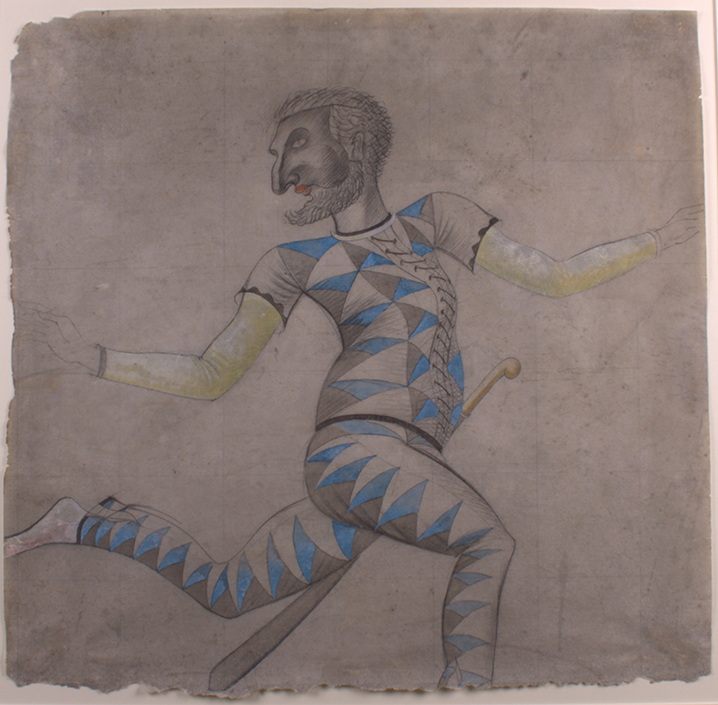

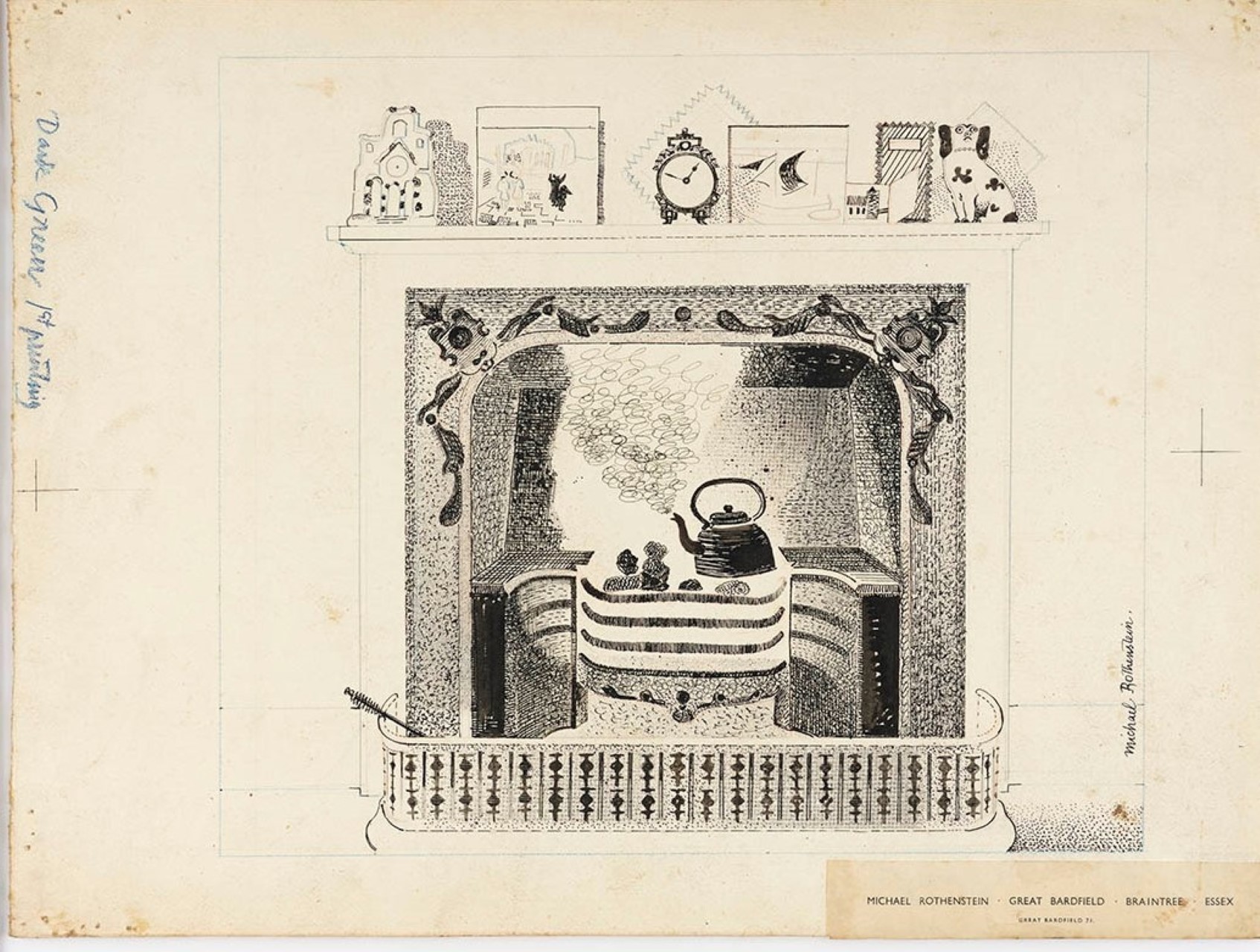

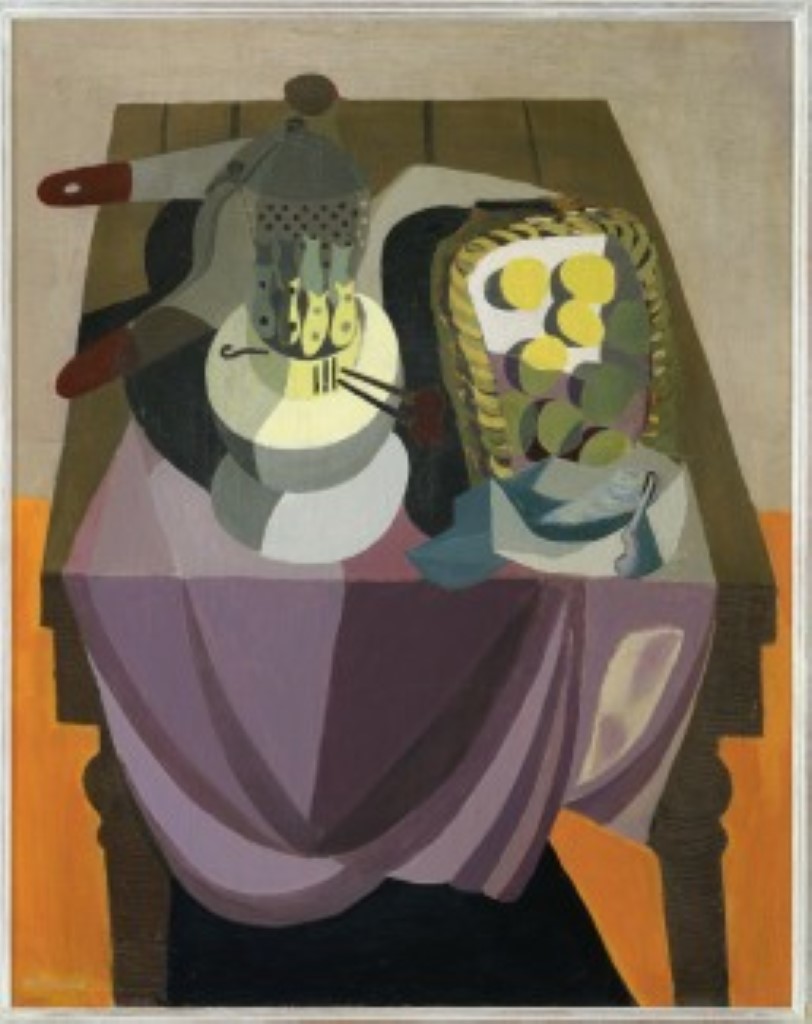

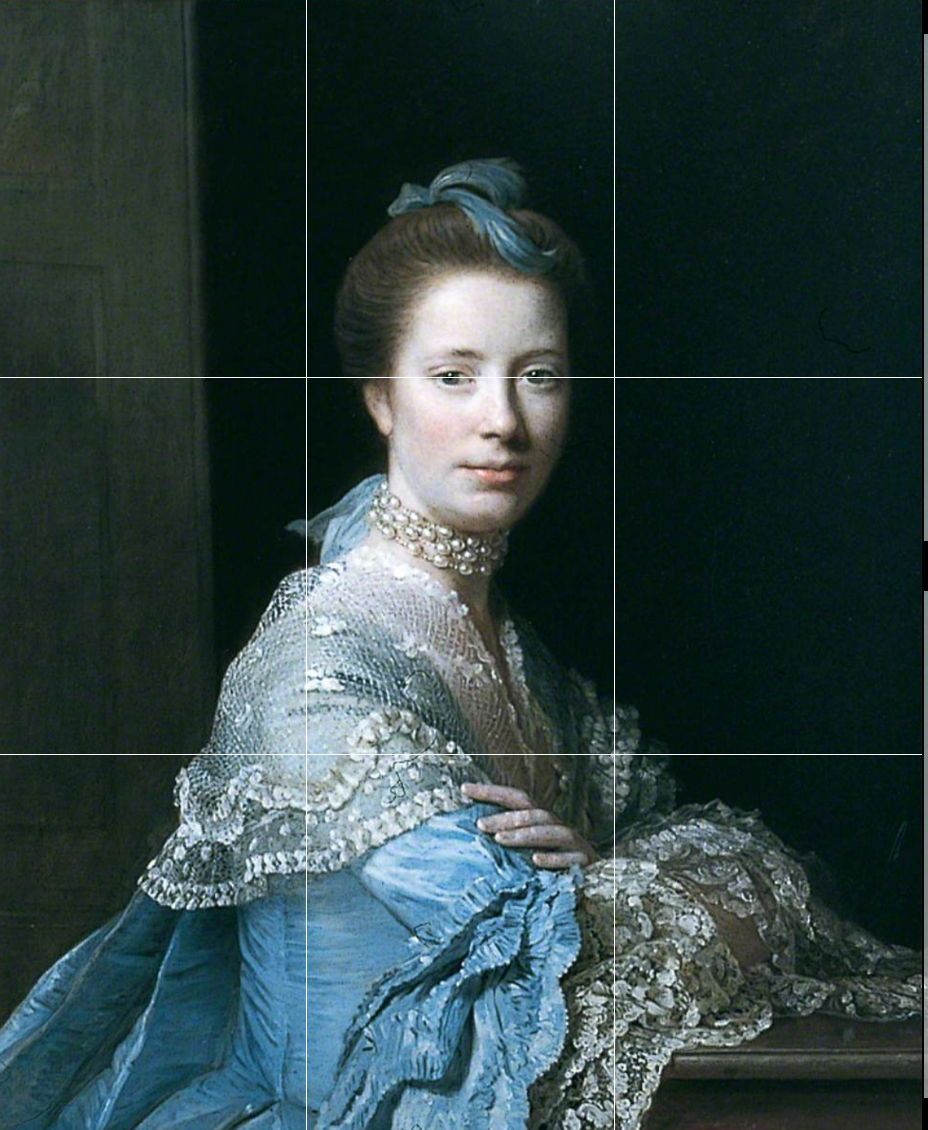

Winter drags on, cold and damp. I headed to York to visit the art gallery for a second time, this time lingering in front of the non-working automaton clock (possibly by the designer of the silver swan in the Bowes Museum). It needs to be wound up regularly to work properly, but it fell victim to Covid lockdowns. I thought how you really would want to have your portrait painted by Allan Ramsey if you were an eighteenth-century bigwig – and then noticed, as I cropped the image, how neatly it was arranged on a grid. What to do with your bits and pieces of medieval religious art: arrange them as a polyptych. There were three abstract paintings hung together and I entertained myself by wondering why I admired one and not the other.

The best bit was stumbling across an exhibition of works by someone I had never heard of before: Harold Gosney, now a very old man, who seems to have been creating all his life. There was a sense of integrity and coherence in his work. His sculptures of horses from patches of metal and perspex somehow married physical grace and power with the inorganic materials.

