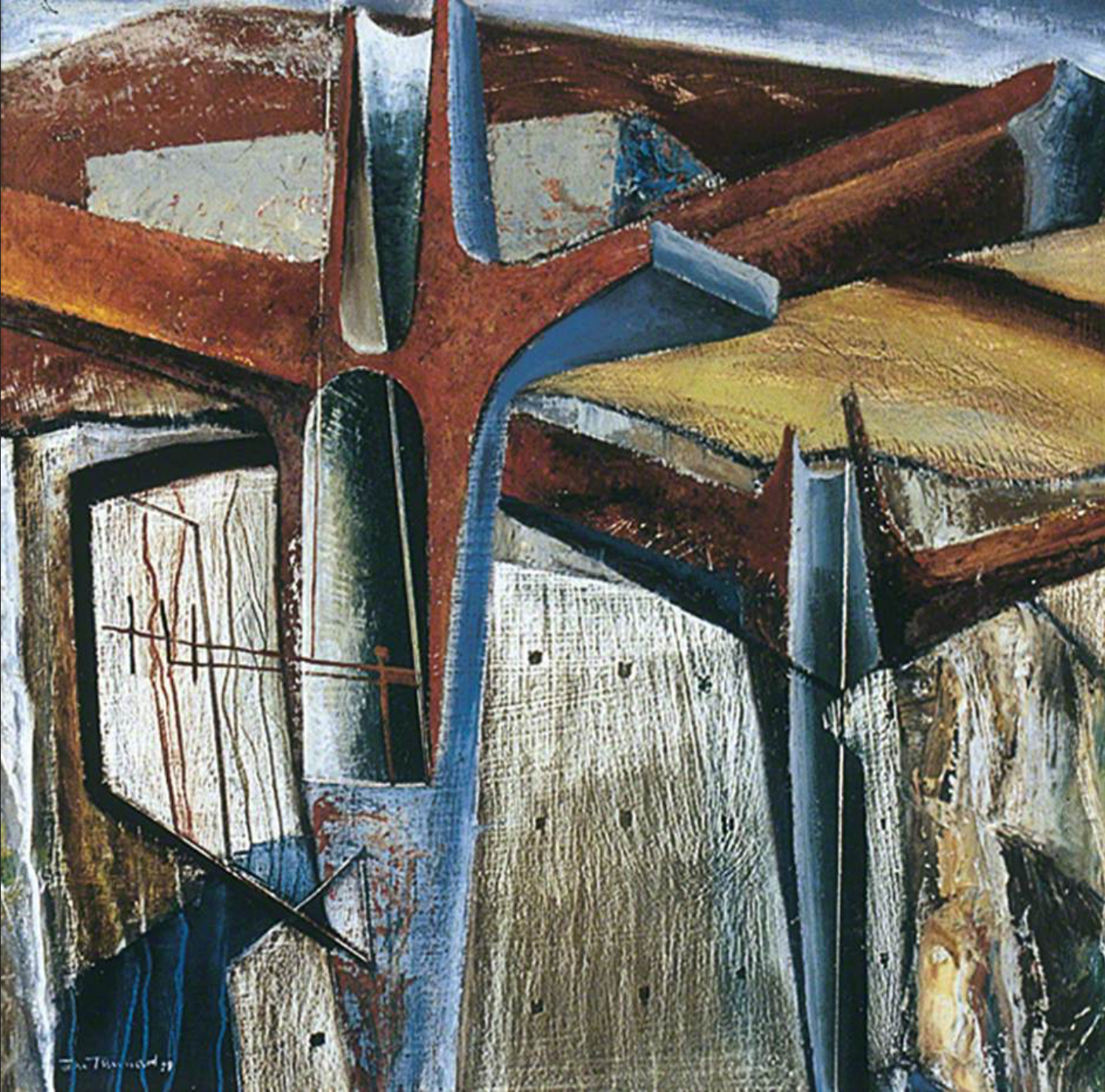

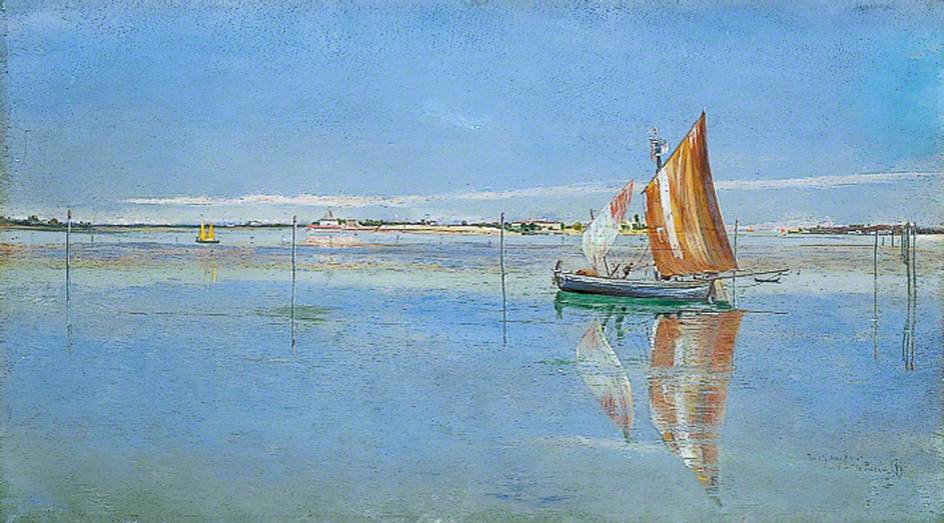

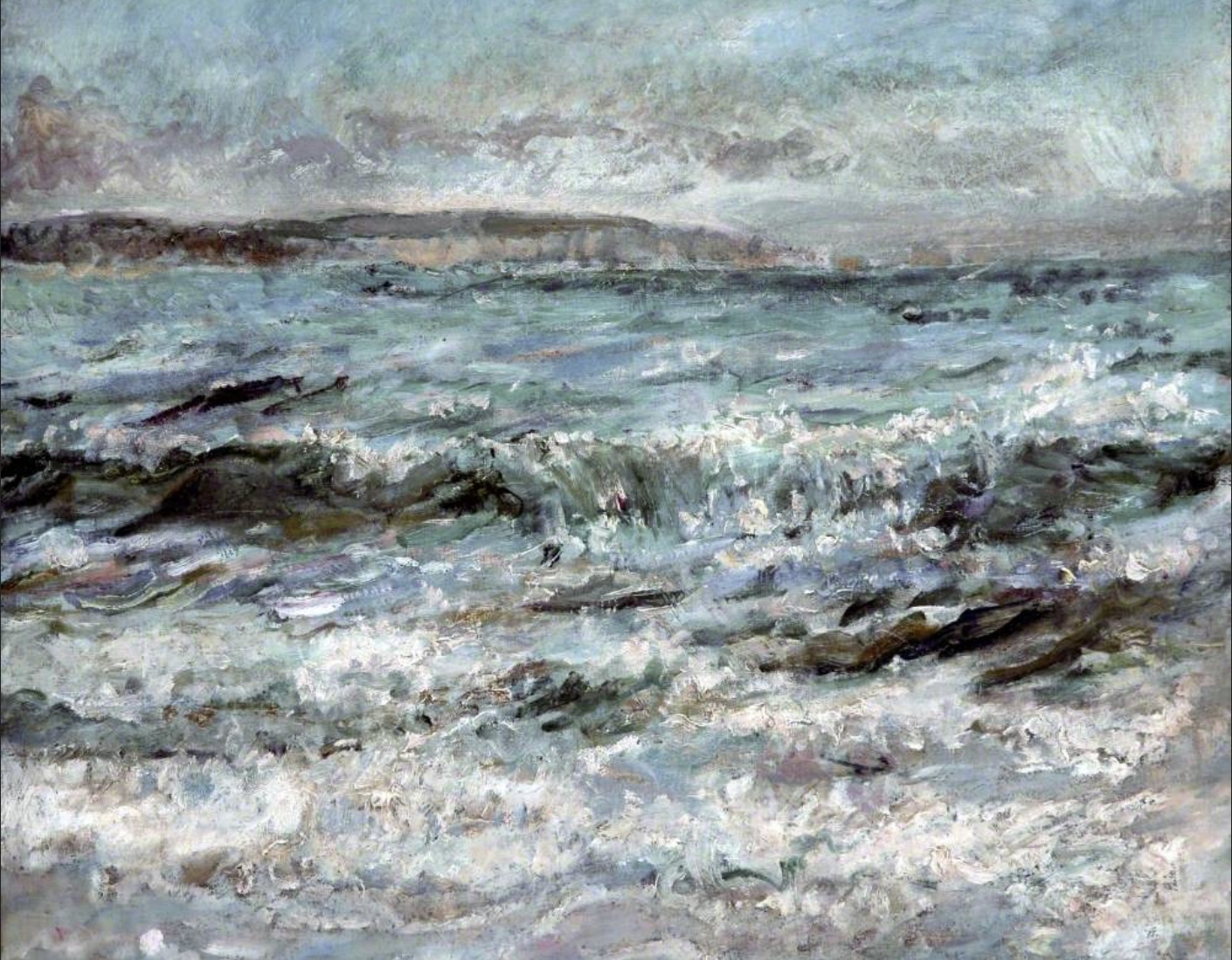

I went to see the “Turner: Always Contemporary” exhibition at the Walker, which was very good. Liverpool’s Turners have been brought together and exhibited with later 19th century and modern artists. The modern art link was a bit hit and miss; I smiled as the gallery attendant regularly asked people to stay outside the floor-taped cordon sanitaire around Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde-encased “Two Similar Swimming Forms in Endless Motion” as if she were part of some performance art. What was more interesting was comparing Turner to water scenes by Monet, Courbet and Ethel Walker. Their pictures seemed so lifeless and stilted beside Turner; somehow the mistiness of his work kept the images in motion as they came in and out of focus. I don’t think it was just a matter of fewer straight lines.

