Director Brady Corbet with Adrien Brody, Guy Pearce, Felicity Jones

“Overblown” is, for me, the only description. The final words of the film – “it’s the destination, not the journey” – were so bombastic that, like one last blow of its own trumpet, they widened the existing fractures and the whole edifice came tumbling down. (Unless it was some meta-joke, welcoming the viewer – at last! – to the end credits.)

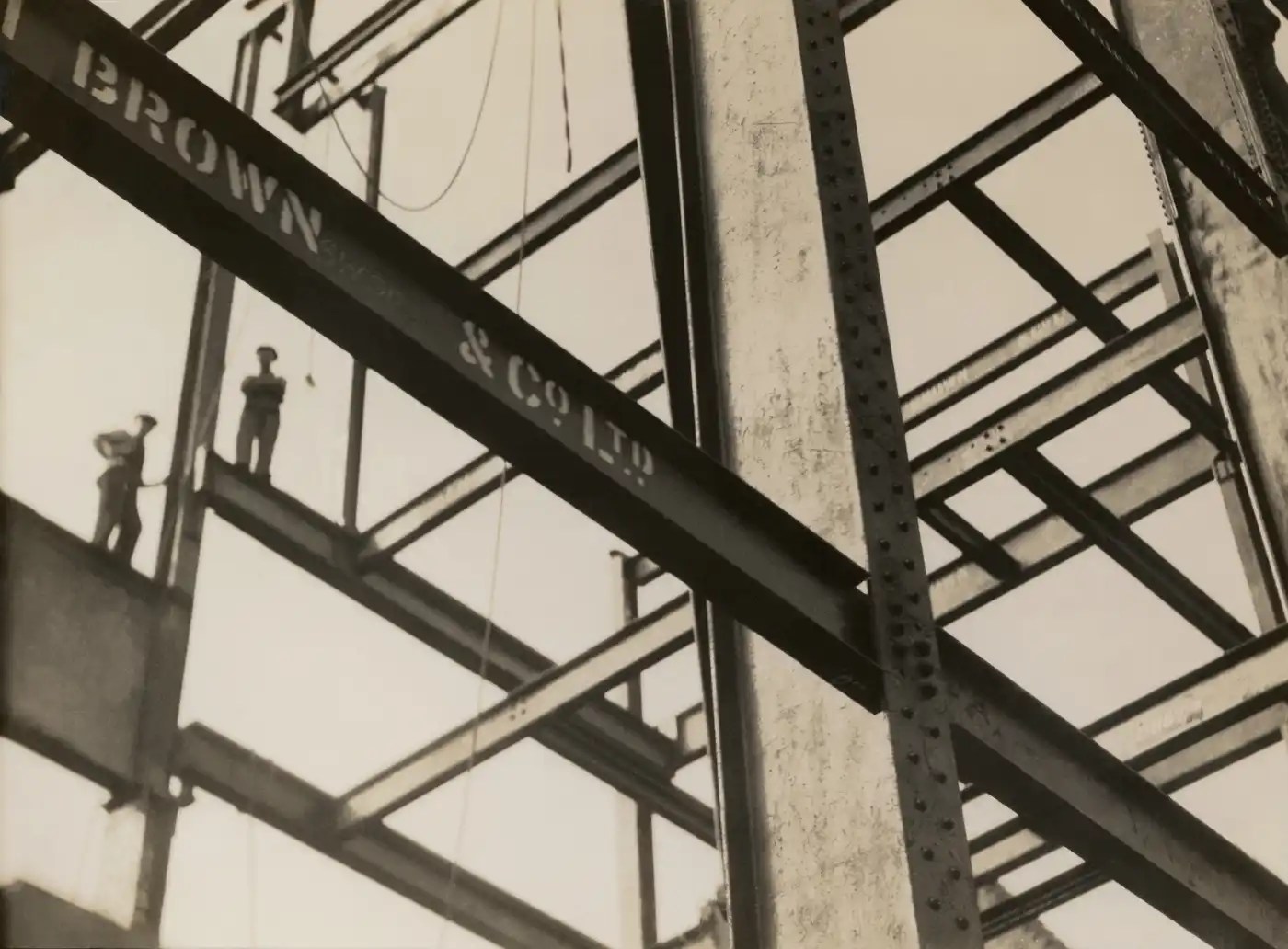

It started off well: Hungarian-Jewish architect is released from a concentration camp and sponsored by his cousin to move to a new life in Philadelphia. Fairly menial work for a long time until he is taken on by a rich, obnoxious-beneath-the-veneer man who has a grandiose scheme of his own. Eventually – after several years apart – the architect’s wife and niece are able to join him from behind the Iron Curtain. Things like that really made you feel the duration of post-war suffering for people already damaged by the war. The images were wonderful and striking, the acting was great, and I was hooked until the interval.

