It was an unlovely walk along Burmantofts Road to the museum; grey skies, damp cold, traffic, uninspiring housing, the absence of “theology and geometry” (I’ve just finished reading A Confederacy of Dunces) all conspired against optimism. But, really, it was nothing compared to what I was about to see of life in 19th-century Leeds.

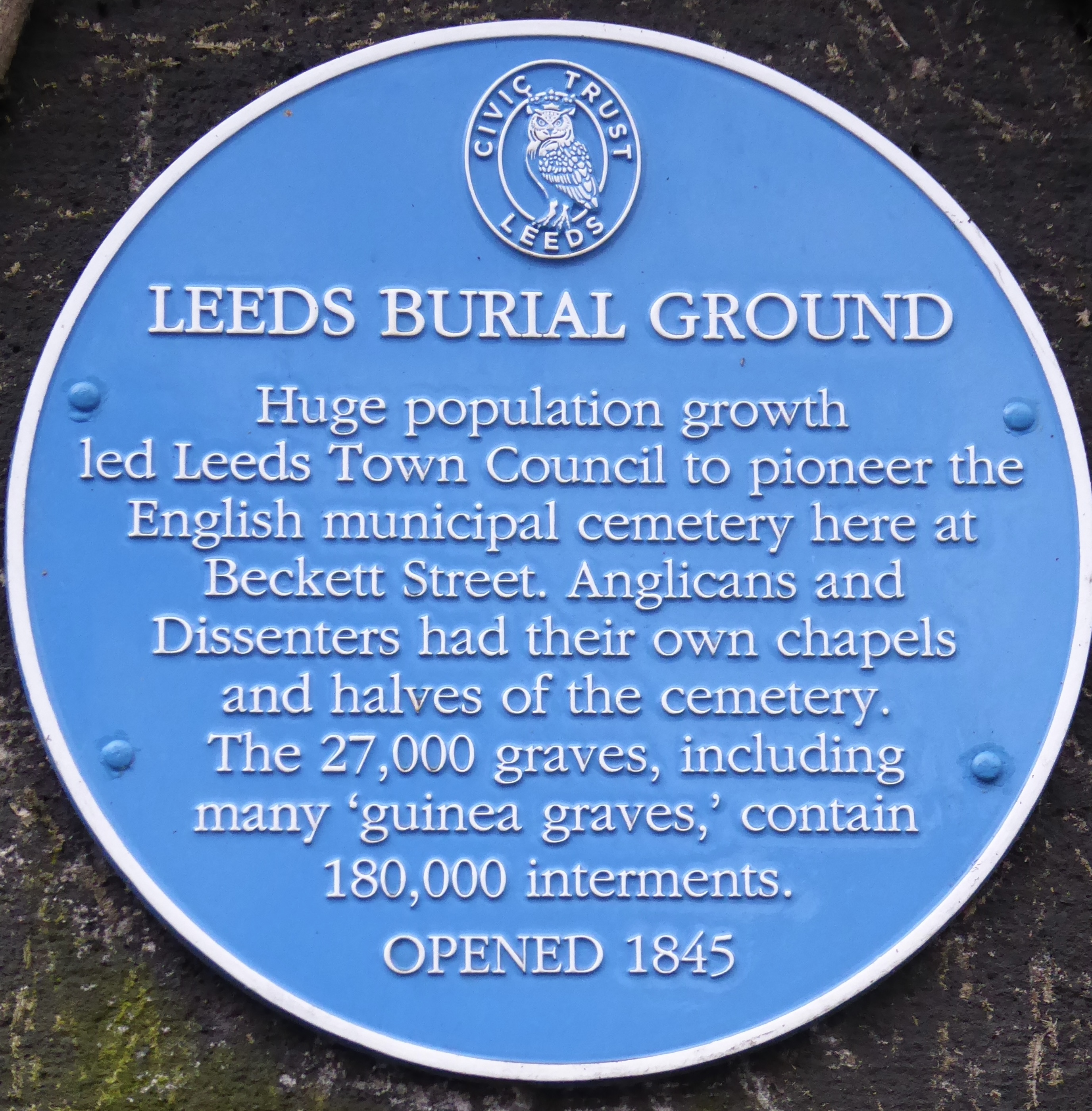

What is now the museum was originally built as a workhouse (1858) then later became a hospital. It’s imposing and ornate – lots of Dutch gables and Burmantofts tiles – but the thing that struck me at first was how BIG it is. It was built for 800 people; I don’t know how much misery and mental distress they experienced here, but living directly opposite the Leeds burial ground (27,000 graves with 180,000 interments) can’t have helped. Perhaps it was preferable to what had gone before or life outside – particularly when “life outside” in Leeds before the passing of 1848 Public Health Act seemed utterly revolting. (Edwin Chadwick as a benevolent social reformer or a centralising bureaucrat with a purely utilitarian approach to the health of the working population? Did it matter?)

The reason I went was to see the Lorina Bulwer scroll (1904). In her fifties she was put in the lunatic ward of the Great Yarmouth workhouse, where she embroidered this. But there was so – too! – much more to take in. I started off with Disease Street and began contemplating what it must be like to live cheek by jowl with no sewerage system or rubbish disposal and polluted air. With, perhaps, a meat market/abattoir at the end of the road. Public health measures brought disease reduction in their wake. Then the treatment of diseases and illnesses, the adoption of a more scientific approach (germ theory rather than divine punishment) but still contending with deep-rooted ignorance (poor Semmelweis). Medical advances: I had forgotten that Fanny Burney underwent a mastectomy without anaesthetic, and I finally understand how an iron lung worked (although it still looks like an instrument of torture). I still have a soft spot for the unscientific, though: the doctrine of signatures, leech jars, the lovely apothecary jars, the four humours (blood, phlegm, black bile, yellow bile).

On my way back along I stopped to photograph a pointlessly polite sign and its self-important initial caps.