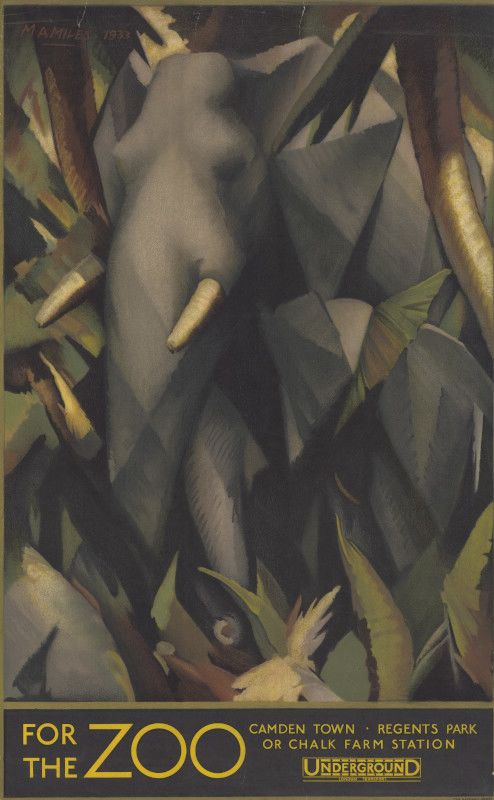

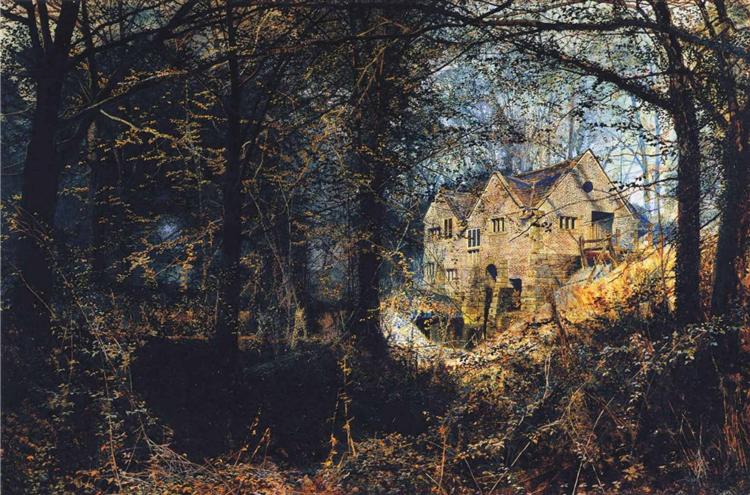

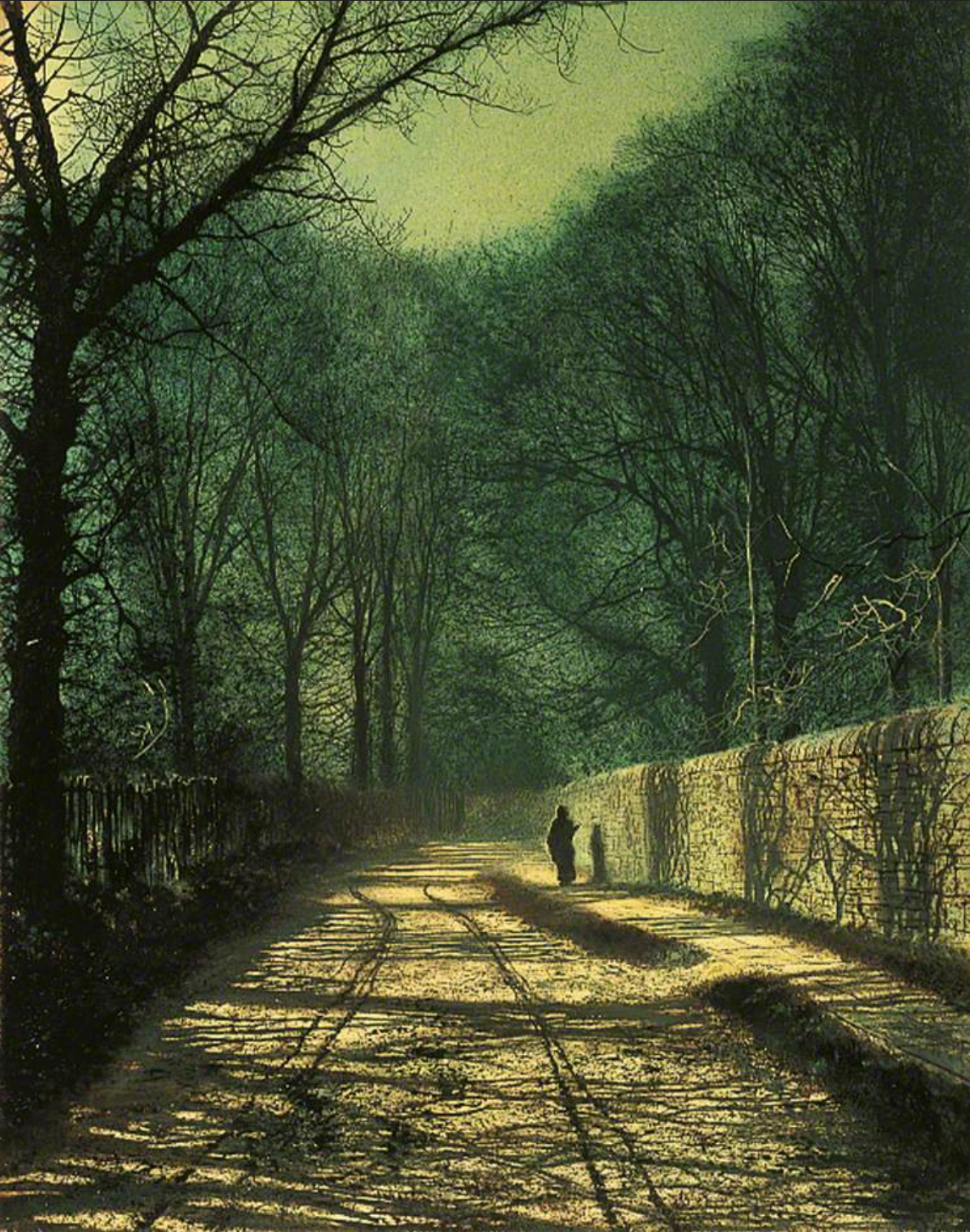

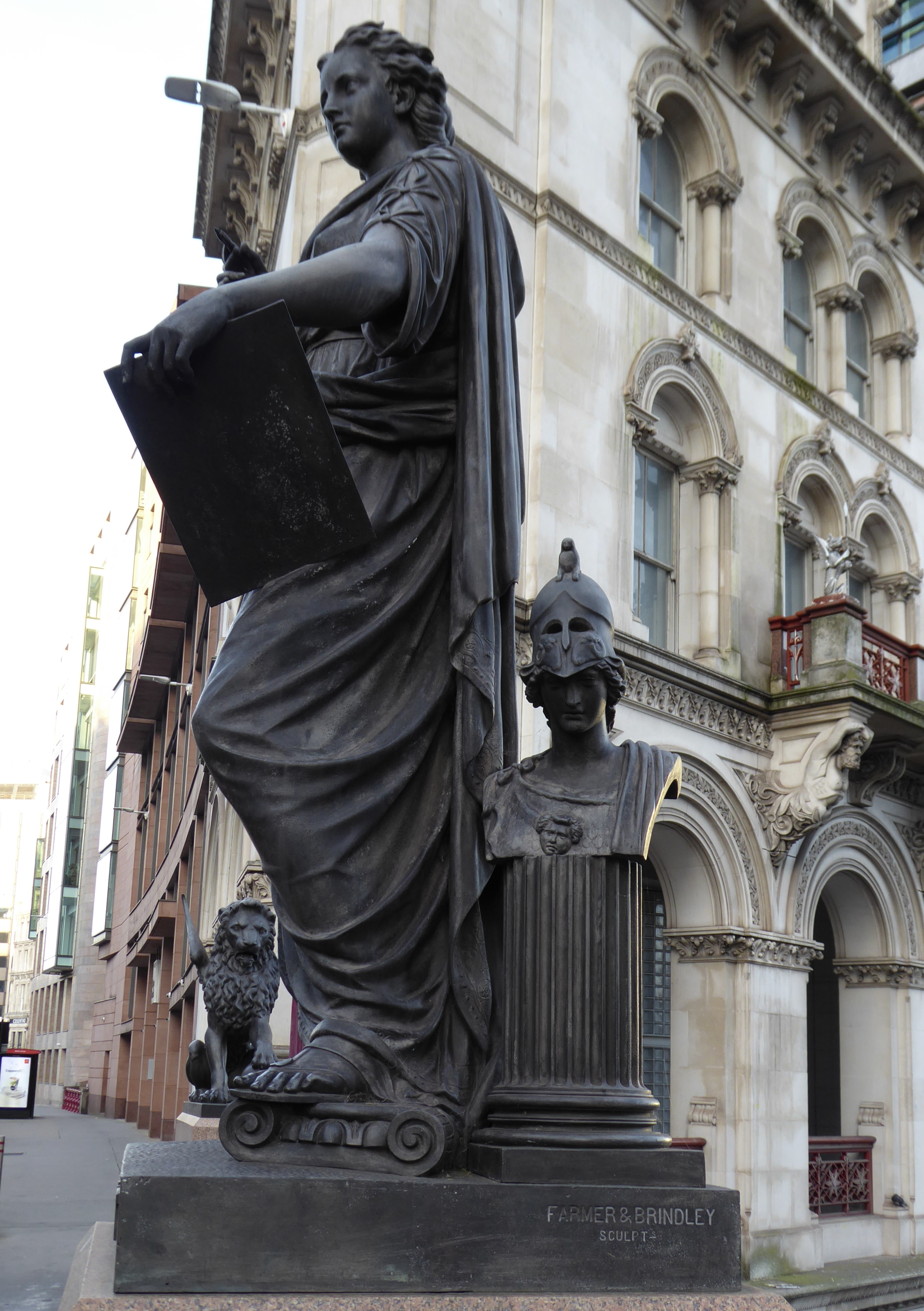

Serendipity: amongst the non-Turner paintings was one of Dordrecht, which reminded me of waterbus journeys to Rotterdam. (Turner learned from older paintings.) You could follow his move from representational landscapes (albeit ones where features were re-arranged for greater artistic impact), through his “mass” prints in the Liber Studiorum (some of which I saw in Manchester) to his later quasi-abstract paintings. J Atkinson Grimshaw also secured a spot with his paintings of Liverpool’s Custom House on the front; they are indeed wonderful, and you can see the build-up of paint in the foreground like mud on the cobbles.

