My aim in coming here was to see the cathedrals of Amiens and Rouen. I didn’t do much homework; had I done so I would have found out how long the train journey from Amiens to Rouen takes and how infrequent the trains are. As well as discovering that Rouen cathedral closes for lunch. But – n’importe. I’ve had a lovely four hours in Rouen. The sun shone, it was warm enough to take off my woollie, and I encountered Gothics both Flamboyant and Rayonnant.

But first Amiens. I walked past the town hall on the way to the station: very French and imposing in a double-winged neo-classical style topped off with a baroque clock. Views of the cathedral down side streets. Then a bit of art deco with the Grands Garages de Picardie. At the railway station I stopped to look at the mid-century skyscraper I’d seen on arrival and then noted how it seemed to be of a piece with the station – monumental on almost Stalinesque lines. Wikipedia tells me that the station was destroyed in WWII by Allied action (the previous station having been destroyed in WWI) and rebuilt by Auguste Perret, a pioneer of reinforced concrete. It’s quite as impressive as the town hall . . . in its own way.

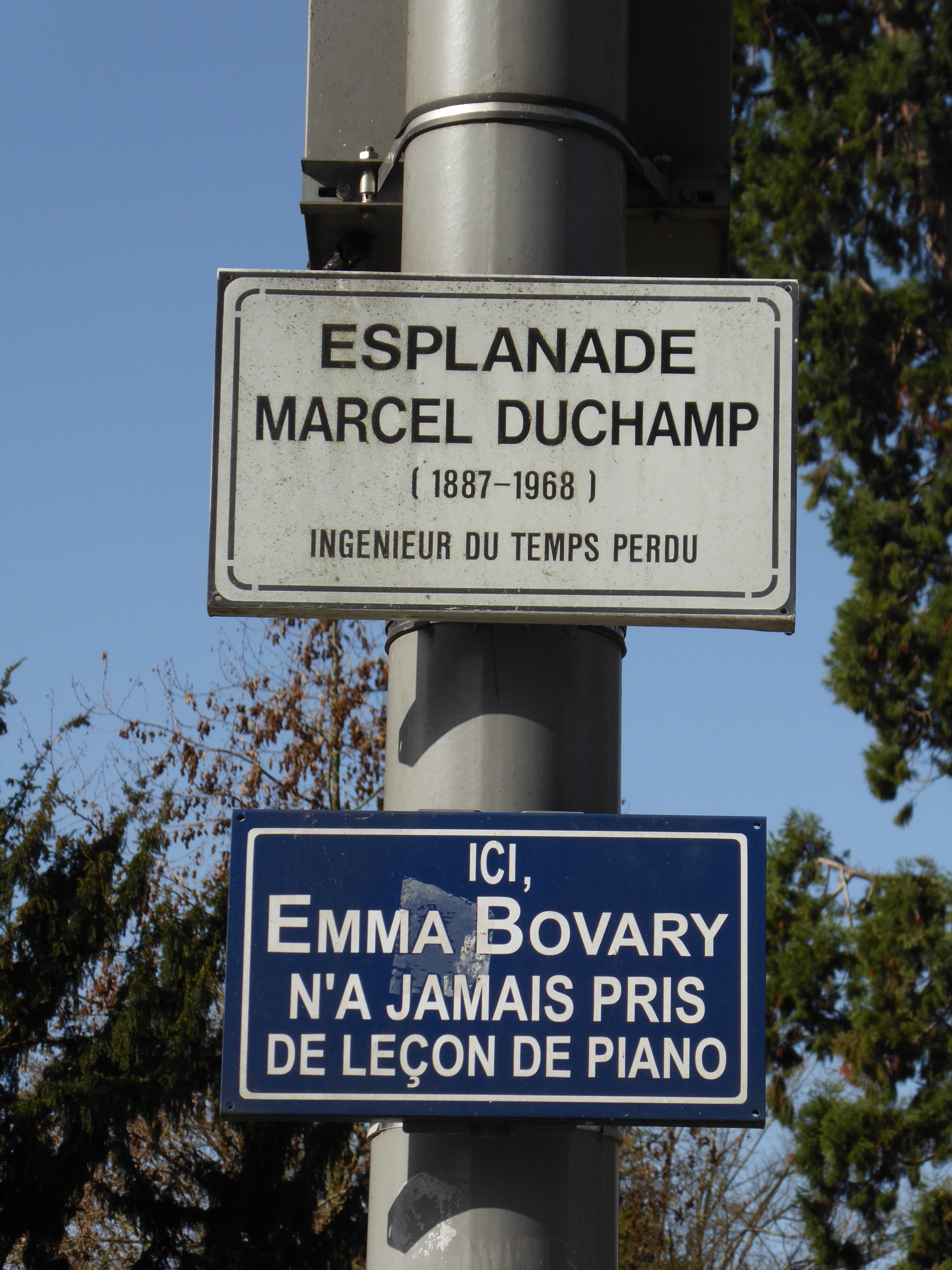

I cycled to Rouen from (I think) Dieppe decades ago and stayed in the youth hostel; all I can remember are hills. Today Rouen is definitely busier and bigger than Amiens and has many wooden buildings. Things I didn’t know/had forgotten: Jeanne d’Arc (“Que les Anglais brûlèrent à Rouen”); Marcel Duchamp was born near here; his siblings (including Jacques Villon) were also artists; Gustave Flaubert was born here and had Emma Bovary visit the city regularly. (But not for piano lessons.)

