To Southport on a whim. Another one of those railway stations that was designed for more passengers and bigger trains than it receives today. (Skegness is my go-to station for that.) I’m not even sure what the front of railway station looks like, for there was an entrance to Marks and Spencer immediately beyond the ticket barrier and that was how I entered the town centre.

All towns look tatty these days; it’s particularly noticeable in places that were built for the prosperous in prosperous times. Their grand Victorian and Edwardian buildings require constant maintenance, and how can grand hotels survive in an age of Airbnb? I looked at the Venetian Bridge over the artificial lake . . . and read how popular it was in the years before the war with fancy dress and lights and gondolas. Such a disconnect with what I saw on this dull, damp day.

Fortunately The Atkinson – an all-purpose gallery, museum, library, theatre and café – has recently been refurbished and is great. I wandered round the gallery, noting the Laura Knight ballerinas that I’d seen at the Milton Keynes Gallery – and surely I’ve seen that Pygmalion somewhere? It was mostly traditional art – which was fine by me when the contemporary world was represented by a Tracey Emin neon scribble. There was so little to “unpack” there. Whereas “Lilith” . . . oh, my goodness!

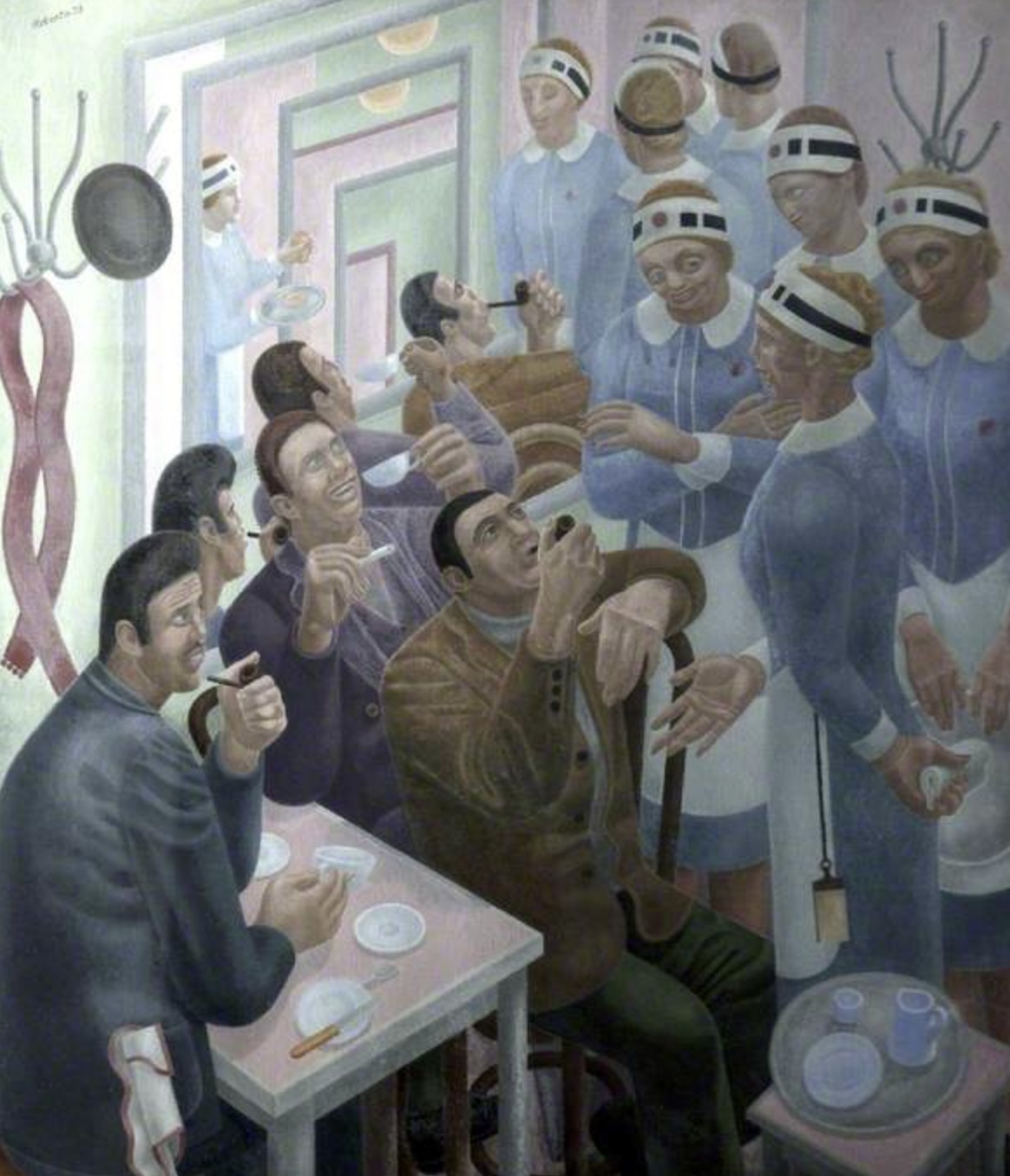

There was also an exhibition of paintings by Southport-born Philip Connard – impressionist, WWI artist, decorator, teacher. His dates are 1875-1958, which brings me nicely to the book I am reading at the moment: “The Horse’s Mouth”. (Fourth or fifth attempt, although I sailed through “Herself Surprised” thirty-odd years ago.) The fictional Gulley Jimson is of a similar era – although it would be libellous to suggest that Connard resembled Jimson in any other way. Connard’s paintings were a bit “blah”, but he could capture light on flowers beautifully – and he was certainly versatile.

