To Tate Britain for this exhibition, which covered old and new ground for me and slotted in satisfyingly with recent thoughts. I think this makes the third exhibition solely by women artists I have seen in the past couple of years, so it’s obviously still A Thing. Some of the paintings were really not that good, but visiting the exhibition was like reading Dorothy Whipple: the insights and perspectives it afforded me had my head spinning and far outweighed any lapses.

Lots of women artists have just disappeared into the past or their work has not been attributed to them. There was a painting from the 17th century by Artemisia Gentileschi of Susanna and the Elders that has been misattributed to male painters a number of times during its existence. Nothing by Susanna Horenbout (16th century) is known to have survived, even though she was admired by Dürer.

Many of these women painters were not originally from Britain: Angelica Kauffman, Gentileschi, Horenbout, Levina Teerlinc, Maria Verelst, Mary Moser. And most of these were from families of painters/craftsmen – so perhaps these highly marketable skills pulled people across Europe in search of patrons and commissions and were worth passing on even to daughters.

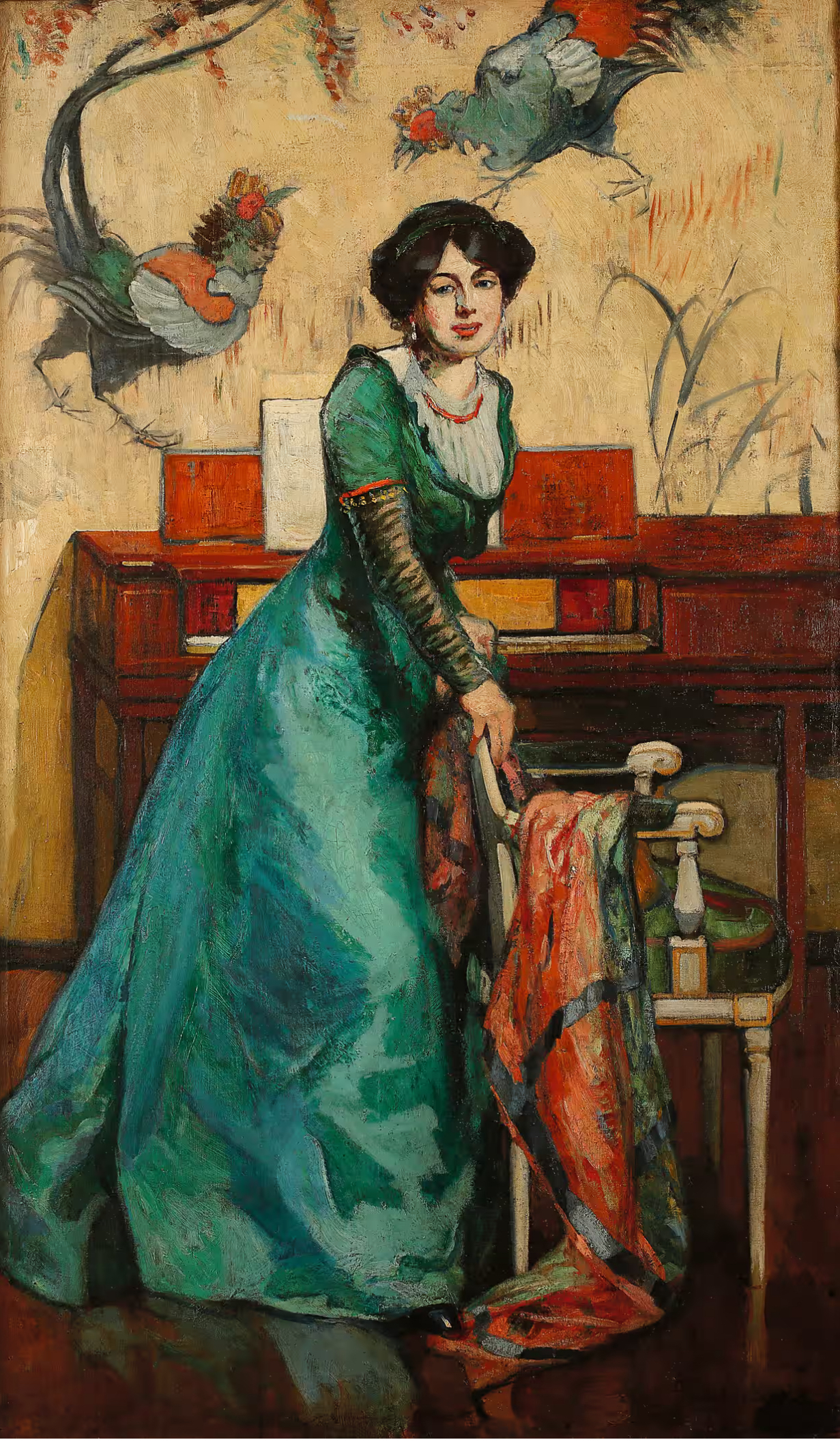

Suitable subjects for women painters were, of course, portraits (particularly of other women or children) and flowers. History painting was beyond their imagination so they’d best stick to recording real life. Painters like Kauffman kicked against these restrictions, and she produced biblical and literary scenes, sometimes with the woman as the more active figure. A score settled – even though the finished product could be a bit blah.

Actually, my favourites among the earlier works were indeed the flowers! I really couldn’t tell that Mary Delaney’s raspberry was a collage. As for the gooseberry . . .

Joshua Reynolds had a sister, Frances – which immediately set me to thinking of “A Room of One’s Own”. Frances kept house for Joshua and learned to paint by copying his works – a more respectable outcome than for Shakespeare’s hypothetical sister.

The Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (the Society of Arts) was founded in 1754 and offered cash prizes and medals in many categories, including the ‘polite arts’ – e.g. patterns for embroidery, copies of prints, drawings of statues and of ‘beasts, birds, fruit or flowers’, as well as landscapes. Some prizes were specifically intended for young women and could lead to a career.

And a career was possible: Mary Beale and others had already proved that. Some of it does look a bit churned out – Joan Carlile’s re-used silver dress, for example.

The Royal Academy was founded in 1768 (with Kauffman and Moser amongst the founders) for the really serious stuff and showed work by women artists. Materials mattered. Oil paint took a long time to dry (I remember Mary Beale’s husband experimenting with ways of getting it to dry faster to speed up the production line) , but more malleable media were frowned on. Reynolds was very dismissive of pastels, and traditionally domestic crafts such as needlework were beyond the pale.