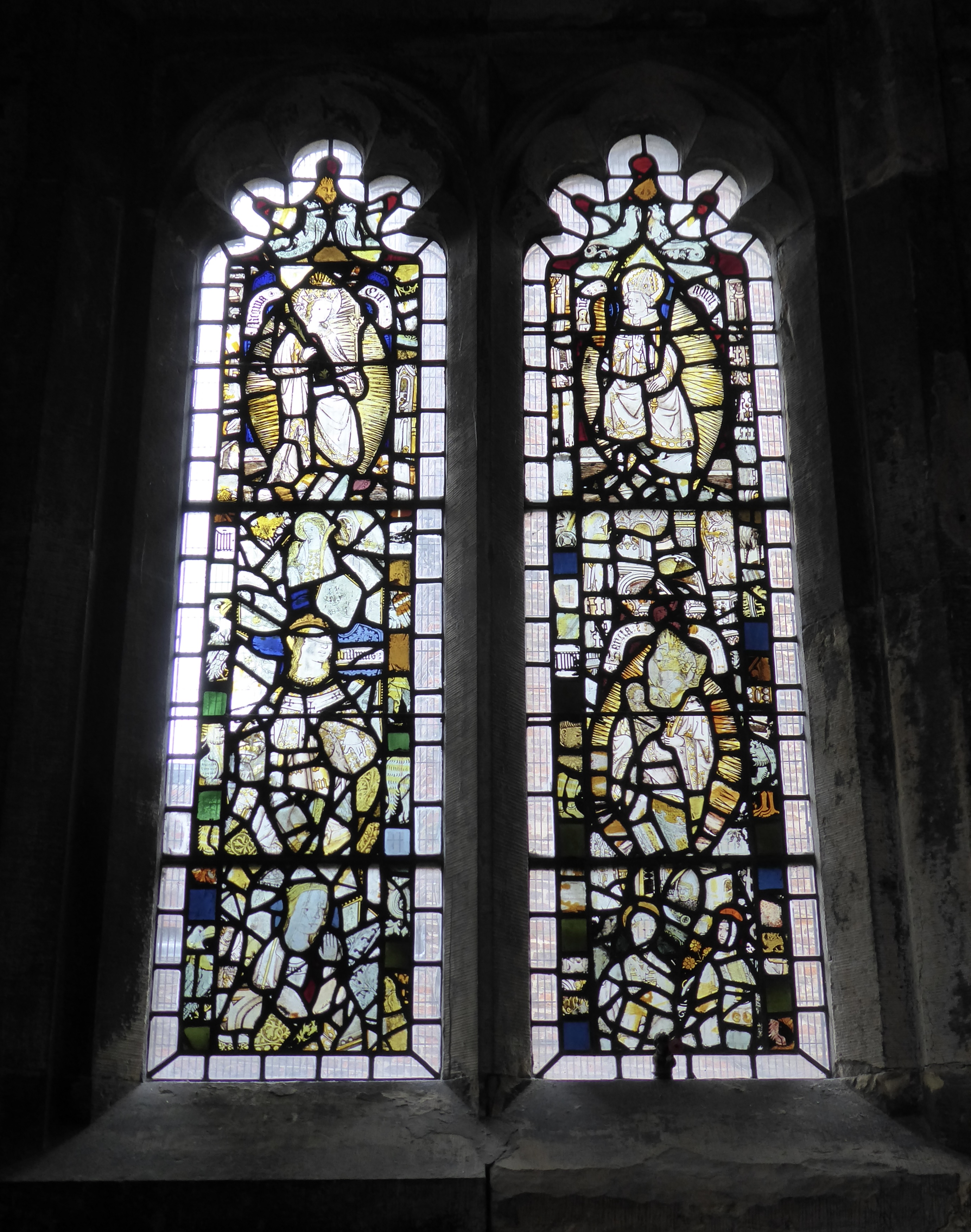

I arrived at the wonderful station. Although built in the 1920s, it’s more art nouveau than art deco. Next stop the tourist office on the Esplanade Marcel Duchamp. Then to the cathedral. Amiens cathedral has already won my heart and Rouen didn’t displace it. Taller but smaller (by volume) than Amiens, despite the width of the west front. The choir was damaged in WWII (the Allies again) and is obviously a reconstruction, and the spire is undergoing repair