There was also a small exhibition of Connard’s contemporaries, including Sickert, Cadell and Fergusson. I added to my collection of Glyn Philipot paintings too, along with one by Frank Brangwyn which made me realise how sensitised I have become to current preoccupations. I am so used to being lectured by gallery labels on the out-of-date mindsets and values behind so many works of art that it was quite a shock to come across Brangwyn’s painting of a slave market without any commentary. And I realised that I did indeed find it shocking: I thought it needed some context for a younger viewer – which was perhaps a bit patronising of me. (I also rethought my reaction to an earlier Brangwyn painting of the same name, which was an exercise in self-reflection.) I wasn’t even sure if it was a real scene or something conjured up from an overwrought Victorian imagination – like “Lilith” again. (It did rather amuse me that most of Napier’s output on ArtUK are portraits of Victorian worthies – with the occasional nude offering a possible peek into what went on beneath those top hats and bushy beards.)

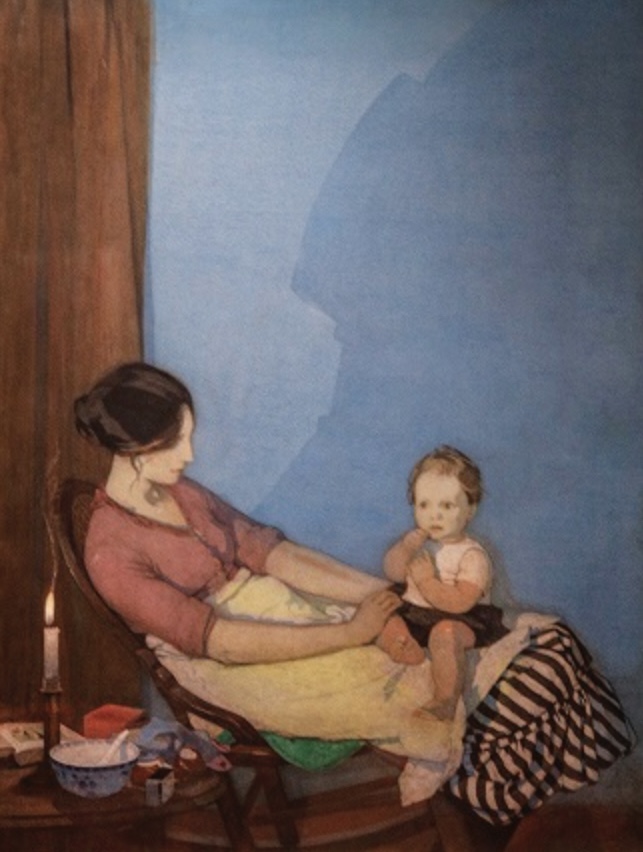

There was more information on the painting of the Village Belle, which at first glance looked like a pretty girl chatting with the village boys. Unsurprisingly it wasn’t that simple: there had been another painting showing the same girl, now clutching a child and leaving the village under a cloud. Another insight into the Victorian mindset – and/or a warning to pretty village girls everywhere.

