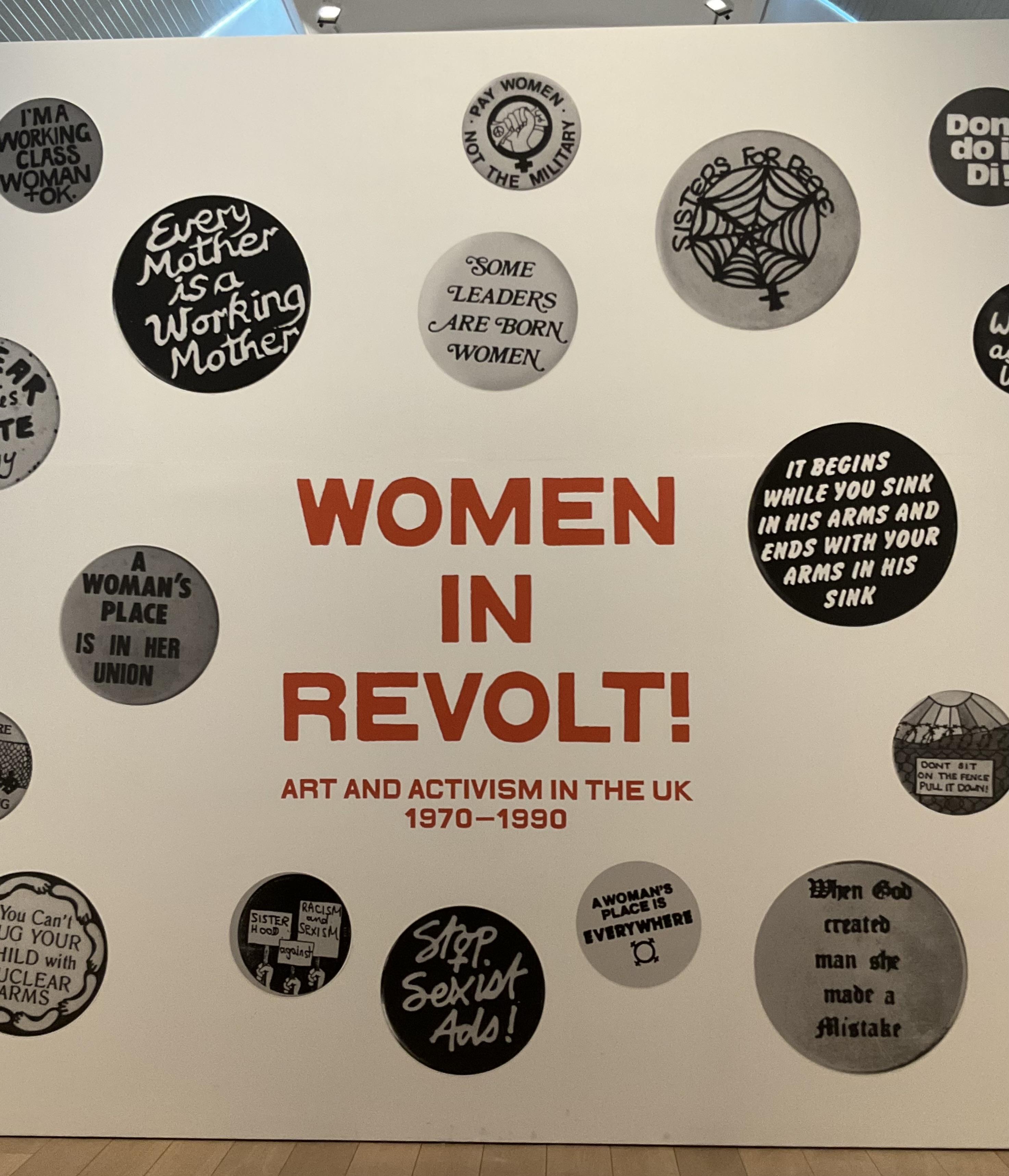

I was in Manchester for the day and went to the Whitworth Gallery and thus saw two contrasting exhibitions. One was Women in Revolt, which I found interesting – probably not entirely for the expected reasons. Since I do recall the 1970s and 1980s, many of the events and social attitudes were familiar to me. The artwork was punchy rather than classy – reflecting the anger of that time and the everyday media that the artists/activists used (e.g. collage, fabric). At this remove it’s easy to forget how outlandish some of the demands for female equality seemed at the time to “ordinary people” – equal pay, professional opportunities, childcare, the assumption of being taken seriously. My aunts, for example, were ambivalent to, if not dismissive of, female equality. How far we have come! No, what did catch my attention was a film of ordinary women in the street, accosted by a male television journalist and asked what problems they encountered as women in the 1970s. It was almost a Socratic dialogue: he hectoring and various shes pondering his questions, totally media-unsavvy, and giving hesitant answers about things they perhaps hadn’t considered before. There was a polite bewilderment at being asked to examine their lives, rather than the redundant-heavy easy flow of words that a vox pop today might elicit. The exhibition assumed a natural relationship between 1970s feminism and other progressive attitudes – the relationship not embraced by women in power at that time like Margaret Thatcher.

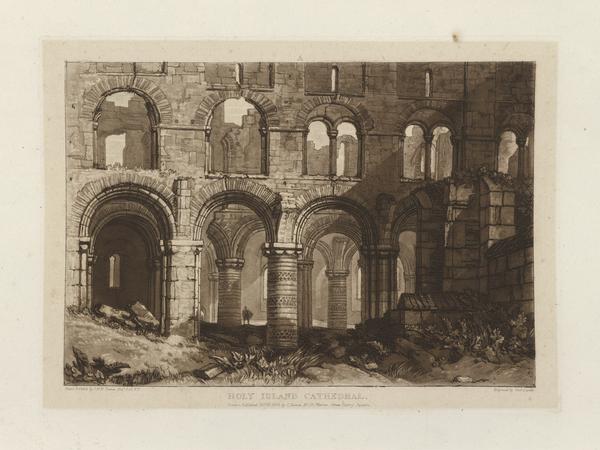

And then Turner’s prints. The Whitworth had emptied all its shelves and backs of cupboards for this. They were rather lovely, and I was impressed by the quality of the mezzotints. A very different experience.