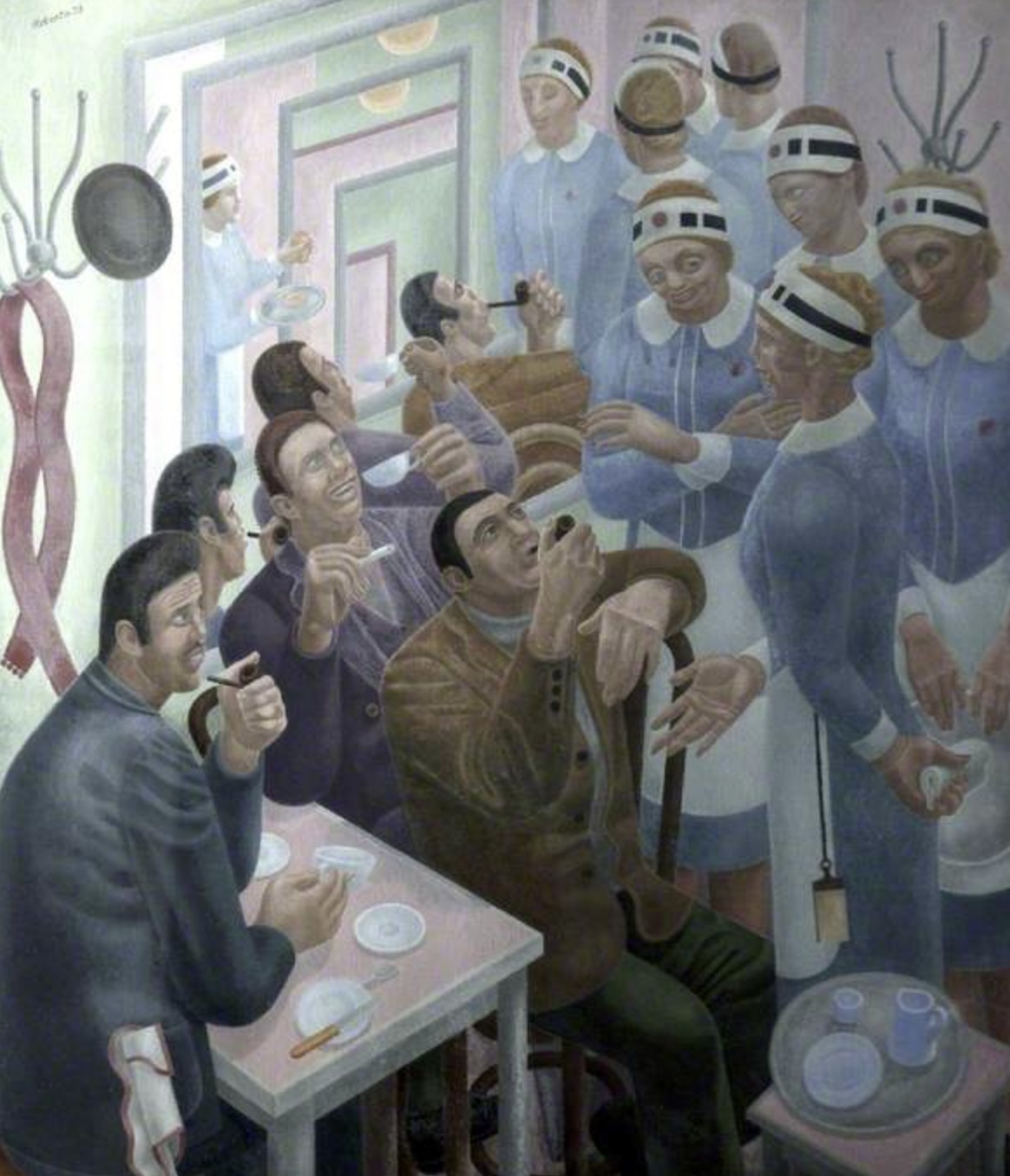

Florence Claxton’s “Women’s Work” was a brilliant dissection of the female role: essentially man’s servant, but some at the margins were plotting their escape. It put me in mind of Ford Madox Brown’s “Work” in its shape and packed social commentary.