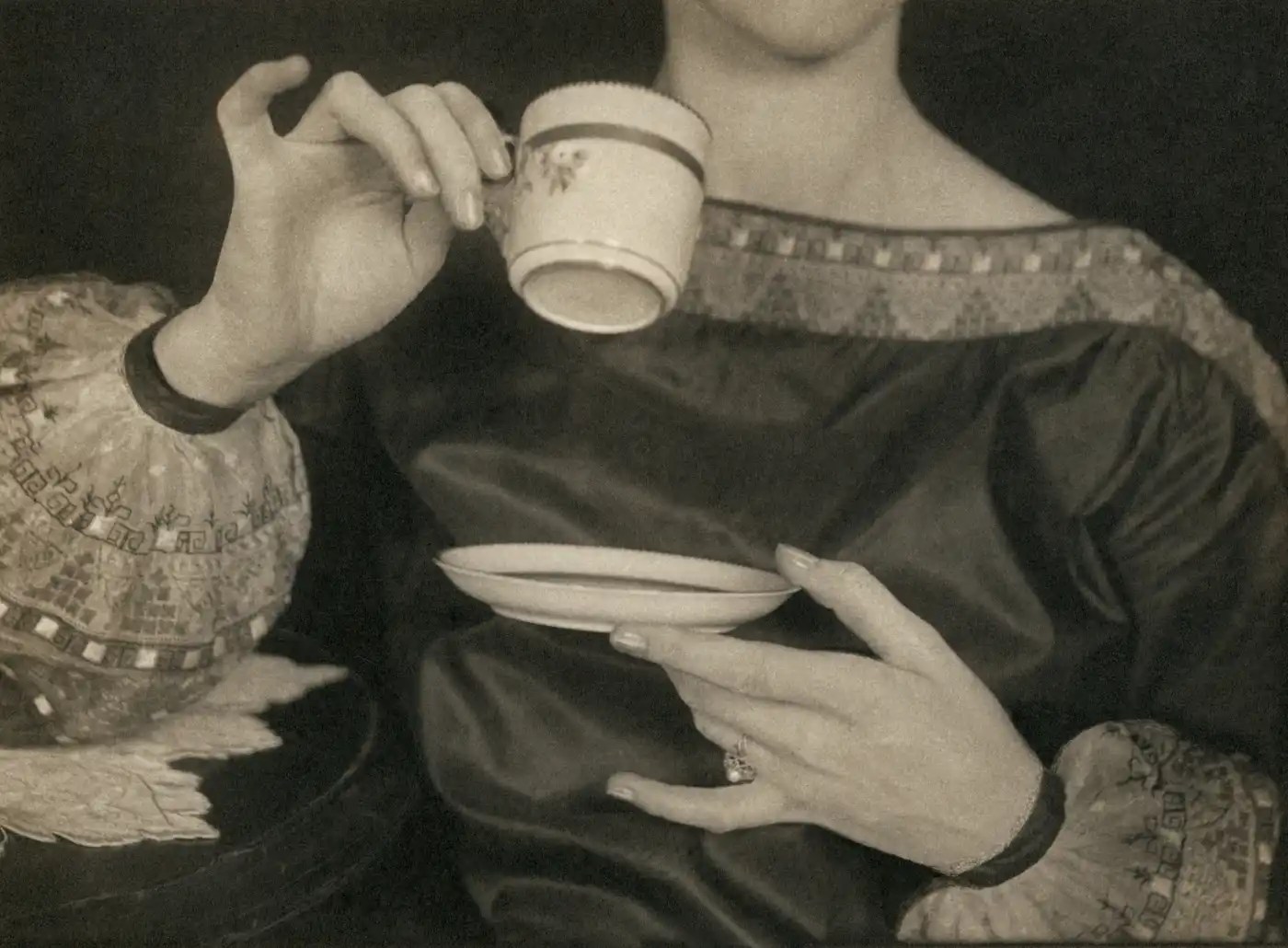

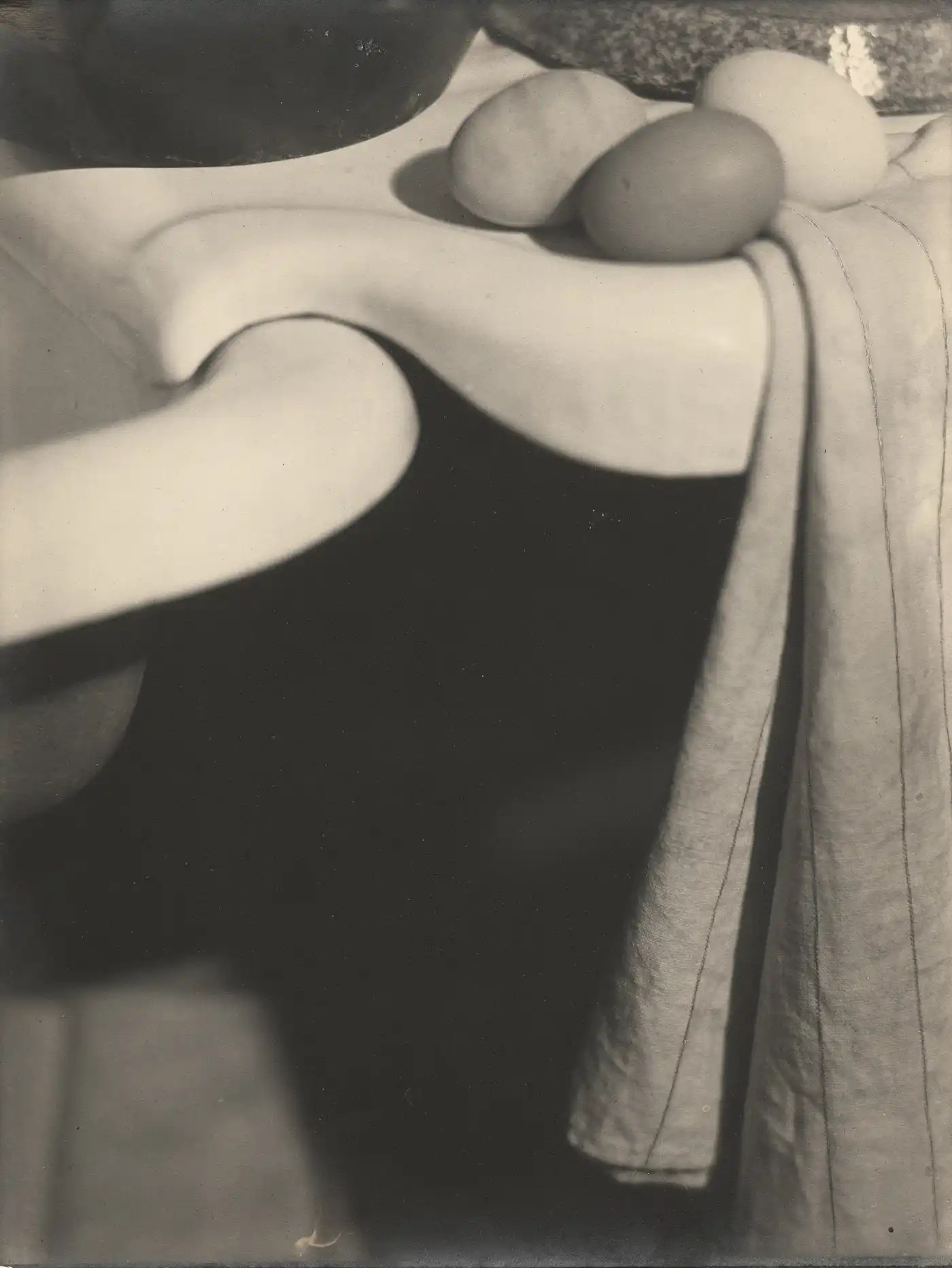

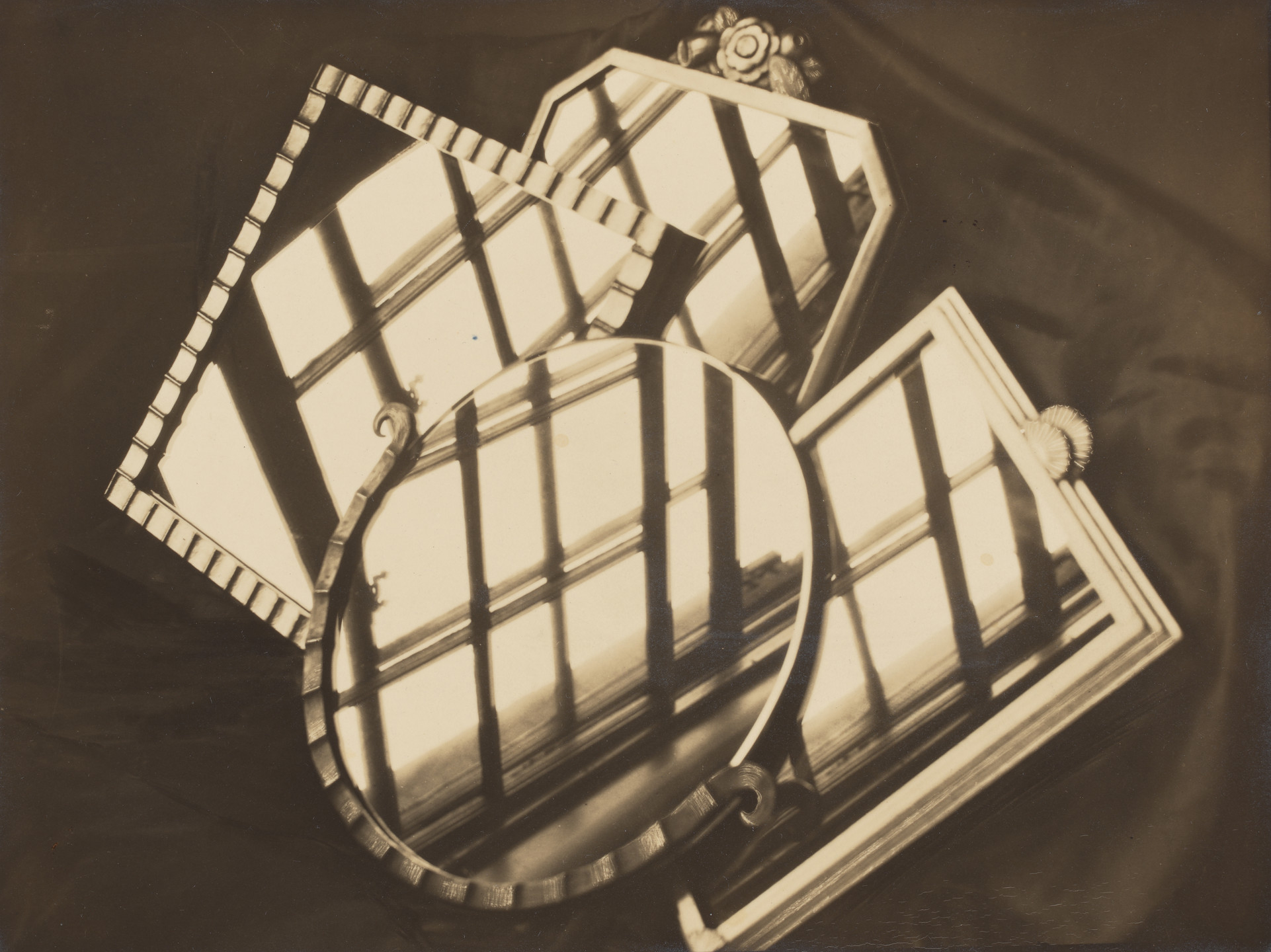

After that, too much was piled on. As a film about the building of the New Jerusalem (whether metaphorical or the founding of the state of Israel) and the Jewish experience in a new country that still despised you as the old one had – yes. Overweening ambition à la Citizen Kane – not so much. An architect driven by beauty, proportion and space – well, OK, but it’s a bit of a tortured genius cliché. The seductiveness of the vast wealth of the post-war US was tangible and woozily shot, but that look of beauty stretched to everything. The doss house, shovelling coal, life in a wheelchair – all beautifully framed and shot. (The 1980 epilogue really looked a documentary film from the 1980s. Technically brilliant.) That started to grate. How many more shots of the sunlit cross on the altar did we need? The years in a concentration camp were almost irrelevant until the end, when it was revealed – far too late – that the size of camp cells had been the inspiration for designs. If you’re going to focus on boxy and enclosed spaces for over three hours, give the audience a clue a bit earlier on. And – excuse me – born in 1911, studied at Dessau and a celebrated architect before the war? That’s stretching it a bit.

But all the reviewers think it’s wonderful.