I believe the Pont du Gard -’

‘My dear, I’ve seen the Holborn Viaduct. Life can hold no more . . .’

I chose a restaurant for lunch because it had an elevated view of the river and St Paul’s – and, yes, there was the needle spire of St Bride’s Church from the film. On my way back I stopped at a former telephone exchange and noted the phone-like decorations on the front.

‘This music crept by me upon the waters’

And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street.

O City city, I can sometimes hear

Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street,

The pleasant whining of a mandoline

And a clatter and a chatter from within

Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls

Of Magnus Martyr hold

Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.

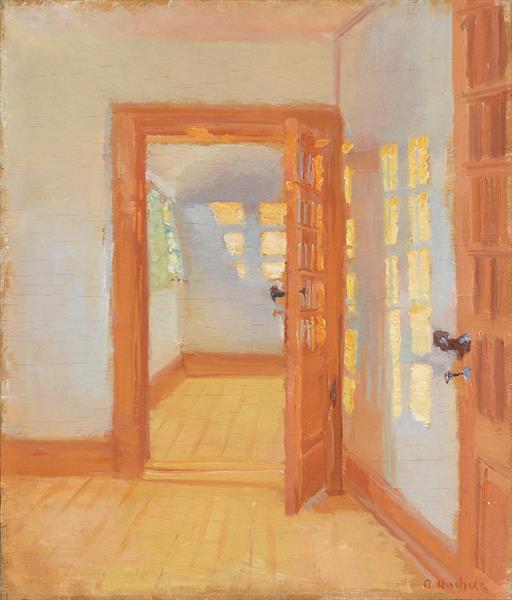

None of this was the aim of my day: I was going to Dulwich Picture Gallery for an exhibition on Anna Ancher (1859-1935), a Danish artist from Skagen, right on the northern tip of Denmark. Skagen was something of an artists’ colony, but Ancher was born and lived there all her life. She was admired for the way she painted light – and, certainly, some of her paintings were utterly delightful. It wasn’t just the depiction of light but also the colours.

My head was buzzing with other images by other artists, and once I had spent time with Ancher’s paintings I sat down and tried to separate them out. The little girl made me think of Philip Connard in Southport; the doorway of Gwen John’s corners of rooms (although more vibrant); there was something of Vermeer – and almost something of Rembrandt in an early portrait. There was something of the Glasgow Boys too, but with more sunshine. She painted local and domestic scenes of people she knew: her travels were to study other artists.

An enjoyable day all round.