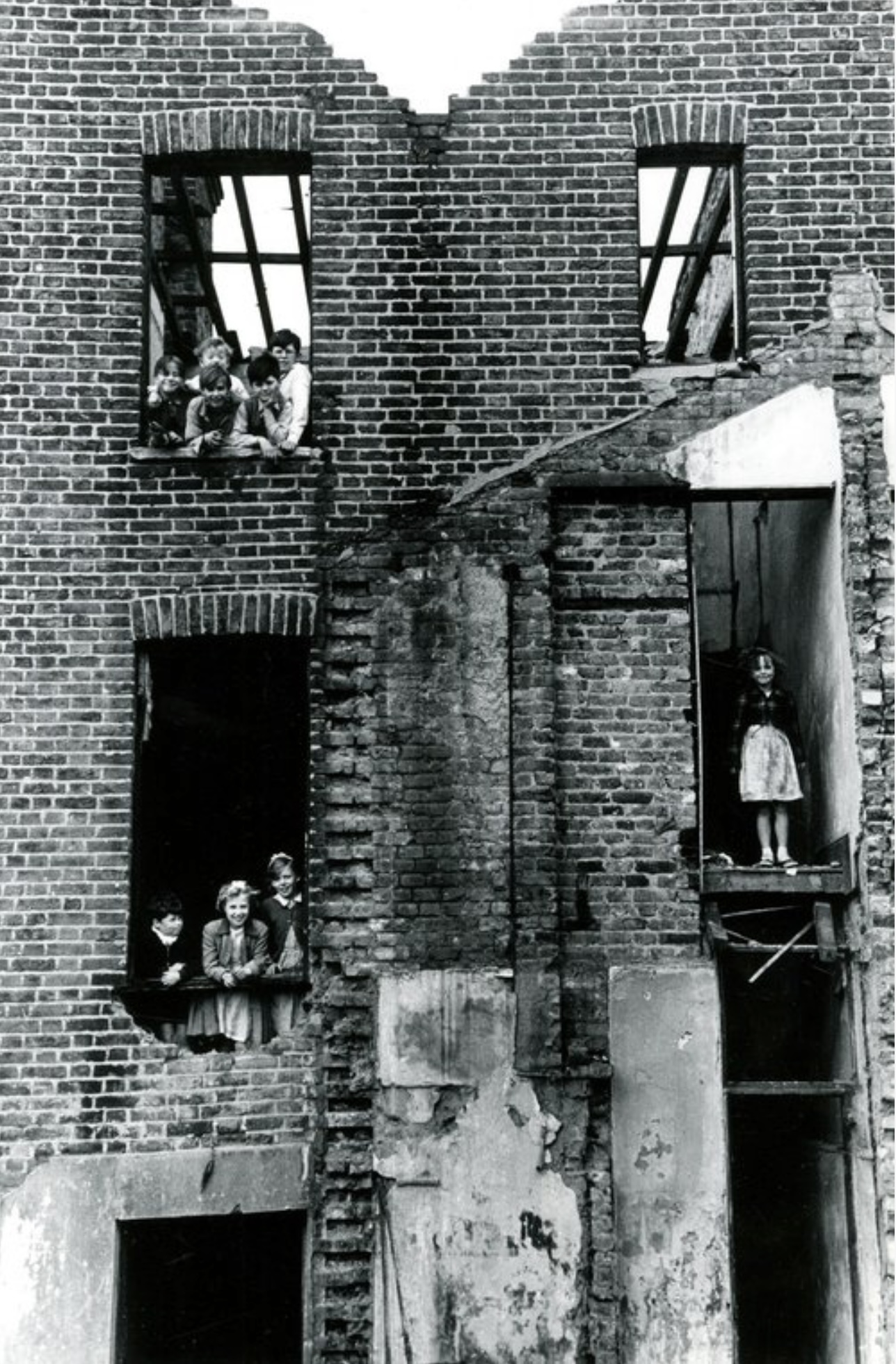

Once women were able to study art (but not life drawing until 1893), things changed. They could paint out of doors (if not à la Caspar David Friedrich, then at least in gardens and orchards), join artistic communities and even paint female nudes. The first woman was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in 1860, and with the founding of the Slade School in 1871 women were offered an education equal to men’s.

Another blob of red in “The Passing Train”. The way the pattern dominates everything in “The Deceitfulness of Riches”. Too many Ethels though: Wright, Walker (I saw “The Garden” at the Laing, I believe) and Sands.

There was a row of paintings by Laura Knight of women in coastal scenes, which were illuminating. In the watercolour the bathers seemed to blend into the landscape like nereids, but in the later paintings the female form is more dominant. The absence of a horizon in “At The Edge of the Cliff” turns it into a brooding scene.

