I was rather surprised at having to give my name and date of birth in order to buy a return ticket to Arras over the counter. The foreigness of foreign countries, I suppose. Even stranger: the tickets were also emailed to me and I have no recollection of giving SNCF my email. It must have been in the far-off pre-Covid years when buying European train tickets was as common for me as buying a return to Manchester.

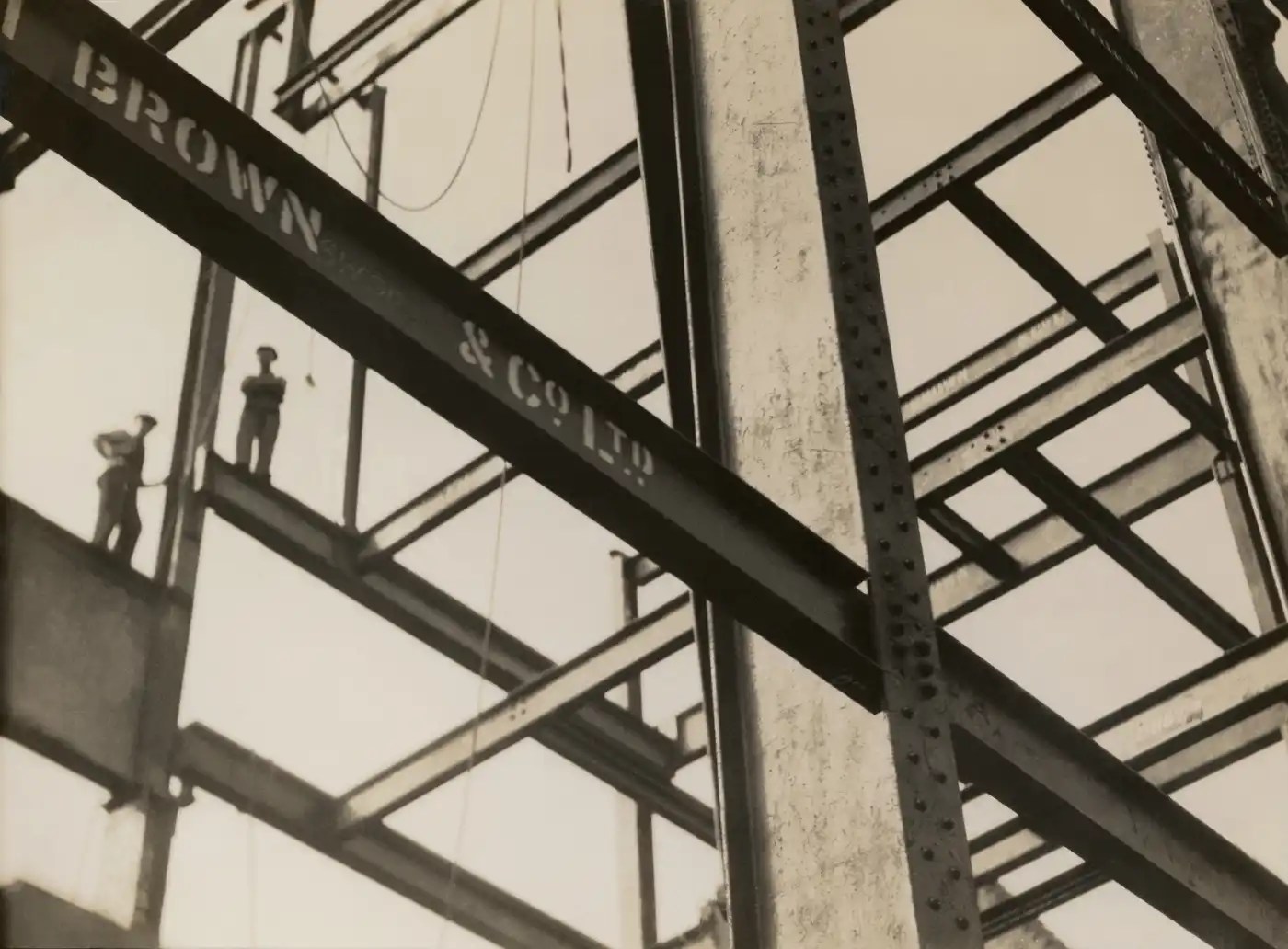

Anyway – Arras. It’s been on my mind to visit for so long that I can’t remember what prompted the inclination. It’s small but perfectly formed: improved even, since its post-WWI rebuilding means that there is a lift in the belfry to take you most of the way up to the top! Less brilliant was descending the staircase as the bells began to strike 11. It was a pleasure to wander around the Flemish-style squares in the sunshine, although my visit was shorter than expected since the Musée des Beaux Arts is closed for renovation.

