Not much point in borrowing a big book on politics and not trying to remember something of what I have read!

But first: what type of big book on politics? I borrowed two: one (1967) on the essential writings of Karl Marx, and another, “The Politics Book” (2024). The difference in presentation was quite something. I couldn’t face the dense text and the unknown concepts of the first so stuck with the picture book. (It’s not like I wanted to know everything – just a bit more than I already did up to the start of the twentieth century.) The picture book focused on thinkers to present different political approaches/ideologies. I’m not sure how some of them made the cut: Nietzsche but not Napoleon. There are vast gulfs too in many of the stances: Gandhi (“Non-violence is the first article of my faith.”) or Mao (“Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”).

It’s been interesting to see the proliferation and increasing complexity of ideas over the centuries, responding to industrialisation, colonialism, increasing secularisation, the idea of universal rights – not to mention revolutions and wars of independence, and of the rising importance of economic maintenance. Also different emphases – on whether human nature is predominantly self-interested or co-operative; nation state or federation; political moralism, realism or pragmatism?

Confucianism – rule by benevolent, wise king supported by loyal ministers who advise him and have the interests of his subjects at heart. A moral king sets a good example, which will filter down to the populace. Hierarchy is flexible – ministerial positions open to those of ability and good character. Reciprocity in relationships. Confucius lived mid-6th century BCE, at the end of the peaceful Spring and Autumn period, and his vision of how to administer an empire was more suited to peacetime than the Warring States period (476-221 BCE). Legalism – authoritarian and pragmatic – prevailed until the establishment of the new empire under the Han dynasty, when Confucianism was adopted as the state philosophy.

Sun Tzu – contemporaneous with Confucius – and The Art of War. The importance of maintaining strong defences and strategic alliances. The leader as a moral example who can command loyalty. War as a last resort.

Plato and the Republic – 5th-century Athens. The art of living well/virtuously (eudaimonia) is only fully understood by philosophers: politicians are interested in wealth and power and at best only imitate virtue, whereas a philosopher has studied and truly understands a virtuous/good life. If you can’t make a philosopher king, then you must make the king a philosopher.

Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Focus on empirical evidence rather than the intellectual reasoning of Plato. Man is a social animal; it is unnatural for him not to live in a polis. The polis or state exists to enable men to lead a good/virtuous life, and the form of government affects this aim. Three forms of government and their “corrupt” versions: monarchy/tyranny (i.e. defective monarchy); aristocracy/oligarchy and polity/democracy. Aristotle favoured polity – the rule by many for the benefit of all – over democracy. His works – more lecture notes than books – barely featured in western Europe between 600 and 1100 and were better known in the Arabic and Byzantine worlds. Thereafter his works were translated into Latin from Greek and Arabic and more widely read.

The Roman republic spread power through a mixed constitution – Consuls, Senate, popular assembly – which provided checks and balances until it was replaced by the empire (and its succession of ever-more-bizarre rulers).

Monotheistic religions, once they gained power, introduced the divine into politics. Augustine of Hippo and the division between civitas Dei and civitas terrea, and the concept of the just war. Muhammad, while extolling peace, spread Islam through conquest. Al-Farabi (c 900) was influenced by Plato, but replaced his philosopher king with a philosopher prophet/a just imam. The Virtuous City however remains a myth: citizens prefer earthly pleasures and reject a virtuous ruler.

Thomas Aquinas (13th century) married Christianity and Aristotelian logic: human reason can provide arguments for the existence of God. His political insight was that a war is just if it has a just cause and is conducted in accordance with reasoned notions of justice. “Natural law” is inherent, determined by reason, and aligns with God’s law; “human laws” are those rationally-based ones that we apply to ensure the smooth running of society.

Marsilius of Padua (1275-1343) – writing at a time of one of those power struggles between the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor – stated that the Church – i.e. the papacy – should not have political power. An early version of secularism.

I was rather taken with Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), who seems to argue from observation rather than theory. “Government prevents injustice, other than such that it commits itself”. He acknowledged the dynamism of government: it begins with natural social cohesion, then expands into government for the well-being of the governed, but morphs into the domination of the ruling class and the exploitation of the governed.

And so we come to Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) with his espousal of pragmatism and ditching of any religious ideals. Human beings are a malleable bunch: we are self-centred and fickle, but we are also imitative and can be persuaded to act benevolently and co-operatively under an effective leader. Social organisation is key; the ruler’s morality is secondary to state security and utility. Political life is a constant battle, and its weapons are secrecy, intrigue and deceit. (No wonder Machiavelli has a bad press, but he did not condone these methods in private life.) This approach applies where there is a sole ruler – a monarch or “The Prince” of Machiavelli’s treatise – but a republic (perhaps introduced by exactly that deceit and intrigue that he condoned) would operate differently. At this point it’s worth noting the turbulent times that Machiavelli lived through. Peace and stability at any price might have been worth it.

