I was hurrying back to the station after a late lunch and noticed the Christmas tree and lights and the way the office block resembled an open advent calendar so I had to stop. It’s bizarre really: midwinter on Midsummer Boulevard.

I was hurrying back to the station after a late lunch and noticed the Christmas tree and lights and the way the office block resembled an open advent calendar so I had to stop. It’s bizarre really: midwinter on Midsummer Boulevard.

Director Stephen Poliakoff with Charles Dance and Cassie Stuart

A dud of a film – stilted, with over-expositionary dialogue and some wooden acting; basically just not good enough to keep you in its orbit. Typical Poliakoff – a fascination with the recent past that pulls you in and a disregard for credibility or coherence that pushes you away. This one was a psychogeographic conspiracy theory with gaping holes and sidetracks that led nowhere. The scene where the secret service heavies stopped for their tea break was straight out of Astérix chez les Bretons. (Or perhaps the writer might have been hoping for more of a Blow Up vibe.)

And yet . . . While it didn’t succeed as a good film in its own right, there was something about it that set me thinking. I liked the use of locations – particularly the Kingsway tram depot that I remember (the site of which I shall walk past tomorrow) – and the sense of other lives at other times in this selfsame spot. It reminded me of my little trip into the London underground. There was some humour – just not in the attempt at mismatched couple comedy, which misfired thanks to some poor dialogue and worse acting. There was a side interest in a 1980s take on video culture and declining attention span. (So ironic that Richard E Grant announced that he hadn’t watched a film all the way through for some years when I was thinking about the off button.)

Comparisons to other films: Radio On for its interest in screens and really looking at things. I also thought of The Edge of Darkness from the 1980s and its take on buried secrets (literally and metaphorically), government conspiracy and cover-up. That also grew increasingly unbelievable as a literal plot, but such was its quality that you were carried along with it. No such luck with Hidden City.

A flying visit to York from Leeds. I more or less remembered how to get to the Minster, and I noted that even at 9.05 a.m. there was a queue outside Betty’s. On the way back I stopped to photograph a charming shop window.

In other news, snowdrops are flowering in the front garden.

