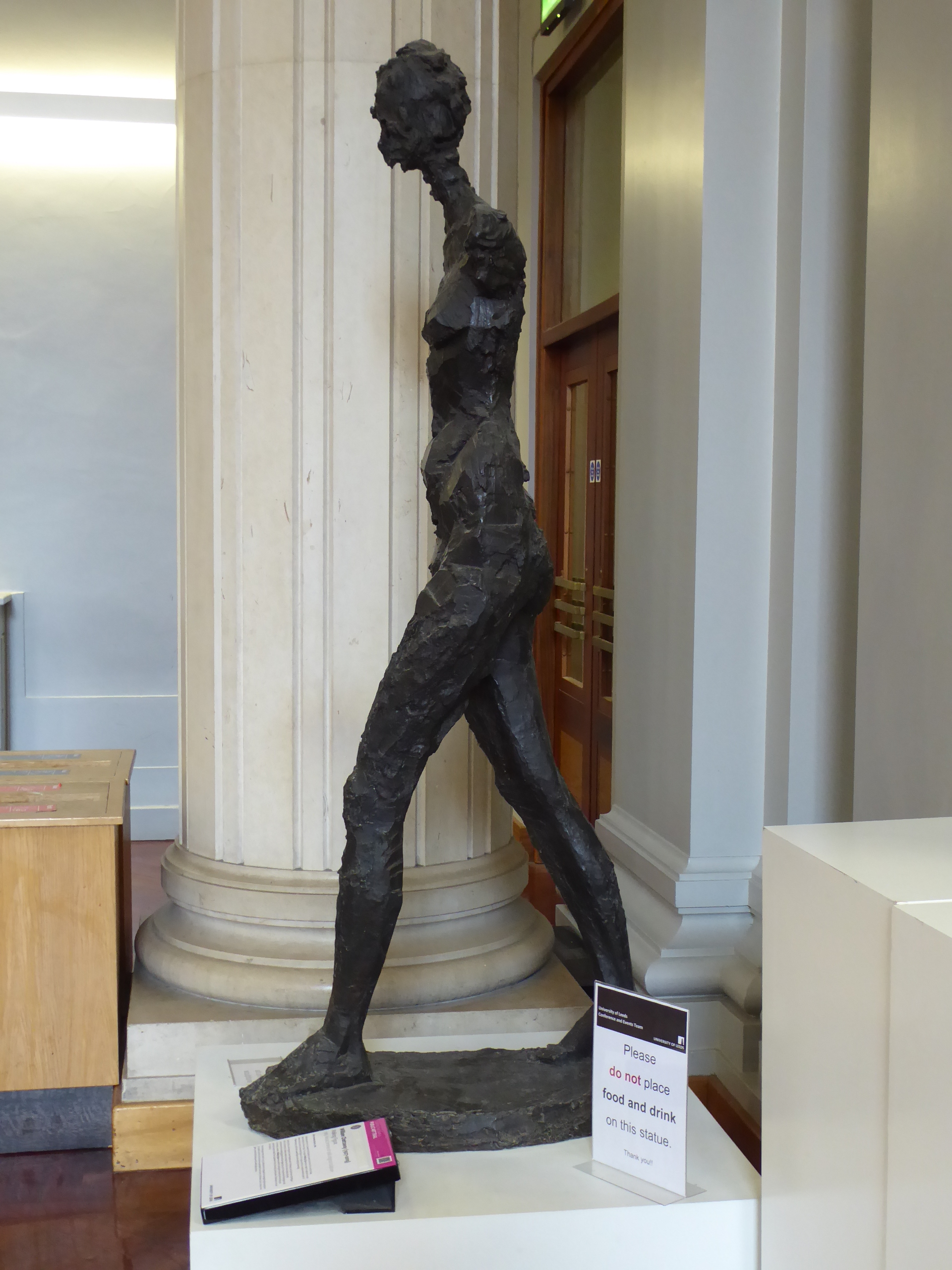

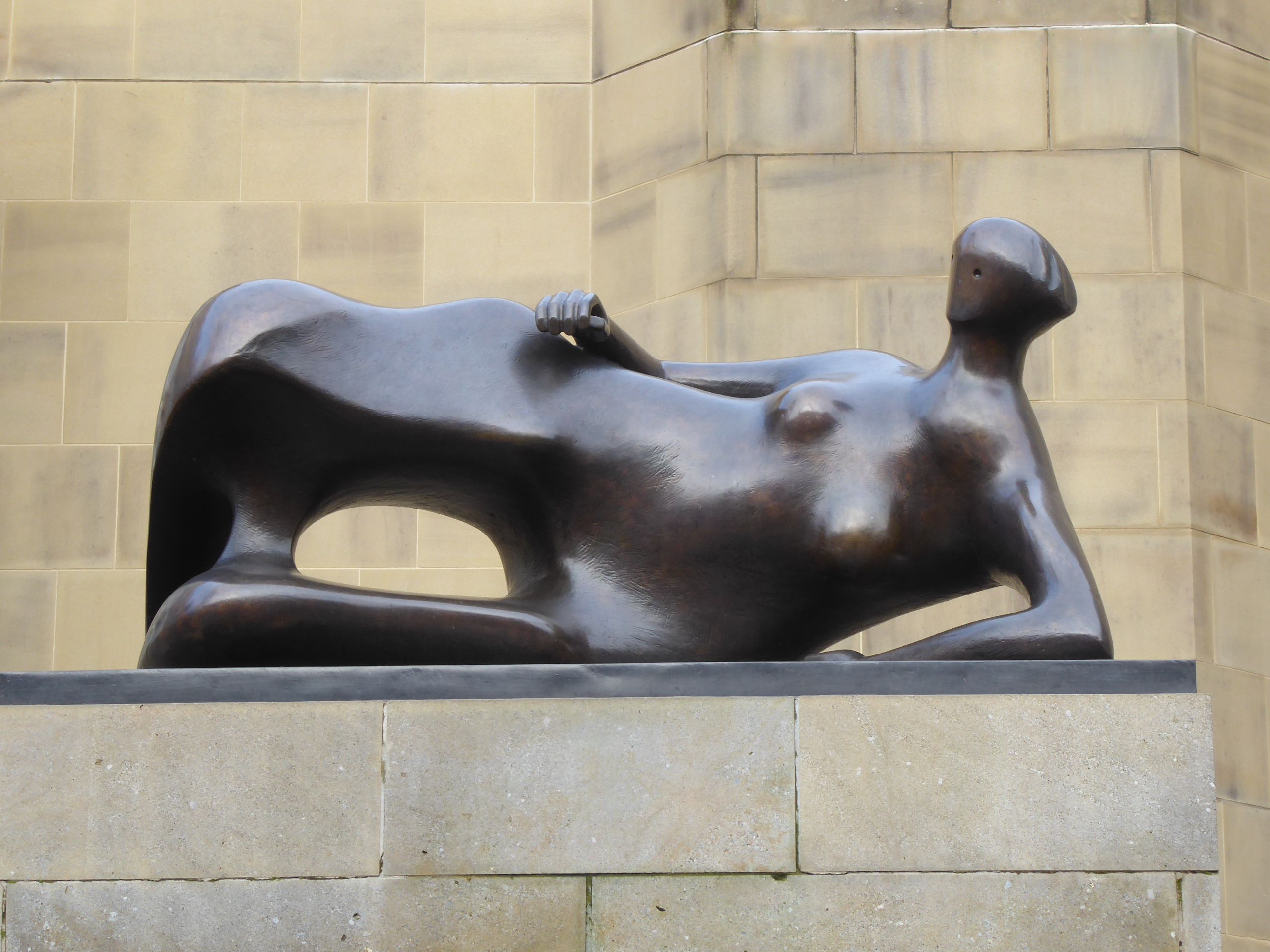

Over Christmas I’d watched Alan Bennett’s play “Sunset Across The Bay” from 1975 on BBC iPlayer. There’s a short scene of the bus passing City Square and the old man remembering when the statues were seen as “right rude”. (Heavens, how dirty the Queens Hotel was then! And the nymphs have moved around.) I’ve always rather liked the statues and I’d noticed that there were a few more barely-clothed figures around, so I looked out for them on my walk to the University.

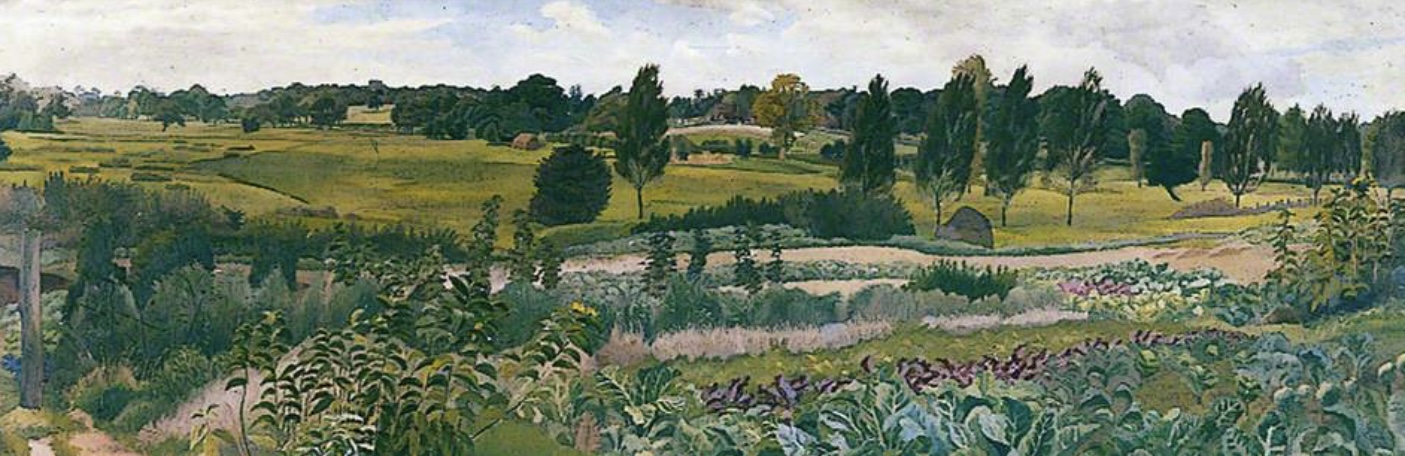

The Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery has had a change since I last visited. I was oddly taken by the work of Judith Tucker – insignificant, commonplace landscapes that are very familiar and deserve more attention. Then a painting by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham that – despite being “Untitled” – struck me (after a night at the opera) as representing three cellists. Even though I knew it wasn’t, I still stuck to it. And there was a figure by Bernard Meninsky, whom I’d come across in Hull. Not inspiring, but I can add him to my mental list. (Matthew Smith and Jacob Epstein were there too, looking very Smithy and Epsteiny.)