Europeans’ brutal exploitation of the Americas and criticism by the School of Salamanca. Francisco di Vitoria (first half of the 16th century) stressed the principle of natural law: we all share the same nature and therefore have the same rights. Religion was not a just cause for war. Francisco Suarez (second half of 16C) – sorted laws into natural, divine and human; no human-made law (positive law) should override people’s natural rights to life and liberty.

This move away from divine or natural law towards individual liberty and rights was extended by Hugo Grotius (1583-1645): people have rights to life and property and the state has no right to take them away.

Consociation: Johannes Althusius (1557-1637), Calvinist political philosopher. Human communities come into being through a kind of social contract. Like Aristotle, Althusius stressed the sociability of humans. Individual communities are subservient to the state, but collectively they are superior to the state. Federalism, but one that is less individual-based than in the present day.

Sidelining of ideas of divine law with the rise of the modern scientific method and empiricism; greater stress on the idea of human nature untethered from social structures. How did people actually behave? Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679 – so he lived through the English Civil War) and his pessimistic view of human nature. Without strong government, people would live in a state of perpetual wrangling, each individual self-interested and anarchic (the “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” scenario). Therefore strong government is essential, and individuals submit to it under a form of social contract for the sake of the safety and rule of law that it promises. The sovereign is absolute so long as he guarantees the safety of the people.

John Locke (1632-1704): liberalism. Continued the idea of the social contract, but government should have a limited role. Its task is to protect citizens’ rights to life, freedom and property, and Locke held it acceptable to rebel against illegitimate government.

Montesquieu (1689-1755) argued for separation of powers: an executive branch for enforcing law, a legislative branch for passing and amending laws, and a judicial branch for interpreting laws. This would avoid despotism and create a stable government; the idea became influential in the creation of the United States constitution (1787) and in France after the revolution.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Unlike Hobbes, Rousseau believed that, free of state control, man in a state of nature, is actually a happy and contented creature. The social contract trammels him, but government is not set in stone. Under a new type of social contract man could be free and content again within the bounds of new laws and a society could even become perfectible. Sovereignty comes from the people (the general will), not the ruler – via popular assemblies, though, rather than modern democracy.

Edmund Burke (1729-1797) anti-Rousseau and a Whig, he favoured gradual progress in society, not an abrupt break – e.g. the French Revolution, whose outcome horrified him, whereas the 1688 “Glorious Revolution” was acceptable because it restored order to the country. He was also in favour of American independence. He thought that discussion of abstract rights distracted from the job of government, which is to administer the country. Passions of the individual should be subjected to the laws of the country to ensure the fairest outcome.

Thomas Paine (1739-1809) was one of the first to propose democracy in the form of universal male suffrage with no property qualification. Highly critical of the corruption and inadequacy of the British Parliament of that time. Voting is the way for society to shape a government that reflects social needs. Monarchy and other hereditary principles are unnatural. and can lead to despotism. Like Burke (once his friend), Paine was a strong supporter of the rights of American colonists to independence – but also of the French revolution. (He avoided execution there.) He followed Rousseau’s idea that the general will of the people should be sovereign in a nation and believed that, with fair elections, private interests and corrupt practices would wither away. Reflected in the American Declaration of Independence and its insistence on inalienable rights.