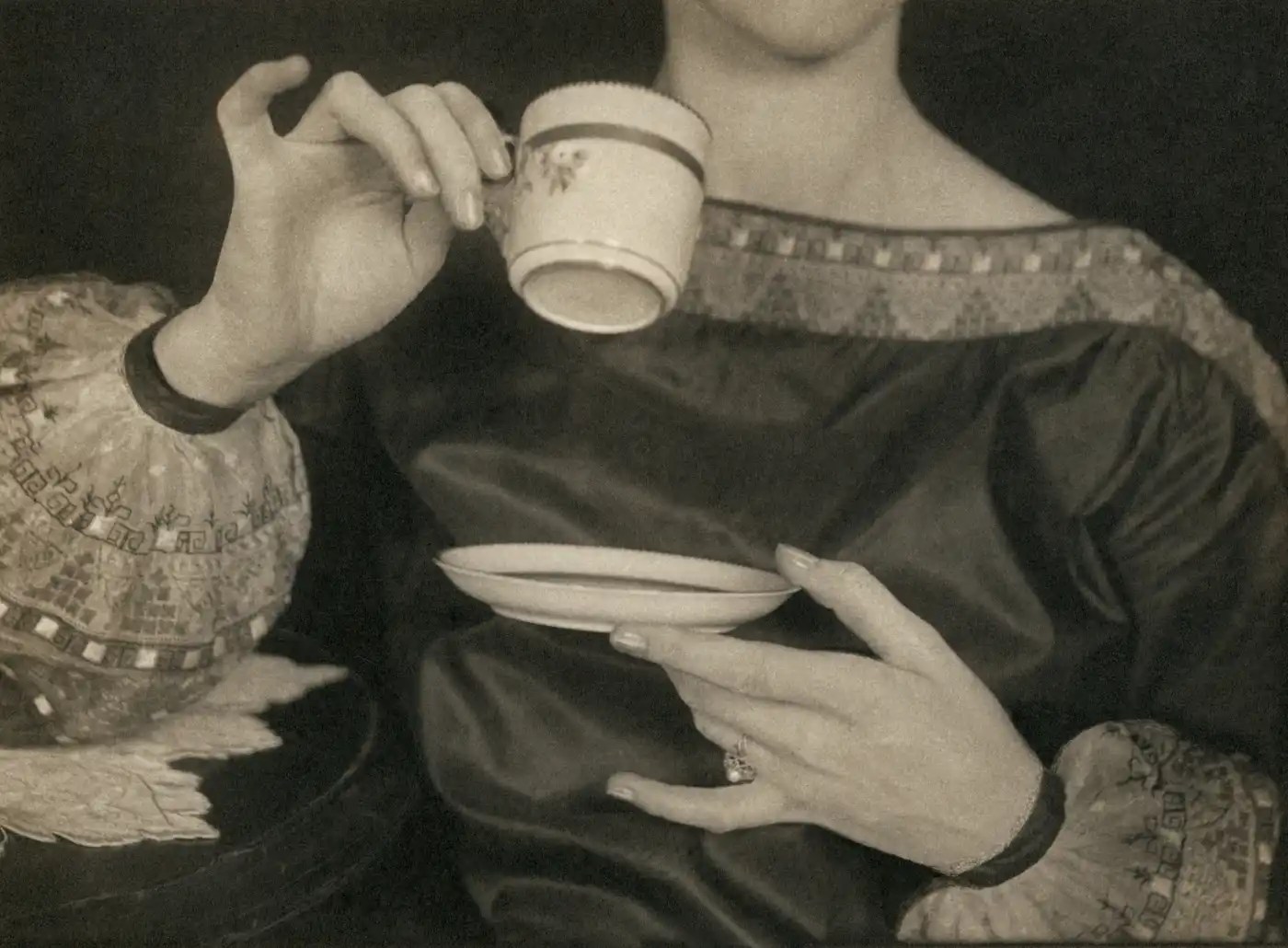

There was a little slice of French tradition in the charcuterie; a bit of a conflict between my dining preferences and my respect for other traditions there, but I’m sure the French can cope with that.