work. From some angles it looks as if the cathedral is made of lace rather than stone. I was also taken by the Église Saint-Maclou: Flamboyant Gothic (think carpet beaters laid one on top of each other) and moving forward to greet you. Like Amiens and the north door of Rouen, it has a grim image of the Day of Judgement.

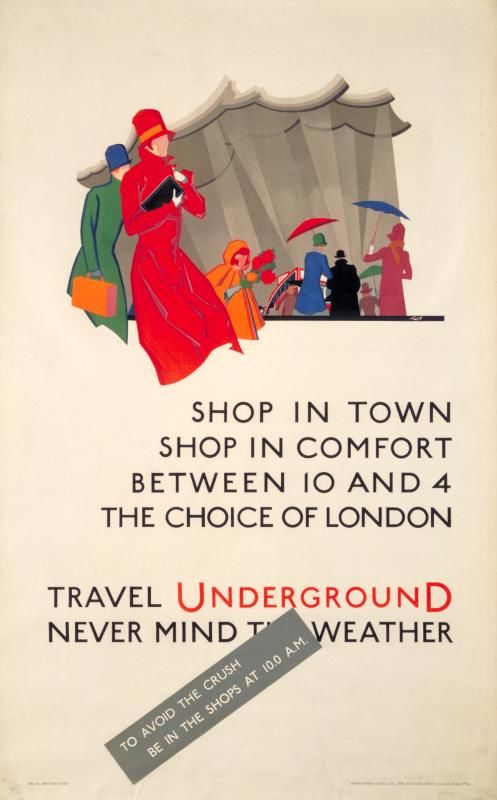

Last stop was the Musée des Beaux Arts because it seemed a shame to pass up the chance of seeing one of Monet’s paintings of the cathedral.

