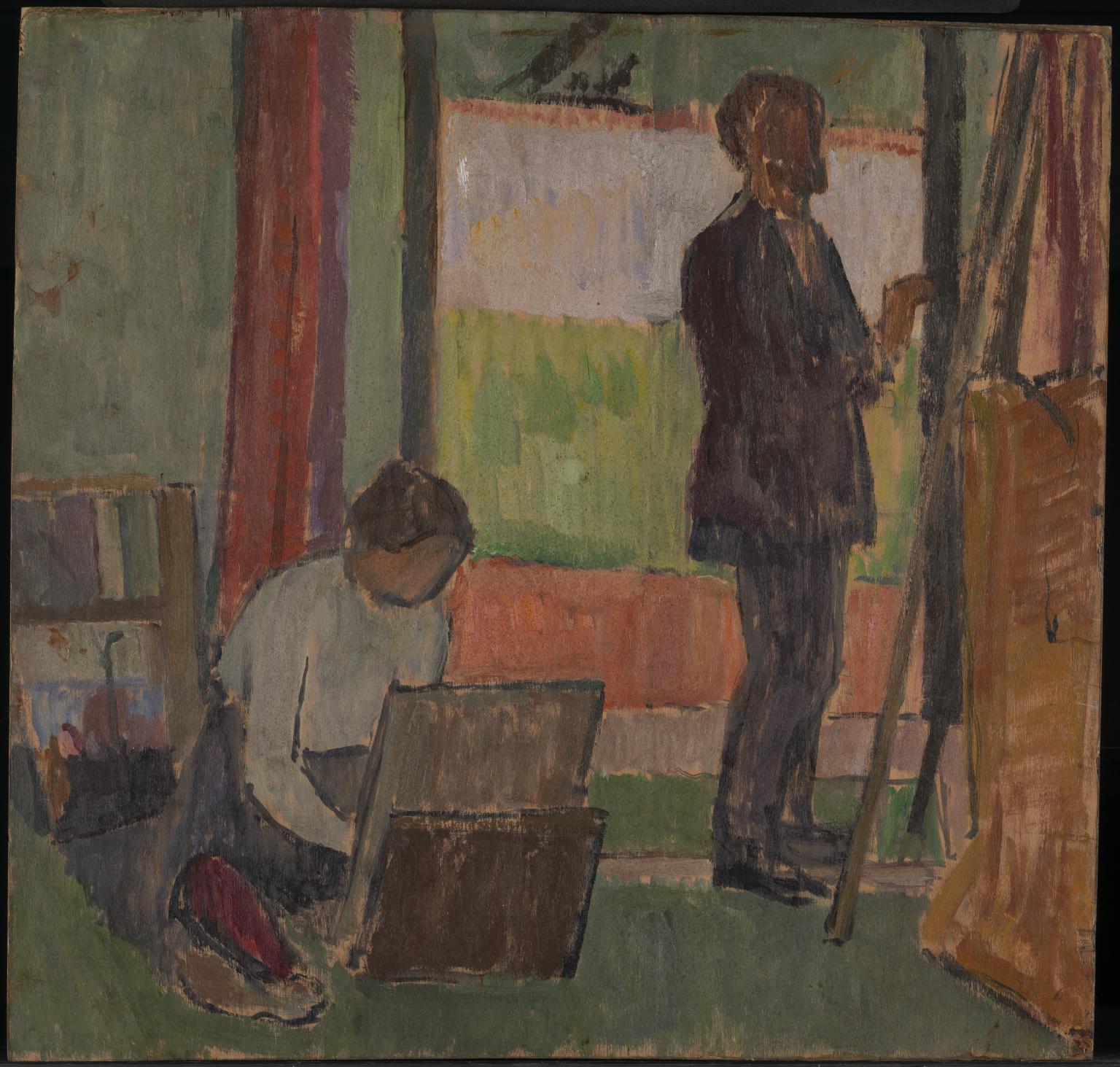

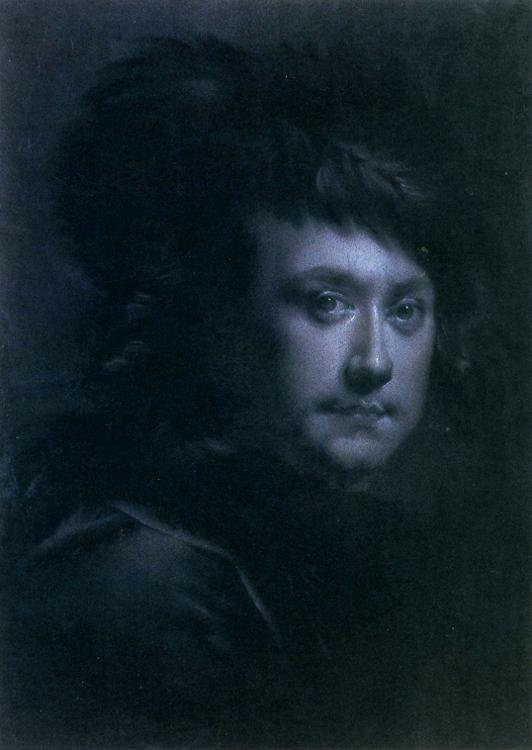

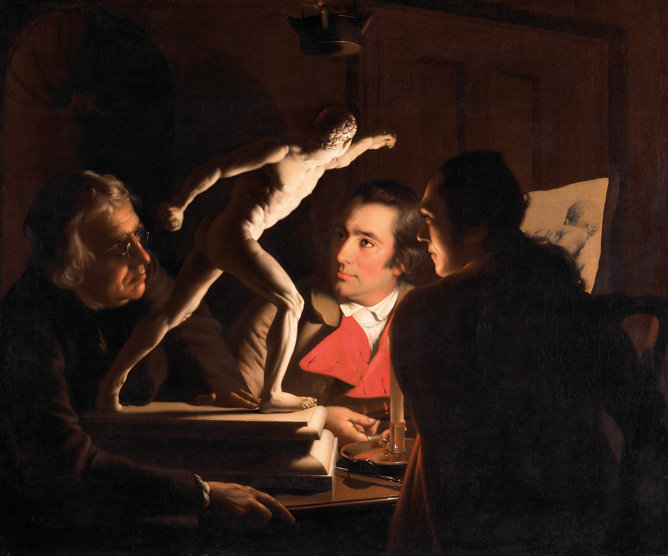

After two exhibitions in one afternoon, I thought that what Joseph Wright of Derby (the “of Derby” to distinguish him at that time from another painter of the same name) and Cecil Beaton had in common was creating their own distinctive worlds. One serious and one frivolous. The Wright exhibition was small, containing only a few large canvasses (but what canvasses!), some mezzotints (Wright had an eye for wider consumption), a couple of related exhibits (e.g. an air pump and an orrery) and a rather wonderful self-portrait in pastel. I had thought of him as painter of the new “scientific” age – casting new discoveries in a mould usually reserved for the heroic or biblical – but his range was broader than that. There were little tics: hidden light sources, glowing red tones. He certainly casts J Atkinson Grimshaw into the shade.