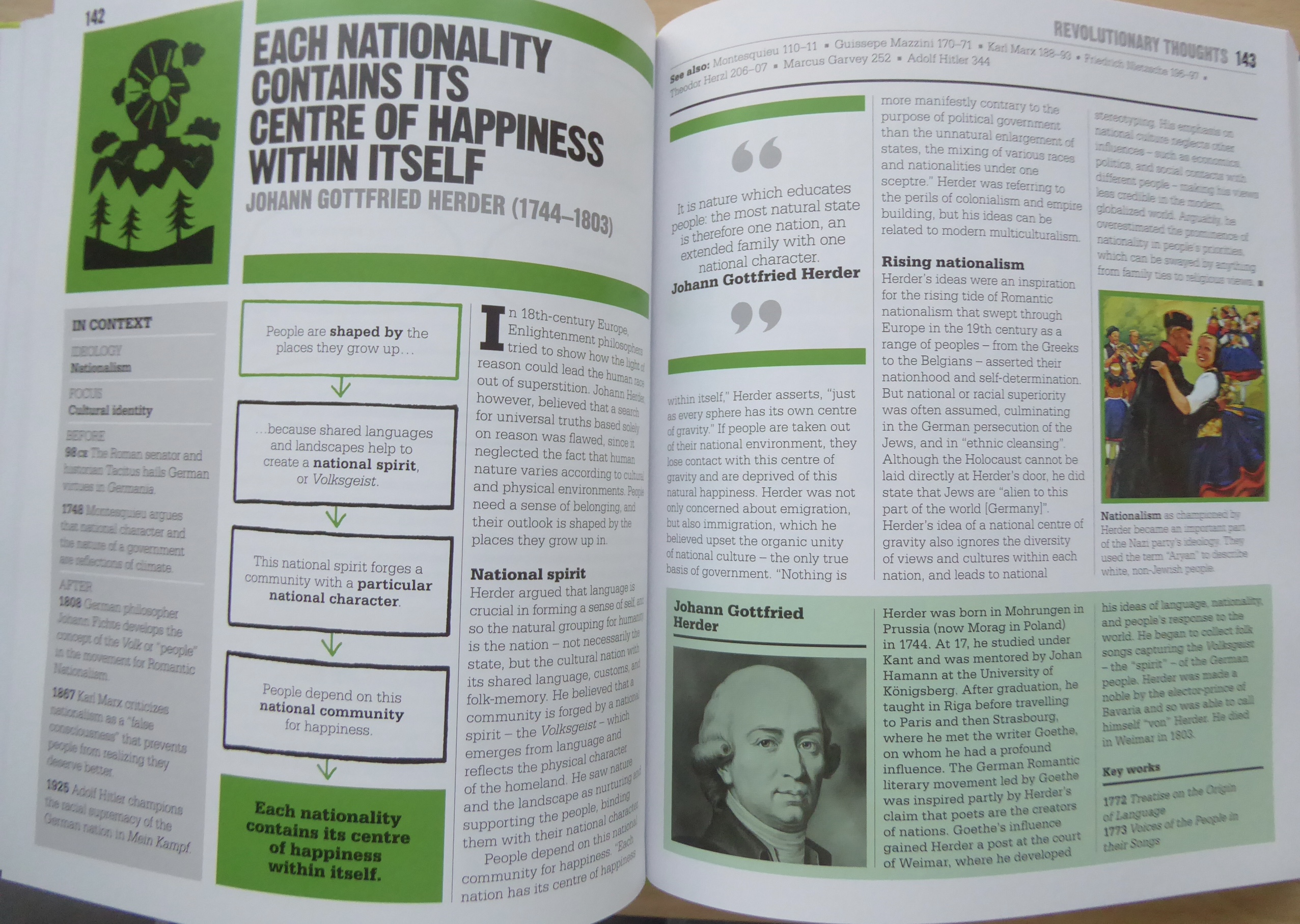

Enlightenment thought with its emphasis on reason was challenged by Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), who held that a person’s shared cultural and linguistic background shapes character. A cultural nation with its own Volksgeist was where man was happiest. His ideas were influential to the rise of Romanticism and the 19th-century development of new nation states (Belgium, Greece).

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and utilitarianism: the greatest good to the greatest number of people is the measure of right and wrong. A government’s task is to decide which laws are likely to produce more universal good than harm. Bentham devised the felicific calculus to work out this problem.

In favour of universal suffrage – not from the perspective of natural rights but as a pragmatic way of ensuring that only a government that increased general human happiness for the greatest number would triumph.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) – A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Without education, women cannot earn their own living. They are therefore dependent on men for financial support and must do what they can to catch a husband. Respectable women who do not play this game are eternally at a disadvantage.

Simón Bolívar (1783-1830) – rejecting power of the Spanish in South American countries. Small republics should replace colonies: a small republic is self-contained, has no reason to expand its boundaries and therefore is a stable and just state, whereas a monarchy or an empire is constantly trying to conquer other lands. Behind the liberation of Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, northern Peru and NW Brazil.

Carl von Klausewitz (1780-1831) – “war is a continuation of politik by other means”, by which he meant that war is a serious act of one state imposing itself on another and must have an overriding political goal.

Auguste Comte (1798-1857) – French positivist philosopher: understanding society requires valid data from the senses, followed by the logical analysis of this data. Society operates according to laws, just like the physical world of natural science, and the family – not the individual – is the true social unit. “Families become tribes and tribes become nations.

