Cycling to Liverpool Street Station early this morning, I realised that the Brompton was in its natural habitat amongst its peers carrying their riders to work. But not me. I was leaving sweltering London behind to visit the Fry Gallery in Saffron Walden and its exhibition of Great Bardfield artists (Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious et al).

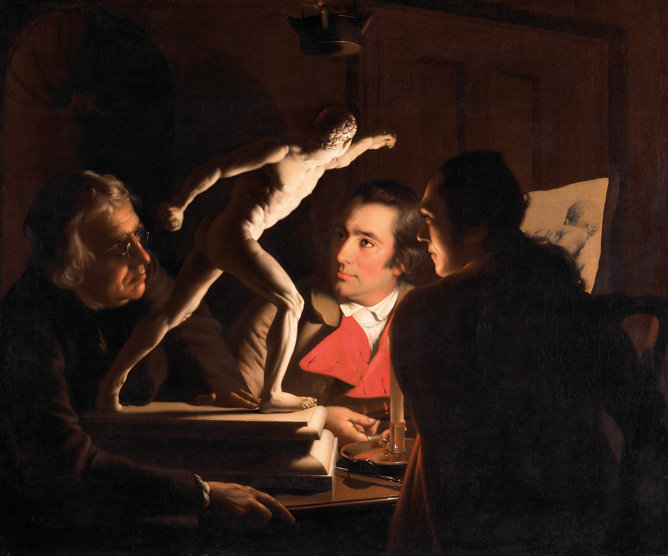

Since the gallery didn’t open until 2 p.m. I looked for something to do before that and discovered Audley End House nearby. It’s basically a Jacobean house that was once much larger and grander, built on the site of a dissolved abbey. The Duke of Suffolk embezzled state funds for it, Charles II once owned it (handy for Newmarket), John Vanbrugh and Robert Adam worked on it at various stages, Capability Brown got fired . . . the usual sort of thing. Over the centuries it has been much reduced and altered, and its current incarnation is early 19th century. So, symmetry everywhere, the deception assisted by false doors and concealed doors. A great hall with an astonishing oak screen that rises to the second floor. Family portraits everywhere plus an art collection by “follower of X” and “school of Y”. An incredible collection of taxidermy, including more kinds of owl than I knew existed and an albatross. A library that basically stored all that an English aristocrat needed to know at that time: rows and rows of records of State Trials of the late seventeenth century; antiquities of Canterbury; Dugdale’s Baronage of Englands Vol I, II etc etc – and, nice touch, a row of Walter Scott novels on an easy-to-reach shelf. The room and bed decorated specially for George III . . . who never visited. A chapel with a separate staircase and wooden seats for the servants, and a fire and padded seats/kneelers for the family. I found it fascinating and bizarre.

The parterre was lovely, and I saw it at its best. Had I not already been converted to roses, this would have done it.

Then to Saffron Walden for lunch. I ate in the main square in what I guess was once a Victorian-era bank. The great thing was that it was like a small version of Audley End: neo-Elizabethan with decorated stonework and mullioned windows, and inside I sat beneath a white ceiling plastered in Tudor style.