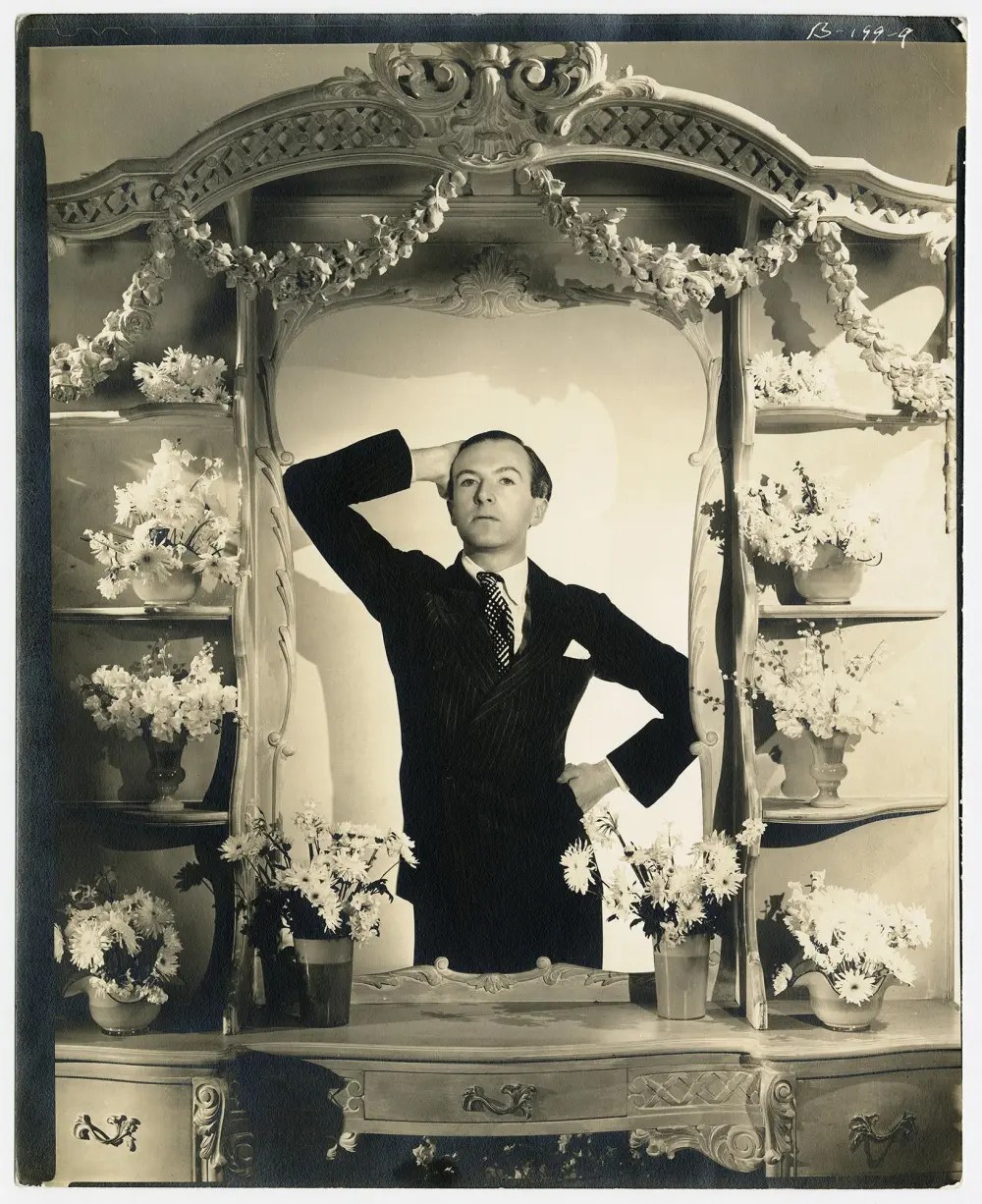

And then Cecil Beaton. The Wright exhibition was compact, and the Beaton one would have benefited from the same treatment. At times it felt like one perfect epicene profile and slicked-down hairstyle after another: the appeal of glamour (which is great) had dwindled to a yawn by the final rooms. His photographs, though – like Wright’s painting – do conjure up their own world, a mix of Brideshead Revisited and Hollywood floating in an atmosphere of superficiality and what would now come across as snobbery. There was the hiatus of WWII in all this gaiety; it killed Rex Whistler, Beaton’s friend, and sent Beaton around the UK and the world for the Ministry of Information. The Royal Family, Vogue, theatrical design . . . ah, good, the exit.

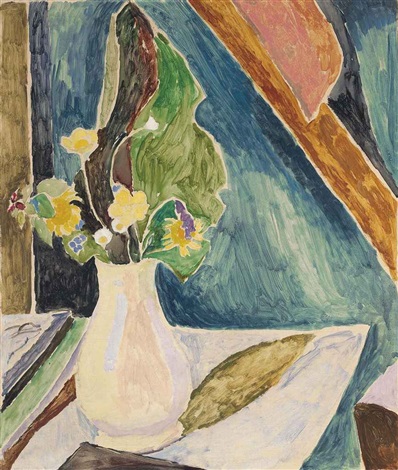

But it did send me up to room 24 afterwards to look at Augustus John’s portrait of Lady Ottoline Morrell, described by Beaton as presenting her with magenta hair and fangs. And it does!