“

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) argued for a return to the ideals of the French Revolution. He wanted a democratic, free, classless France and rejected socialism. His saw socialism as promoting materialism, bypassing the highest human virtues, undermining the principle of private property (which he saw as vital to liberty), and stifling the individual.

The rise of the nation state in the 19th century. Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872). Individual rights and interests are not a good enough basis to govern a society. People need to work together within their country (created by God) as an association, a brotherhood, for the common good.

John Stuart Mill combined Bentham’s utilitarianism with individual liberty in liberalism. He thought that people should be free to think and act as they wish so long as they don’t harm anybody else.

The “tyranny of the majority” can bring conformity and stagnation; eccentricity was the mark of a dynamic society, where there would be a profusion of ideas that could be tested in the “bubbling cauldron” of public opinion.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) and the idea that “property is theft”. Rights to liberty, equality, and security were the basis of society, but the right to property was not in the same league. Property, in fact, undermined those rights because it enshrined liberty for the rich and perpetuated poverty for the poor.

Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876). The only authority to acknowledge is the laws of nature. They are the only constraints on us. We should rebel against the authorities of religion and government. Anarchism is the path to human freedom and human liberation.

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862). People – citizens – must do what their moral conscience tells them is right, even if it means rebelling against the government or engaging in civil disobedience. By being passive, citizens may find themselves colluding with injustices that they would otherwise condemn, like slavery.

Karl Marx (1818-1883) – his analysis of 19th century industrial capitalism and his theory that material and economic factors influence historical developments (the dialectic). His theory rested on its internal logic more than sociological observation (although there was Engels). Production of goods essential for human life can be organised in different ways; the way that they’re organised gives rise to different kinds of social and political arrangements. Man needs to work to provide himself with certain goods, but work also has the potential to be intensely fulfilling. Under the Victorian industrial capitalist system, though, workers are alienated from what they produce. Instead of creating the products that they themselves use, they create them partially and en masse for an employer for wages. Hence they sell their labour, which becomes just another commodity.

This alienates them from their true nature – creative, sociable – and from their fellow workers.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) developed Schopenhauer’s notion of will to survive as a “will to power” – a no-holds-barred striving to higher values. He presented this Übermensch as the successor to the deities of organised religion.

Georges Sorel (1847-1922) sounds a bit incoherent. Political structures in the 19th century were changing fast in the wake of industrialisation and population movements. Sorel believed that parliamentary democracy failed the working class and benefitted the middle class.

What the working class needs are myths to believe in, and violence is a way of actualising these myths. At first he supported syndicalism – the most militant wing of the trade union movement which favoured strikes over political manoeuvering – but by the end of his life he seems to have tasted just about any political theory

Eduard Bernstein (1850-1932) was a member of the German Social Democratic Party, which was guided by Marxism. Bernstein noticed that Marx’s predictions weren’t happening: workers were not moving towards revolution. In fact, they seemed to value the stability and security of capitalism. He therefore proposed ditching the idea of revolution and accept that socialists look at what workers actually believed and work on that – gradual rather than revolutionary socialism. (The Social Democratic Party formally renounced Marxism in 1959.)

(This is particularly relevant since I’m re reading this on the day that Trump has removed the Venezuelan president.) José Martí (1853-1895) Latin and South American countries had mostly thrown off European shackles, but Martí warned of colonialism of a new kind from the United States. The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 affirmed that the United States remained opposed to European colonialism, but it also identified both North and South America as falling under the “protection” of the United States.

Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921) and anarcho-communism. He argued that the best aspect of humanity is its ability to co-operate; this would allow it to do away with all oppressive structures; a new society could be based on mutual respect and collaboration.

Sun Yat-Sen (1866-1925), Chinese nationalist, hostile to the weak and corrupt imperial court. He stressed the strength of Chinese culture and wanted to fuse China’s traditions with “Western” development. He laid down the Three Principles of the People: nationalism, democracy and people’s economic improvement on the basis of fair distribution of China’s resources

. The Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911 and Sun was briefly president in the new Republic of China.

There’s also the whole history of twentieth-century decolonisation and newly independent states which I’m trying to get my head round. Not just the new political structures but also the absence of a contemporary home-grown model of government.

And the point we are at now? A global plate-spinning exercise. On the one hand powerful elites – business, military, key politicians – run the institutions which provide us with what we expect in our prosperous western world. It’s hard to see how they can be reformed without serious economic consequences. On the other – I’m thinking of Michel Foucault’s notion that the power of the state is diffused through “micro-sites” like schools, workplaces and families (which have always existed), but that’s more of an incidental thought.