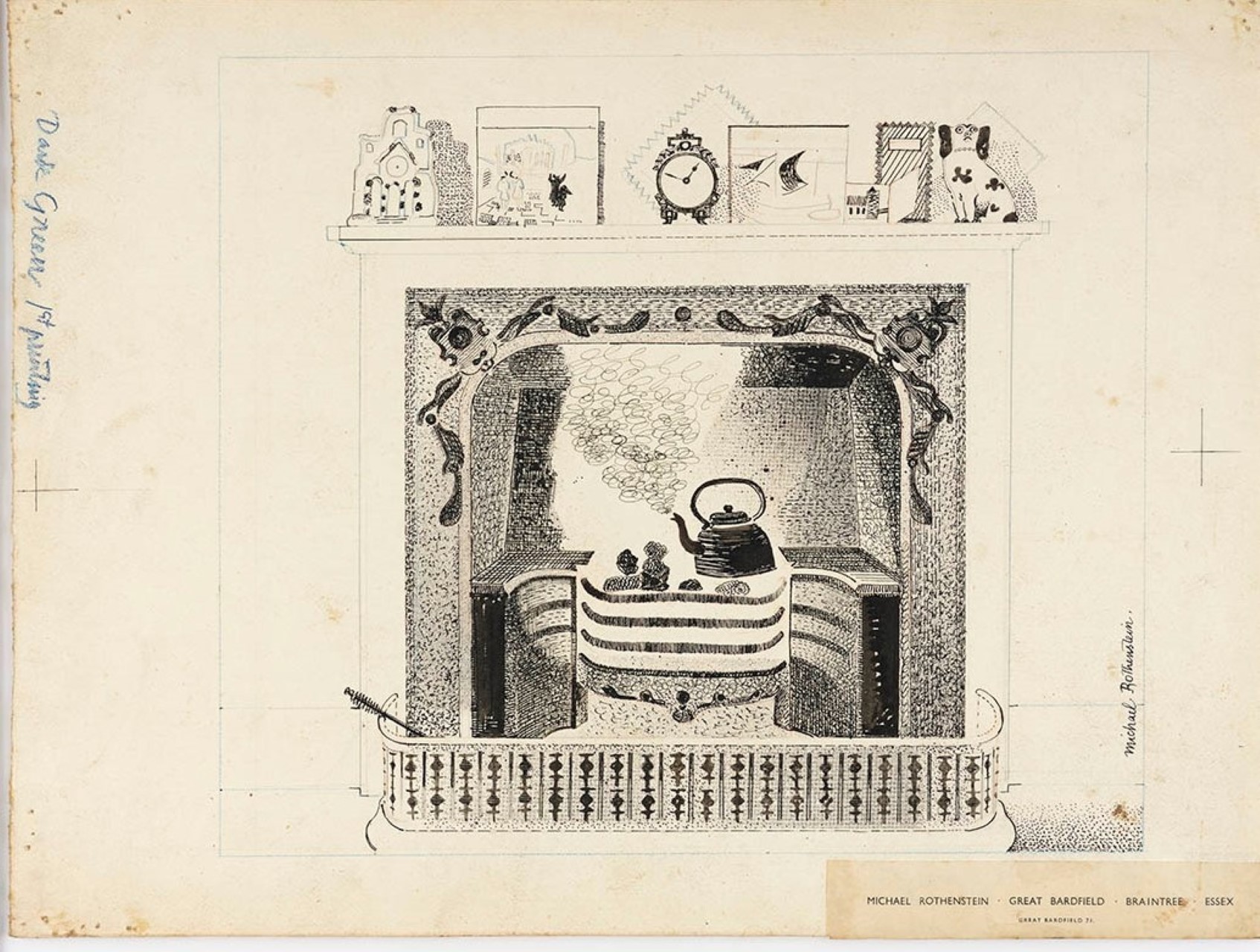

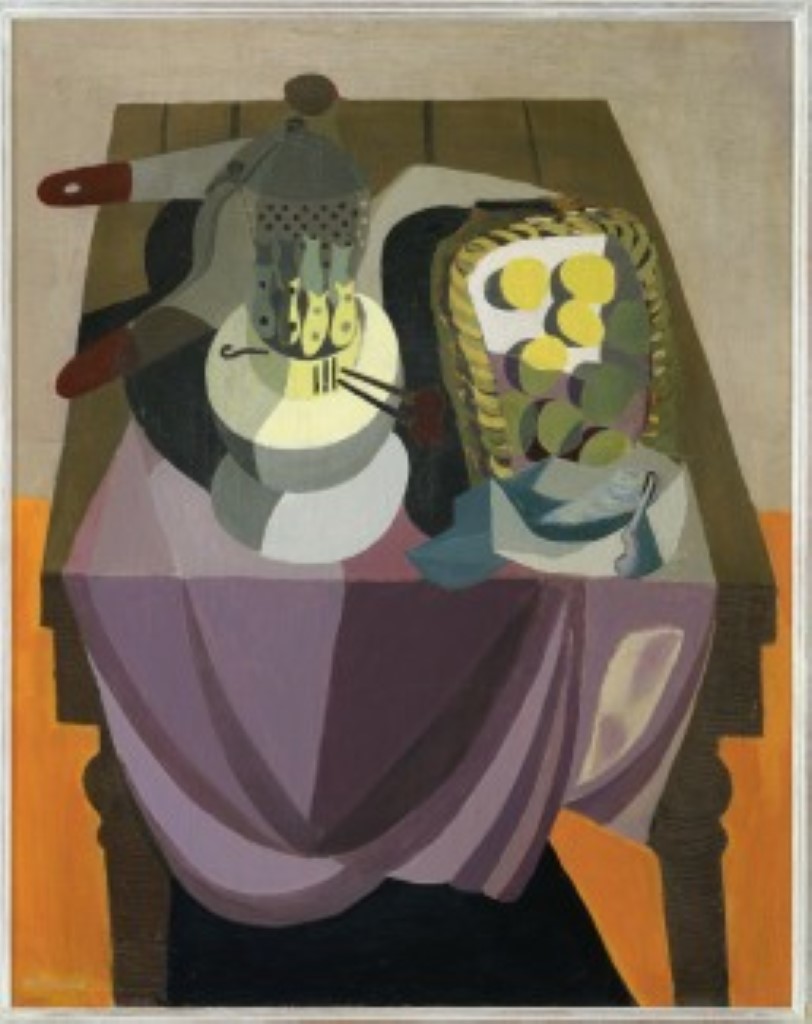

I walked past the castle to the gallery. Saffron Walden is very quaint, but with the heat and the Brompton I wasn’t in a frame of mind to take photos. The gallery is small and filled to the brim with delightful images and objects but after the space of Audley End, it seemed very cramped and the exhibits seemed cosily domestic.