The usual 30km ride from the ferry to Rotterdam Centraal – into a headwind, which is just unfair. I’m more familiar with that ride now that routes around my own neck of the woods. Then trains to Amersfoort and then Osnabrück. I just ask people to help me get my bicycle and panniers onto the high trains.

The list of things that can go wrong has grown. Last-minute platform changes I am used to (there was one at Leeds yesterday that set me running), but today I was introduced to the sense of ignorant helplessness you feel when everybody else knows what is going on because they are on the app and act as one – leaving me stranded. We were all waiting on platform 14 when, like a shoal of fish, everyone turned and started flowing down the escalator. No announcement – just a hive-mind connected by the app. Someone said “twaalf” to me, so I dashed to platform 12. There was a train – still no announcement – and I stood by the door with the bicycle symbol. Another mass flow – the train was only the front half.

Anyway I got to Amersfoort – and discovered that I was in time to catch the much-delayed Berlin train that calls at Osnabrück. I had a flexible ticket so that was OK, but I didn’t have a bicycle reservation for that particular train. Since my bicycle was the only one in the racks, I don’t think I inconvenienced anyone.

Upshot: on a day of train traumas, I got to Osnabrück an hour earlier than expected.

But the real depth charge to hit my holiday is today’s announcement that there are strikes on some Dutch trains from tomorrow. I’d already factored in Sunday’s closure of Osnabrück station to remove a bomb (if I’ve translated correctly) and its impact on my vague plans, but the thought of Dutch trains being unreliable when I was relying on them to carry me across the country on Monday is too much. So farewell Bremen and the Geestradweg. I shall be just be pedalling west into a headwind for the next few days.

And making the best of it.

Well, it’s not like I didn’t know the risk:

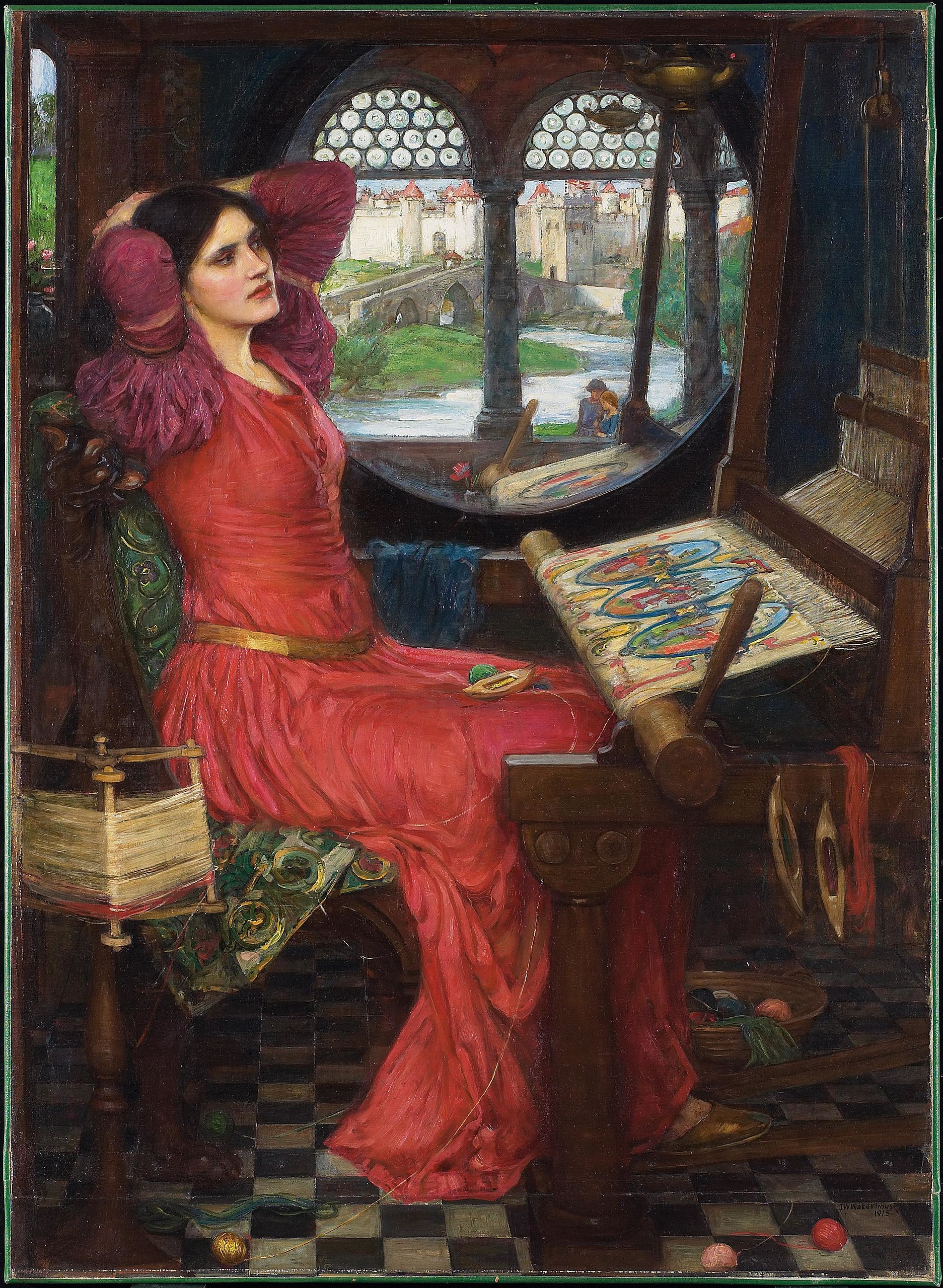

Tout le malheur des hommes vient d’une seule chose, qui est de ne savoir pas demeurer en repos dans une chambre