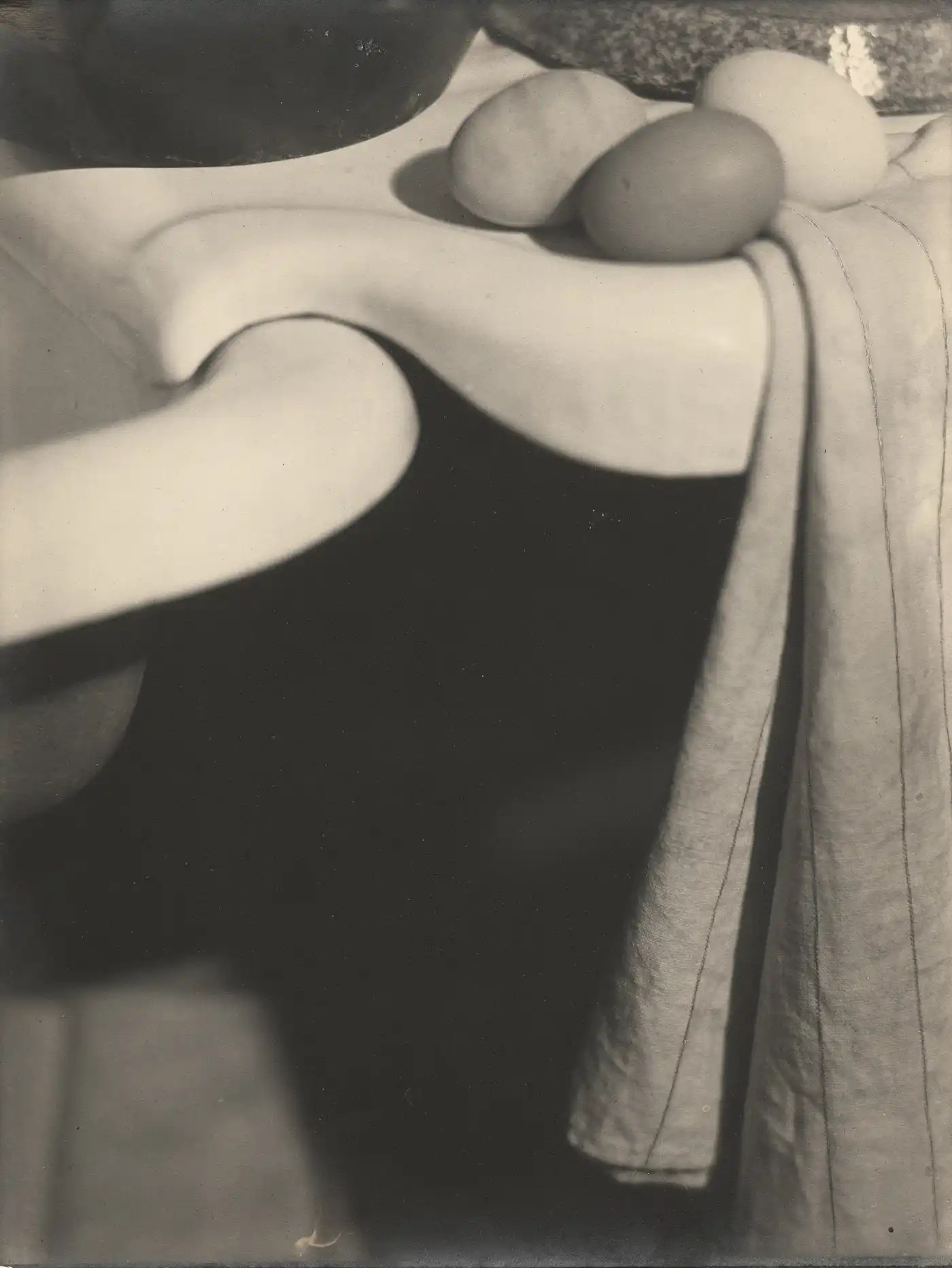

From the upper deck of the train I had ample opportunity to appreciate the dullness of the landscape: an occasional leftover spoil heap was a major feature. I shall be glad to see rolling hills again. But I suppose farming was another source of the region’s wealth back in the day, along with the coal mines and the textile factories.