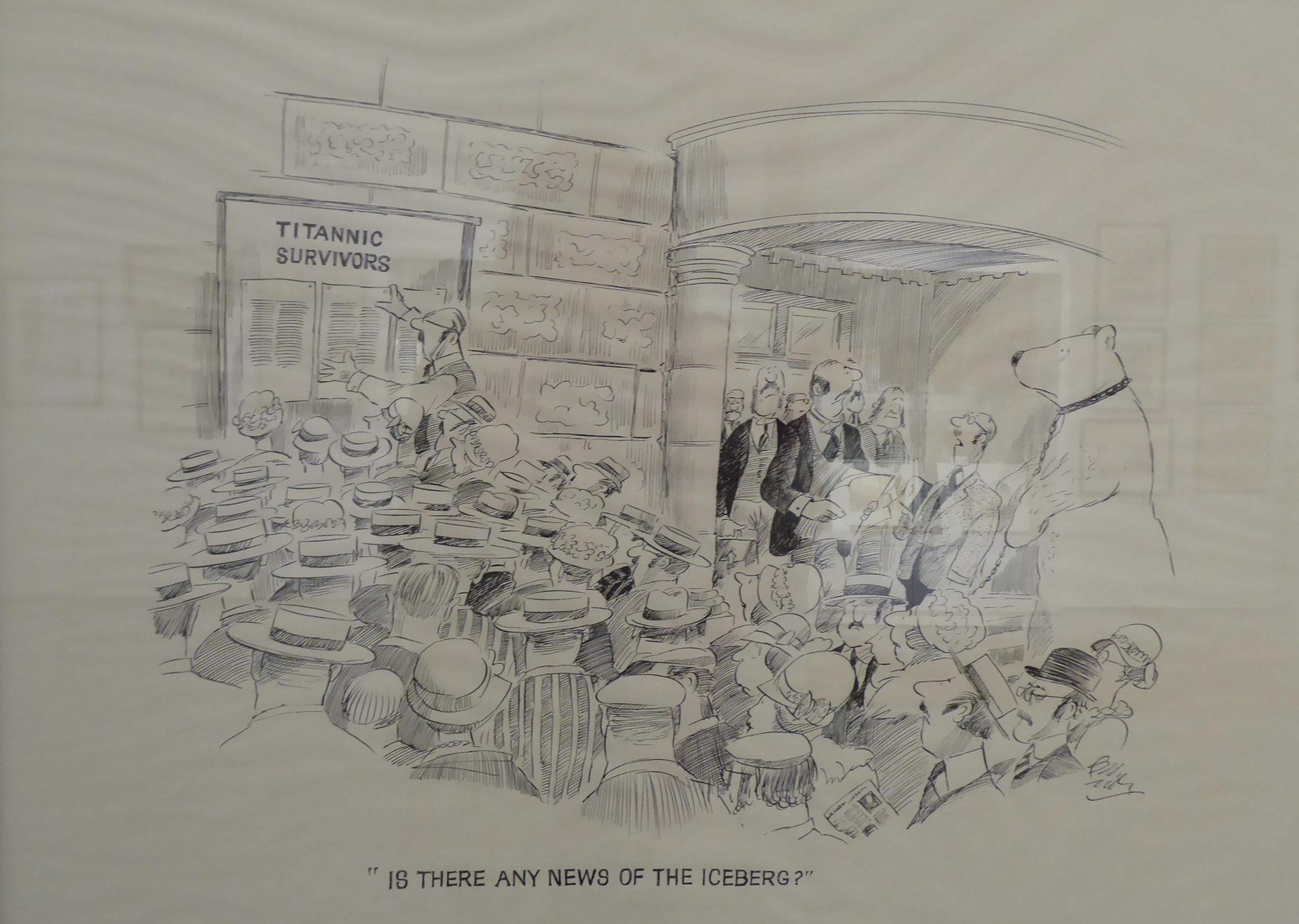

Lighter-hearted images were also available, as there was a Bill Tidy exhibition in the gallery. This was my steal, along with “The Nosegay” and Hawksley.