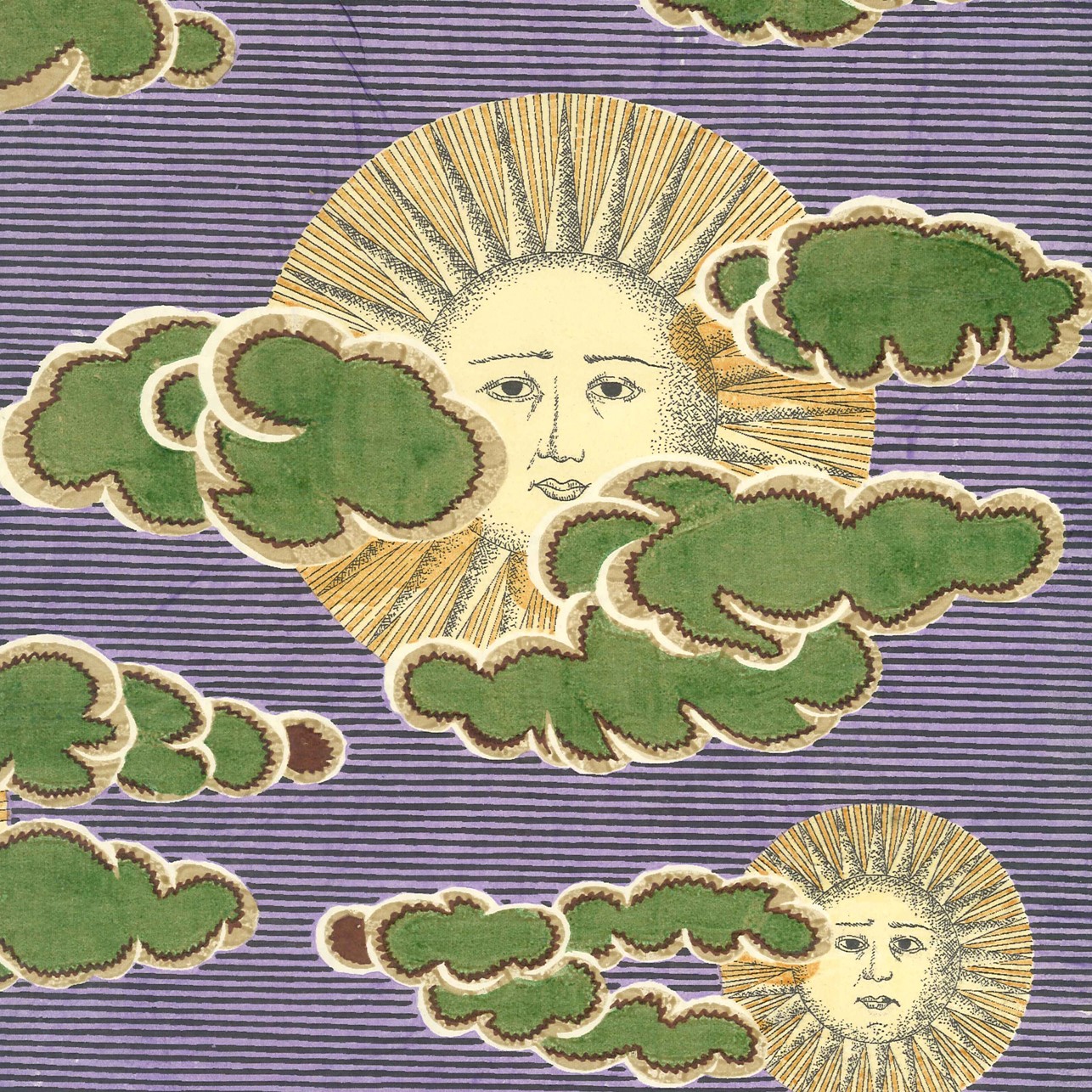

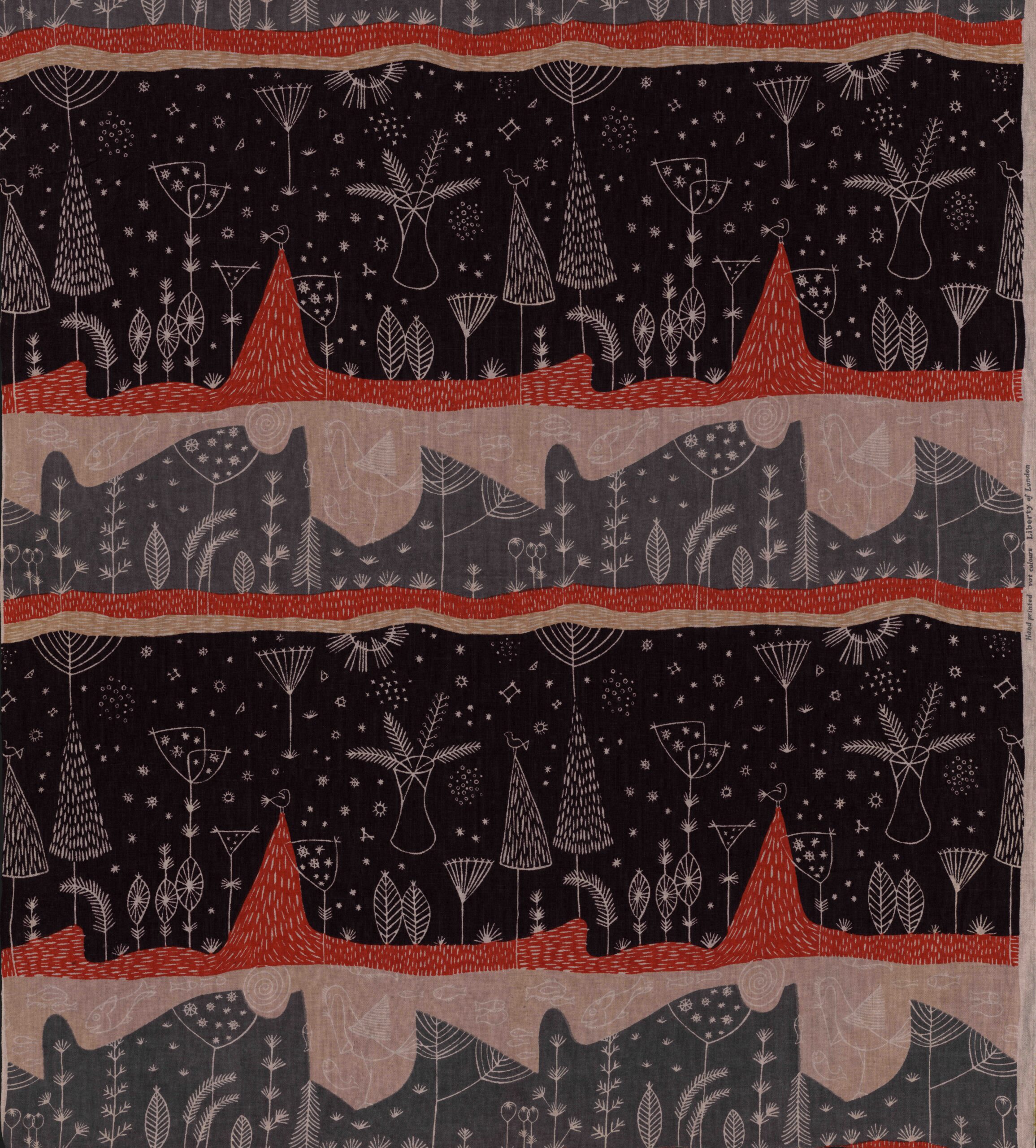

I arrived in London early and headed to Walthamstow to the William Morris Gallery for an exhibition of Liberty fabrics by women designers. There were some lovely fabrics – thankfully not all of them florals – and it was interesting to see the changing fashions over the decades. I already had a soft spot for Lucienne Day’s designs, and here I added Althea McNish, Gwenfred Jarvis, Hilda Durkin and Colleen Farr.

Arthur Liberty founded the shop in 1875, initially importing textiles and objets d’art from Asia and the Middle East. It soon moved into designing its own fabrics and helped to popularise the new Arts and Crafts and art nouveau styles. The fabrics were all printed until 1972 at the Merton Abbey Mills, and there was some fascinating film of the designs being block- or screen-printed and then rinsed in the chalk stream by men in their shirt sleeves who had been doing that work for decades. Then came the finished garment – which no doubt cost an arm and a leg to buy. A fascinating bit of social and economic history: design opportunities for talented women (initially anonymous), manufacturing work for local companies, then the sale of the finished goods to the prosperous to adorn their homes and persons – much of that exchange also transacted between women, albeit across a social divide.