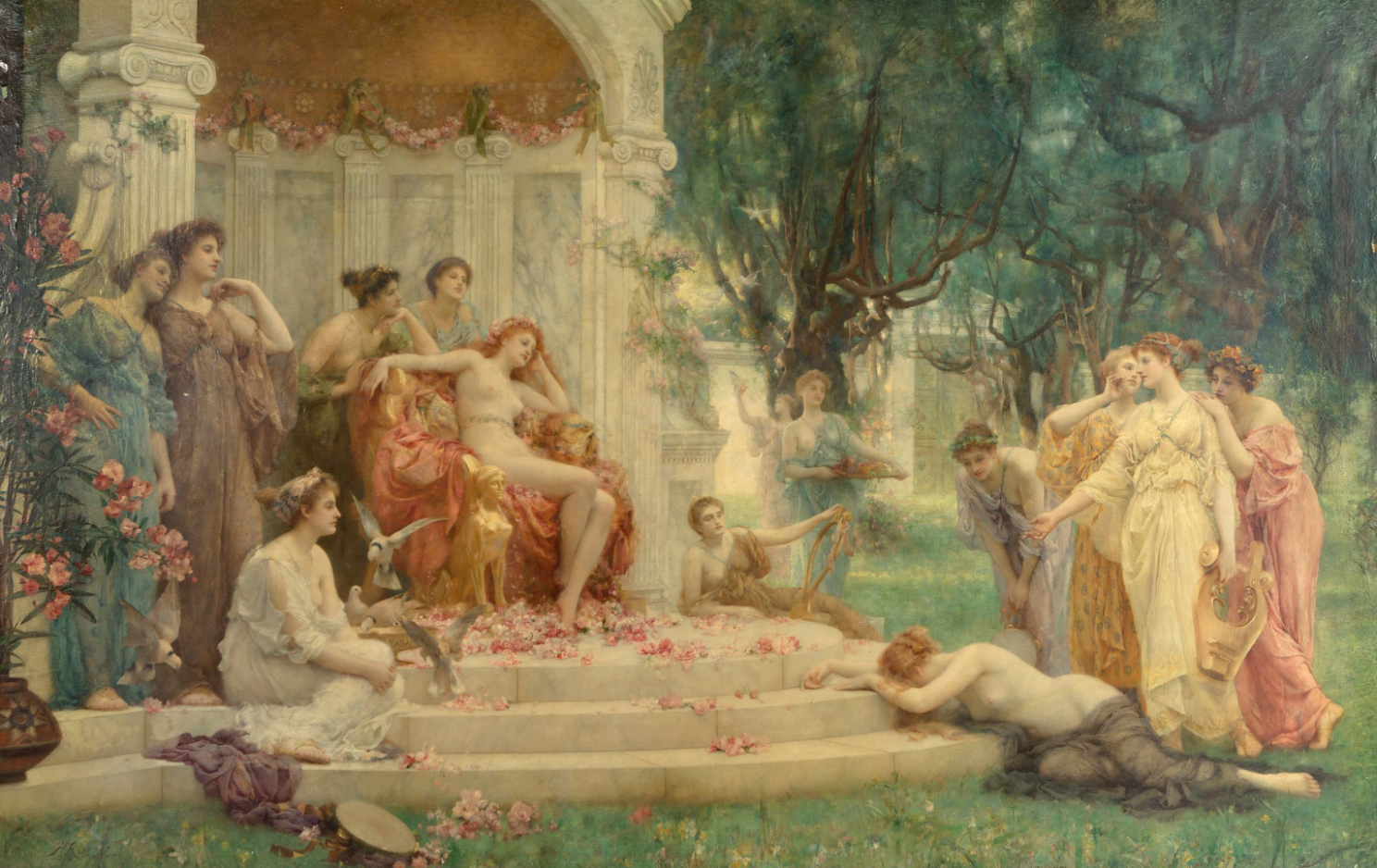

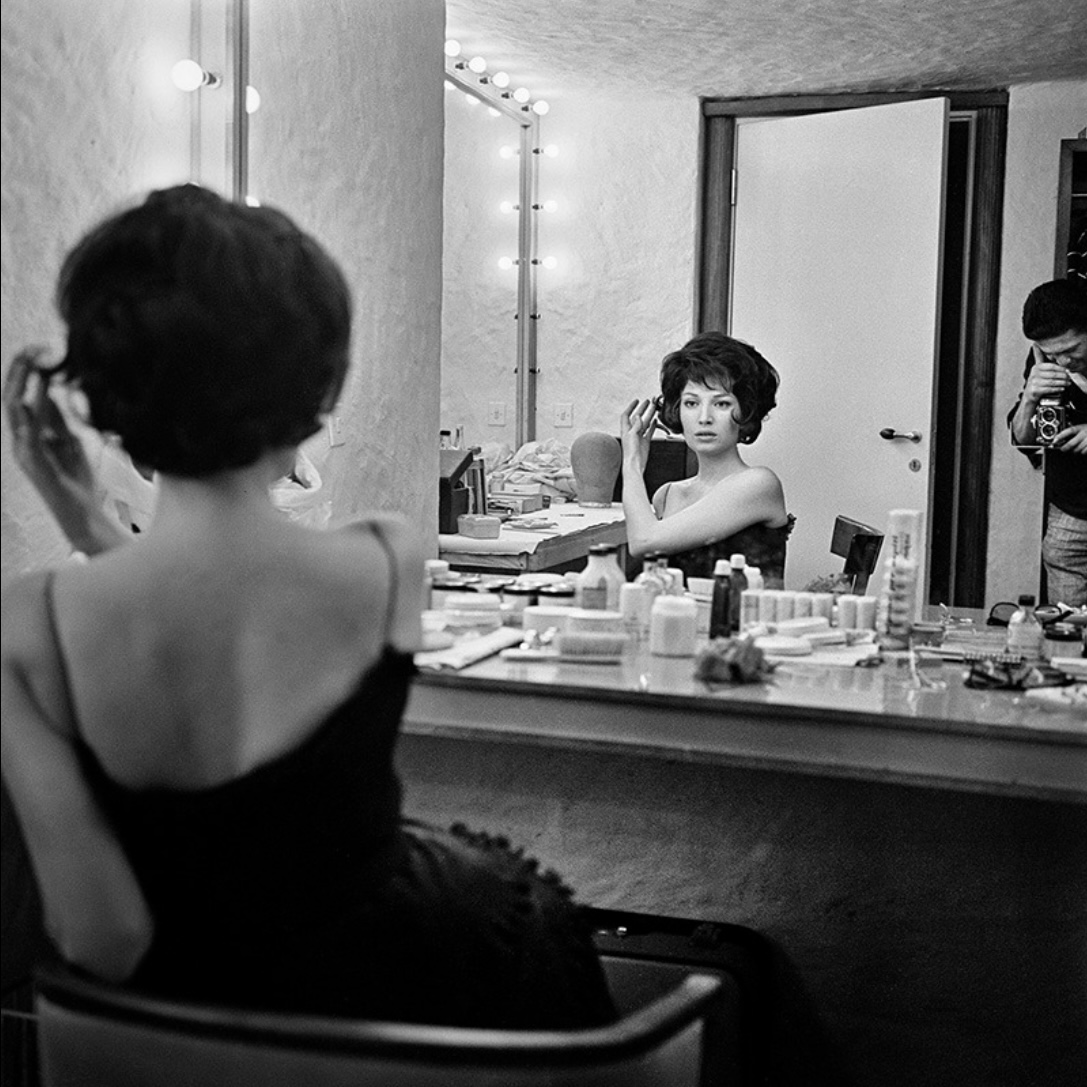

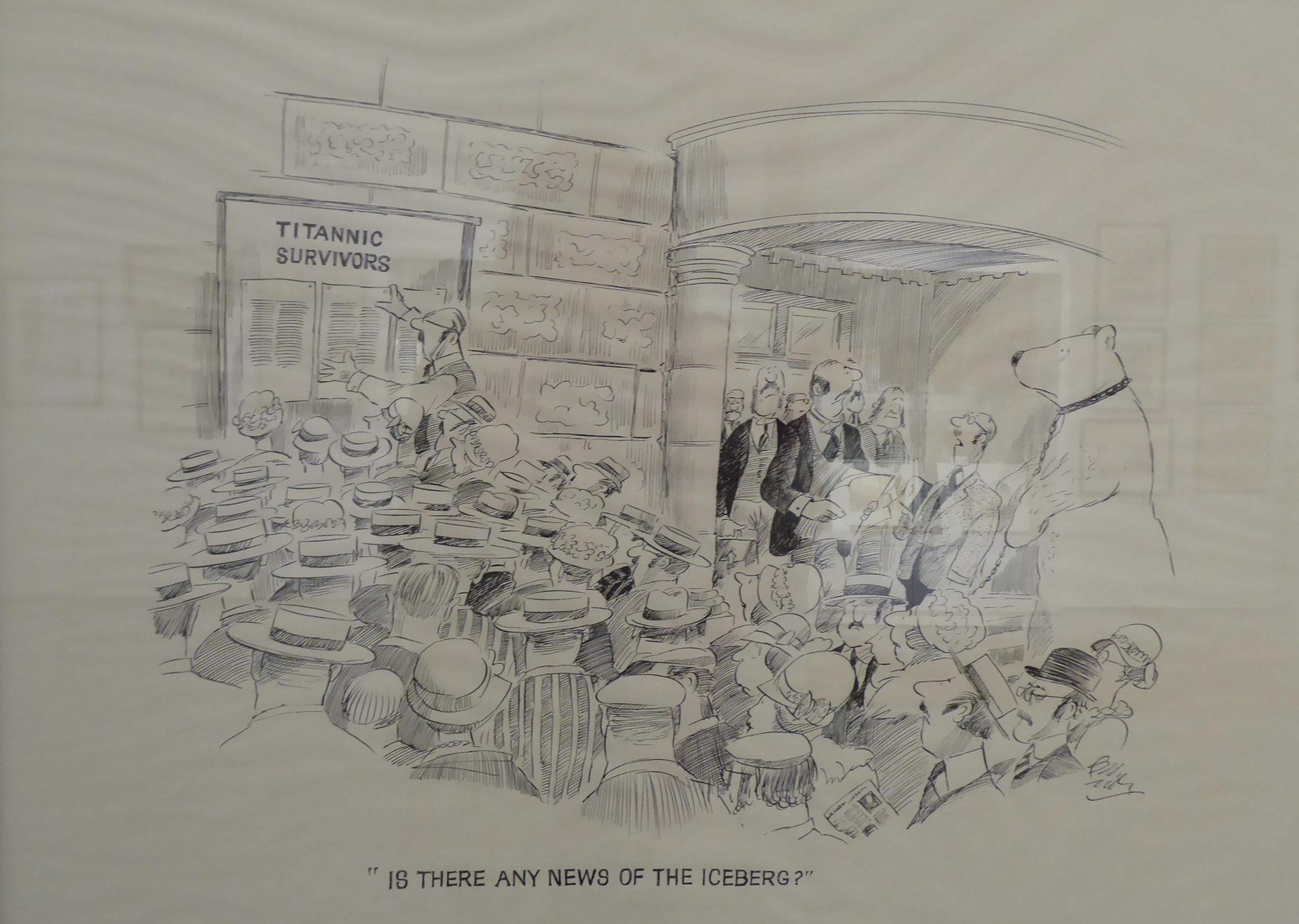

Oh, the significance of a slipped shoulder strap! (John Singer Sargent’s original “Madame X”, Monica Vitti yesterday, and today “A Modern Cinderella”. Shocking . . . apparently.) And the male gaze again. I’m not sure the theory always holds up: I really couldn’t see any difference between the “gaze” of “Psyche Before the Throne of Venus” and anything by, say, J W Waterhouse or Lord Leighton.

And then more paintings that show that a woman artist is no more pin-down-able than a male artist. After all, what do Elizabeth Butler and Gwen John have in common?

And, finally, the plane trees outside the Tate have been severely pruned as if they are topiary.