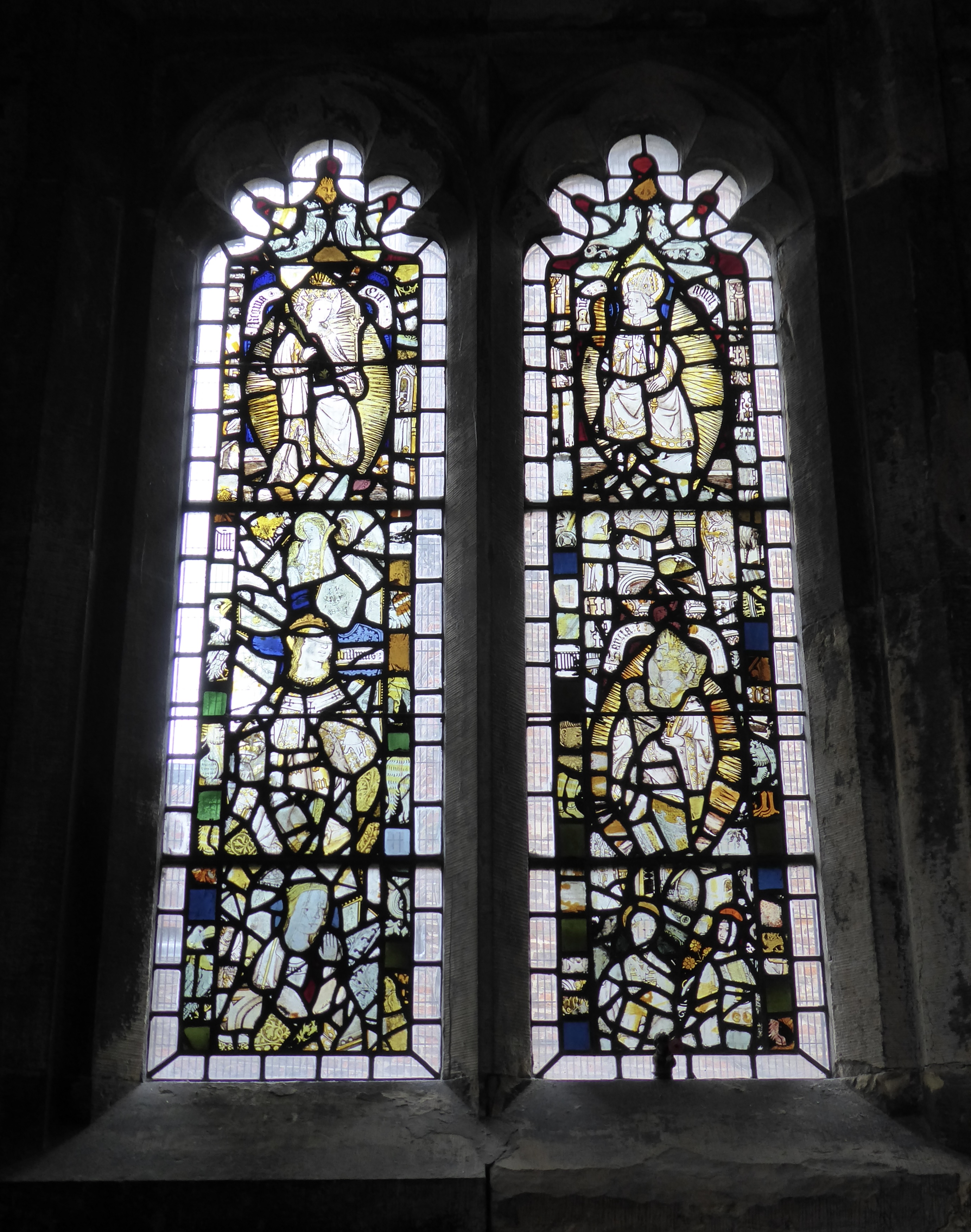

I had time to look for the redundant Holy Trinity Church in Goodramgate. Many centuries of building in one small church, box pews (how did they affect the congregation’s experience of services?), some 15th-century stained glass, and a squint between the small chapel and the main altar.