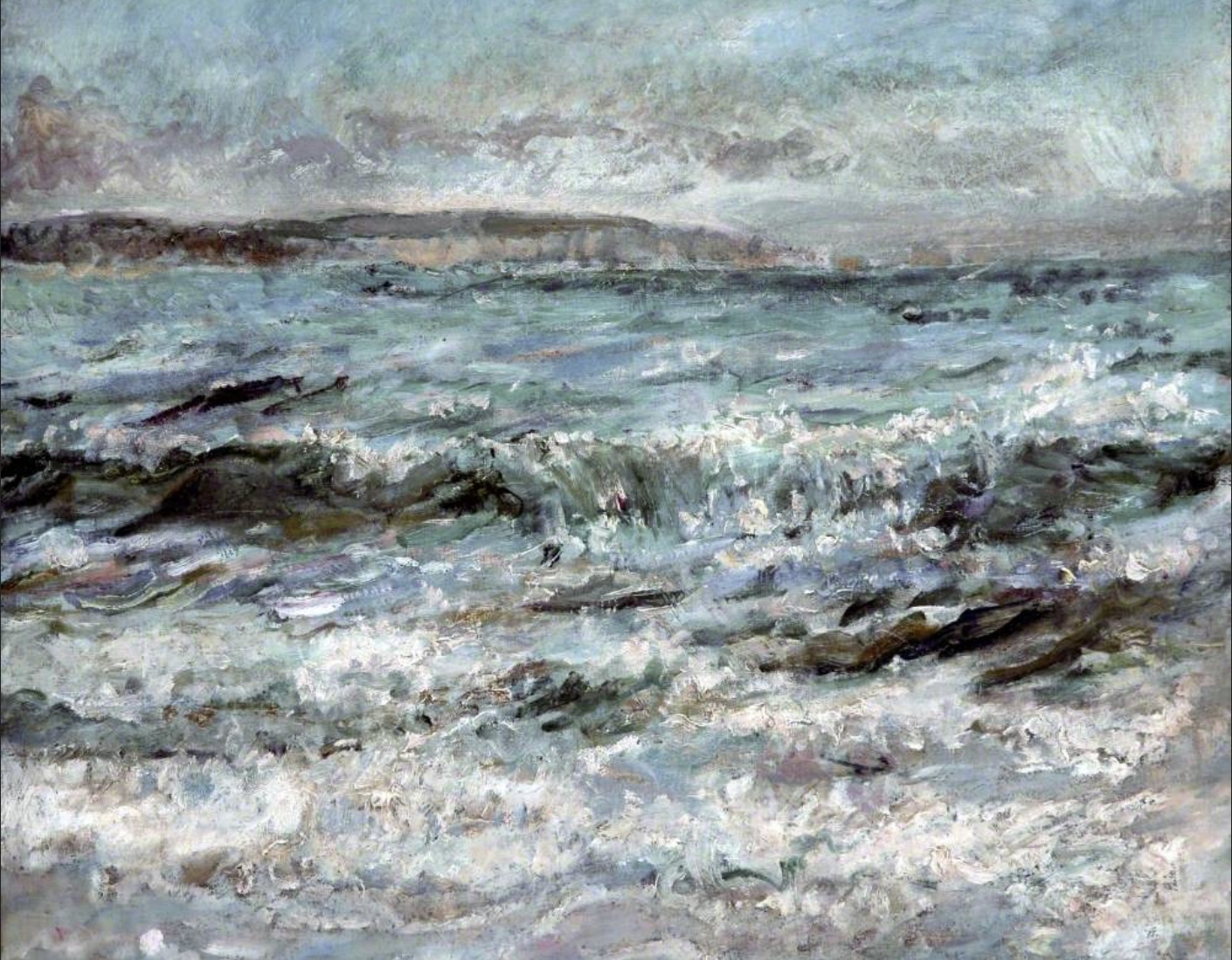

I went to see the “Turner: Always Contemporary” exhibition at the Walker, which was very good. Liverpool’s Turners have been brought together and exhibited with later 19th century and modern artists. The modern art link was a bit hit and miss; I smiled as the gallery attendant regularly asked people to stay outside the floor-taped cordon sanitaire around Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde-encased “Two Similar Swimming Forms in Endless Motion” as if she were part of some performance art. What was more interesting was comparing Turner to water scenes by Monet, Courbet and Ethel Walker. Their pictures seemed so lifeless and stilted beside Turner; somehow the mistiness of his work kept the images in motion as they came in and out of focus. I don’t think it was just a matter of fewer straight lines.

Serendipity: amongst the non-Turner paintings was one of Dordrecht, which reminded me of waterbus journeys to Rotterdam. (Turner learned from older paintings.) You could follow his move from representational landscapes (albeit ones where features were re-arranged for greater artistic impact), through his “mass” prints in the Liber Studiorum (some of which I saw in Manchester) to his later quasi-abstract paintings. J Atkinson Grimshaw also secured a spot with his paintings of Liverpool’s Custom House on the front; they are indeed wonderful, and you can see the build-up of paint in the foreground like mud on the cobbles.

Then I wandered around the rest of the Walker, venturing into galleries I barely recall visiting before. Elizabeth I by Hilliard, comparisons of Flemish and Italian Madonnas, a Rembrandt, wall after wonderful wall of 18th-century ladies and gentlemen that I didn’t have the headspace to look at individually, a Nocturne by Marchand, a view of Berne by a follower of Turner (I wonder why he didn’t make the exhibition?), and a horse painting that looked like one I had seen before.

Other things before I forget: a 1783 ceramic dish with a painting of a slaving ship, “Success to the Will”, was referenced in a modern work, “English Family China”, from 1998. They are cast from real skulls (never have the words “bone china” sounded so sinister) and implicitly comment on the link between wealth and horror. There was a painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, which, unsurprisingly, made neither the National Gallery nor this exhibition. I gazed at a lovely 15th-century Book of Hours and clocked another Beuckelaer. He must have churned them out.

The Christmas market was set up in the square outside and I contemplated a ride on the big wheel – but it was raining steadily and there was no inviting movement from the wheel, so I headed off for lunch instead.

Then the Museum of Liverpool for an exhibition on treasure unearthed in Wales and the north west of England. (A magnifying glass would have been useful.) Some of it was indeed treasure – gold or silver – but some had little value even at the time. The third-century Agden Hoard, for example – c 2,500 Roman copper alloy coins (“radiates”) from a time when galloping inflation made them almost worthless. There was also the golden Mold cape, which I have seen at the British Museum.

The sky was brighter as I left, but the big wheel was still static so I caught my train instead.

Is this the third ballet I’ve been to in my life? (Giselle and Romeo and Juliet are the others. Plus something on stage in a school.)

This was absolutely wonderful. Everything was a delight: dancing, costumes, scenery, set transformations. The storyline is flaky, particularly after the interval – but who cares when it is so entertaining? It’s a pantomime for grown-ups.

I noticed that the average audience age was a lot lower than for an opera. Not surprising really since it’s a magical crowd-pleaser for everyone. In the foyer I found myself in a copse of incredibly slender and upright girls; I later learned that Elmhurst Ballet School had come out en masse to see it.

One of those whims you’re not sure is worthwhile. But it always is. I booked the ballet on impulse and then I came across a big wheel – which I had all to myself. Vindicated already! I then went half-heartedly to the Ikon Gallery (I still go blank in front of contemporary art) but the café was closed and the advertised mini-tour wasn’t happening; a nice lunch beside the canal seemed a better idea. However, had I not tried to go to the Ikon Gallery I wouldn’t have seen Birmingham’s Second Church of Christ Scientist (where’s the First, I wonder) nearby. Now a nightclub. My kind of mental catnip.

The Birmingham Christmas market does have some link with Germany so I was pleased to find some Nürnberger Lebkuchen. (I’m sure I can get some in Sainsbury’s, but it’s not the same.) The slowly re-opening art gallery and the Staffordshire hoard (this time with a magnifying glass) next. And I was upgraded to a suite on the tenth floor. Better and better.

I heard quite a bit of spoken German in the street; combined with the number of jovial blokes in scarves, I realised I should have checked the football fixtures. Yes: Villa v a Swiss club this evening. One other thing I noted was the glumness of the three people engaged in outdoor Christmas events whom I encountered. Note to self that it’s easier to make the best of things when they are stacked in your favour.

The Christmas Fair is in town; I blanked it . . . until the moment I saw the big wheel in Albert Square. No hesitation.