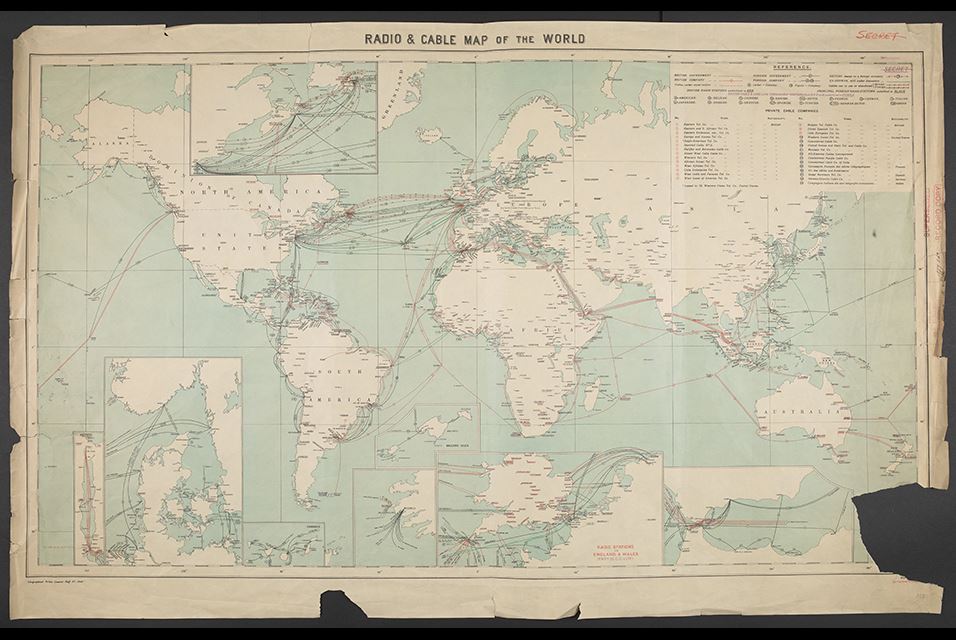

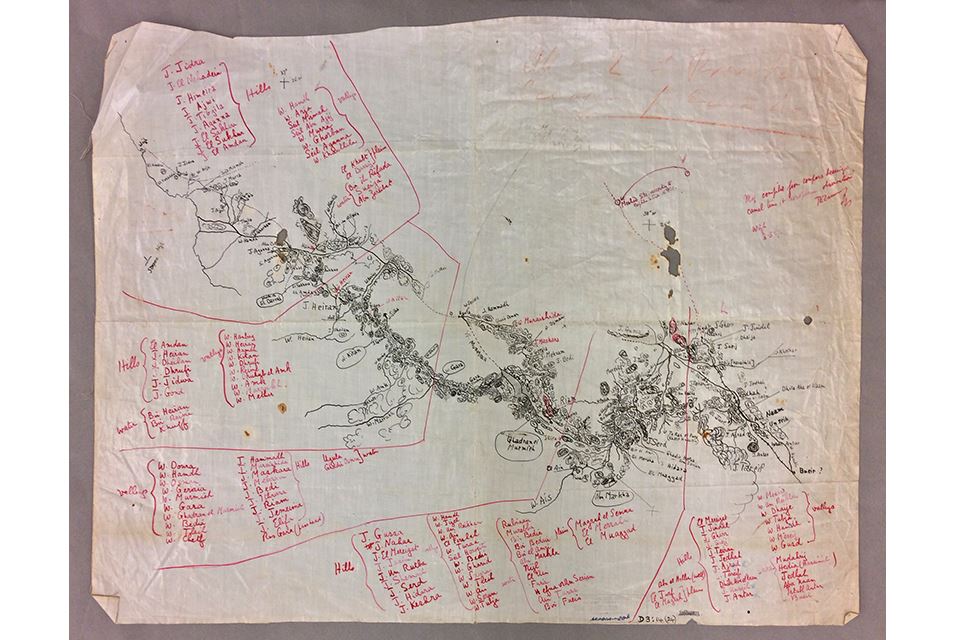

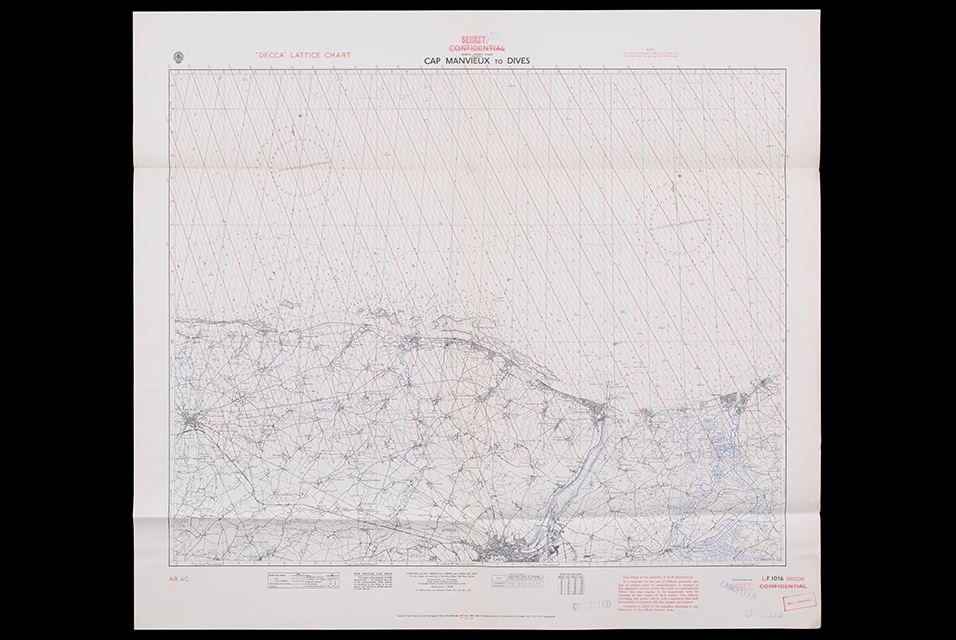

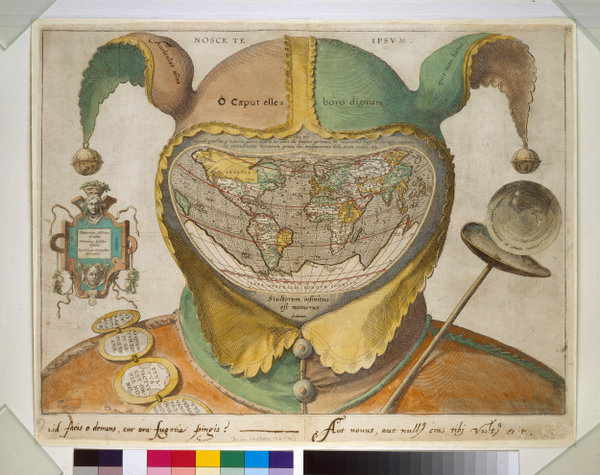

After lunch I managed to get the last ticket of the day for the Secret Maps exhibition at the British Library. (It’s the final week of the exhibition, so I was lucky.) It was good at showing the power of maps – particularly at times of war or rivalry. The Dutch East India Company tried to keep secret their world map of 1648, which showed part of the coast of Australia. Even before that, the c 1547-produced map for Henri II showed the outline of a great southern continent. Hand-drawn maps were safer, in terms of reproduction, than engraved maps. Armed or a defenceless locations could be removed from or disguised on maps (at least before aerial photography). Tiny maps or maps printed on materials like silk could be hidden (and worn). There was a wonderful hand-drawn map by T E Lawrence of his route from the Red Sea coast to the Hejaz railway. Clandestine maps of worldwide cable networks, or the chart of radio beans on the Normandy coast to assist the D-Day landings (which later influenced GPS).

The unconsidered power of maps was also revealed – as in the official map of Nairobi, which shows no sign of the vast Kibera informal settlement of perhaps 170,000 people. New rulers give new names to their colonies and territories and divide them as they wish. Certain areas/transport corridors are prioritised over others. (I note how this hierarchy is reversed when I use bike route maps: main roads are uncoloured but the route I want is a bright red line across the page.) People have not always wanted their areas to be mapped – preferring to remain under the official radar or fearing what easily accessible knowledge may bring to their land.

More personal maps: the 1930s London map which showed public toilets that were used as meeting places for gay men. Charles Booth’s 1889 map of London which marked each street on a poverty-prosperity scale. Then came GPS and all the data which can be gathered (as in the routes run by American soldiers using Strava that gave away locations of their bases in Afghanistan ) or routes that can be used by asylum seekers to cross vast distances with an encryption messaging app.

I’m glad I got the last space.