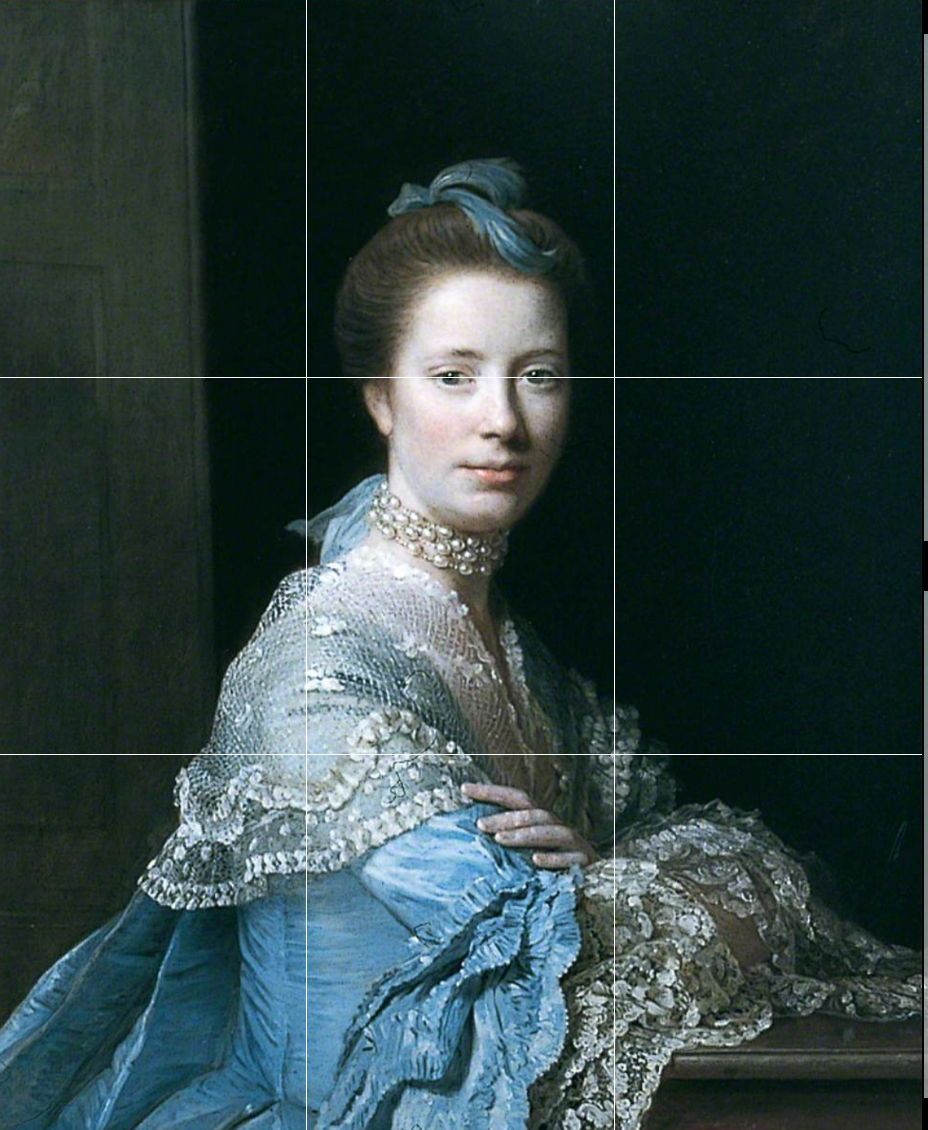

It’s a big gallery with lots of overwhelming history paintings which I skipped for the Impressionist rooms. There was also a full room of some recently restored murals by Walter Crane of some Viking fantasy. A painting by Marcel Duchamp, which was overshadowed by paintings by his brother, Gaston (who called himself Jacques Villon). Some lovely works by Alfred Sisley, a gloomy woman on a bed by Walter Sickert, and a new discovery – Jacques-Émile Blanche. Self-taught (and it showed), but I was amused by the label on his painting of “Les Six” (composers – actually only five of them in the painting and the women don’t feature in the title): it included the words “Francis Poulenc, reconnaissable par ses oreilles”.