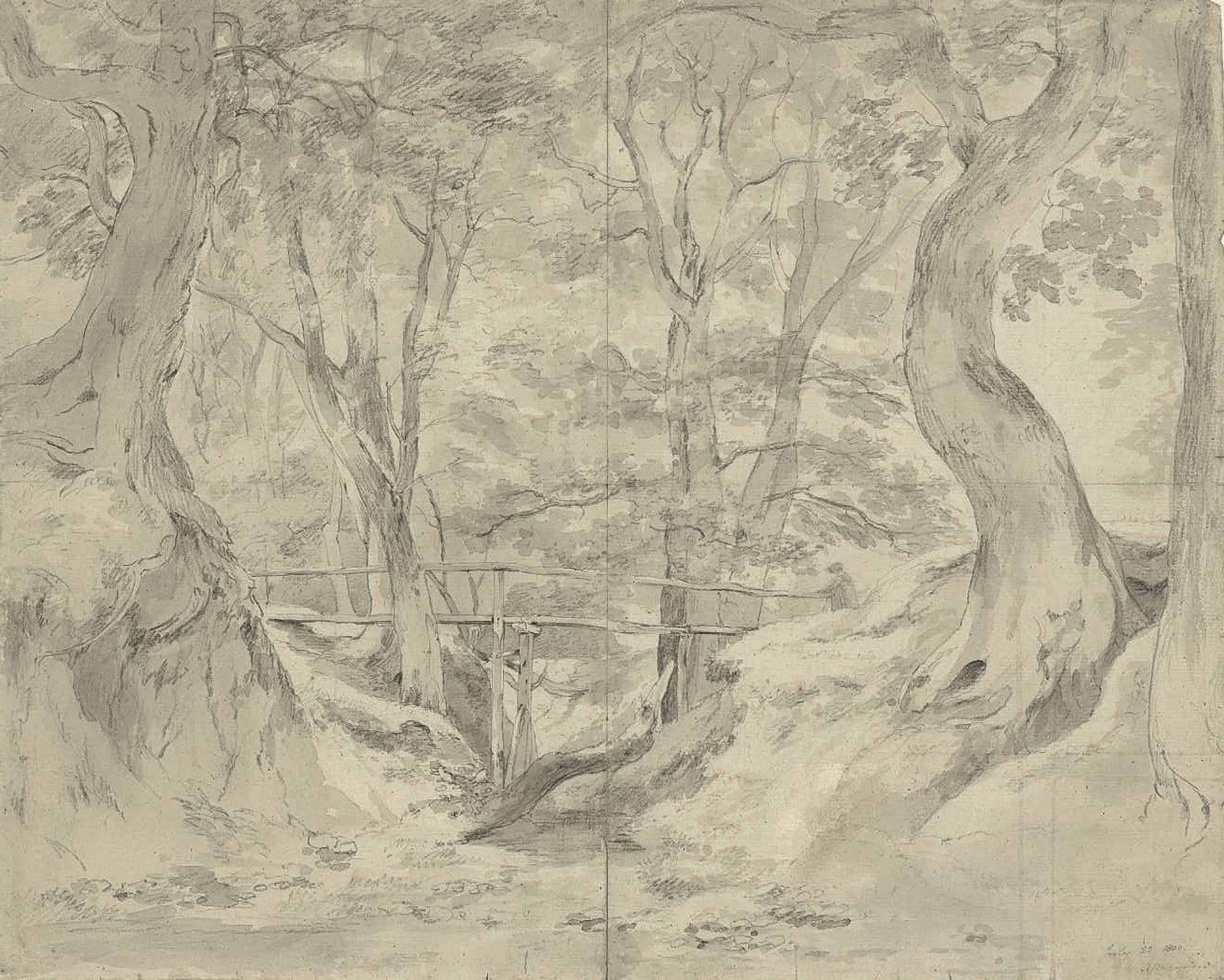

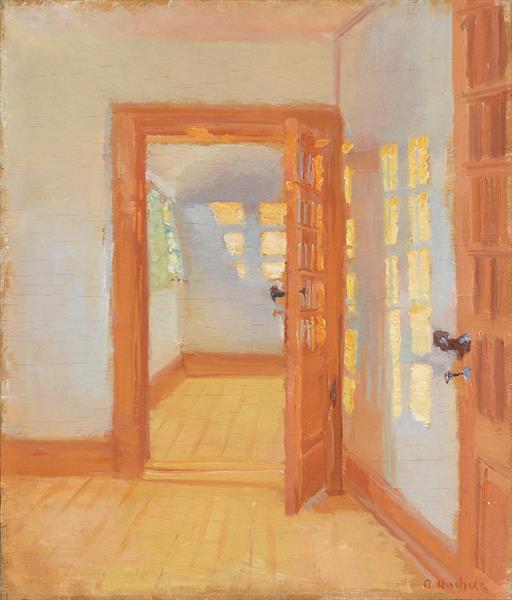

Then I wandered around the rest of the Walker, venturing into galleries I barely recall visiting before. Elizabeth I by Hilliard, comparisons of Flemish and Italian Madonnas, a Rembrandt, wall after wonderful wall of 18th-century ladies and gentlemen that I didn’t have the headspace to look at individually, a Nocturne by Marchand, a view of Berne by a follower of Turner (I wonder why he didn’t make the exhibition?), and a horse painting that looked like one I had seen before.

Other things before I forget: a 1783 ceramic dish with a painting of a slaving ship, “Success to the Will”, was referenced in a modern work, “English Family China”, from 1998. They are cast from real skulls (never have the words “bone china” sounded so sinister) and implicitly comment on the link between wealth and horror. There was a painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, which, unsurprisingly, made neither the National Gallery nor this exhibition. I gazed at a lovely 15th-century Book of Hours and clocked another Beuckelaer. He must have churned them out.

The Christmas market was set up in the square outside and I contemplated a ride on the big wheel – but it was raining steadily and there was no inviting movement from the wheel, so I headed off for lunch instead.

Then the Museum of Liverpool for an exhibition on treasure unearthed in Wales and the north west of England. (A magnifying glass would have been useful.) Some of it was indeed treasure – gold or silver – but some had little value even at the time. The third-century Agden Hoard, for example – c 2,500 Roman copper alloy coins (“radiates”) from a time when galloping inflation made them almost worthless. There was also the golden Mold cape, which I have seen at the British Museum.

The sky was brighter as I left, but the big wheel was still static so I caught my train instead.