I was hurrying back to the station after a late lunch and noticed the Christmas tree and lights and the way the office block resembled an open advent calendar so I had to stop. It’s bizarre really: midwinter on Midsummer Boulevard.

I was hurrying back to the station after a late lunch and noticed the Christmas tree and lights and the way the office block resembled an open advent calendar so I had to stop. It’s bizarre really: midwinter on Midsummer Boulevard.

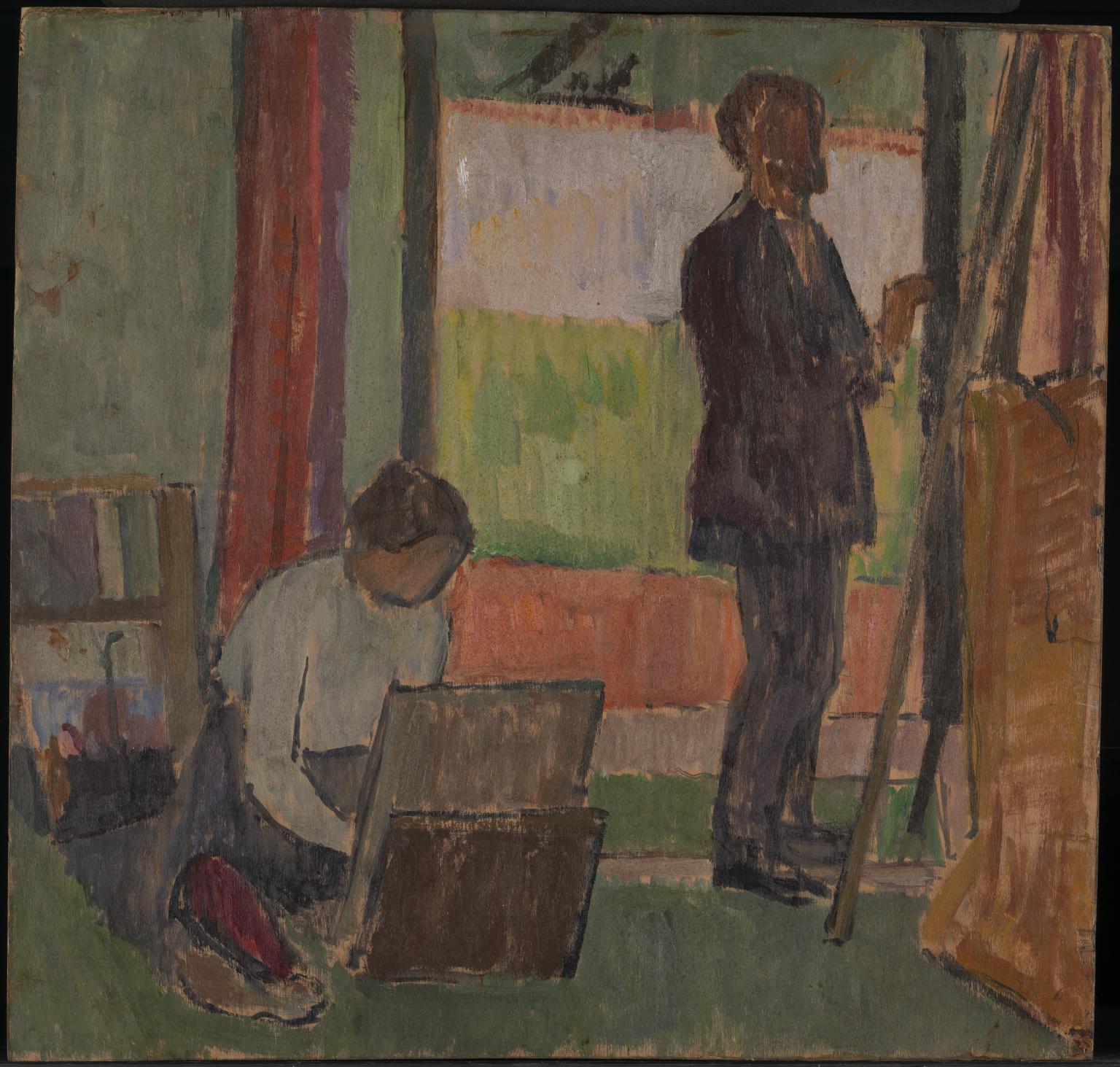

To the Vanessa Bell exhibition in Milton Keynes to see if I could feel more positive about her work. Well, not really – but the journey to that decision was quite interesting.

I’d been to the same gallery to see Laura Knight (1877-1970; Bell 1879-1961) and it was instructive to compare the two exhibitions and artists. Knight’s work (as curated for the exhibition) followed a path from early experimentation to a recognisable style and regular themes; she had to earn her living from an early age and she was sometimes hard up. She accepted commissions, she worked as a war artist, she designed decorative work. She was married to the same man for decades and had no children. In short – at least outwardly – a fairly tidy story of a groundbreaking woman artist and her body of work.

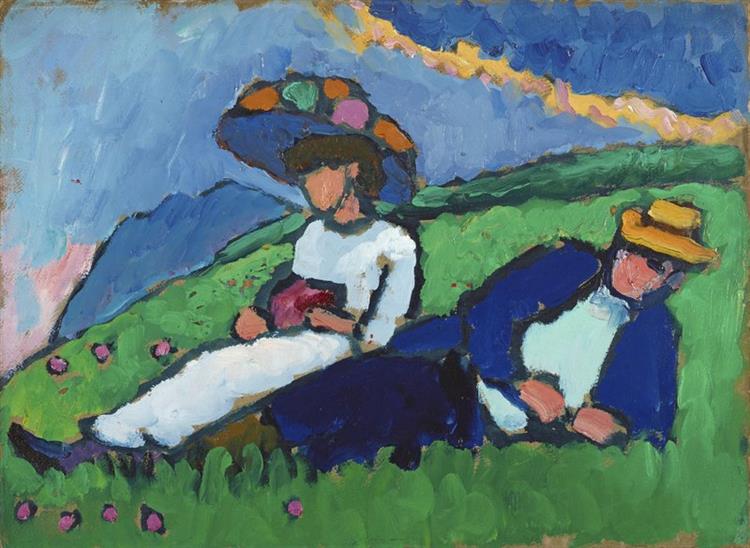

Bell, in contrast, seemed all over the place. She was more experimental (personally and professionally) and her focus was on the “language” of form and colour – but I really couldn’t find a single piece that stopped me in my tracks or pleased me entirely. I had thought of her colour palette as rather murky and muddy, but here there were brighter colours that I hadn’t expected. Nevertheless much seemed slightly unfinished or unthought-through. Her portrait of her sister, Virginia Woolf, was up there with Cassandra Austen’s of Jane: affection but not execution. Whenever something caught my eye, I found myself thinking that someone else had done it better. A painting of the Etchell siblings with featureless faces, for example: it paled beside Gabriele Münter or Roger Fry and looked slightly inept.

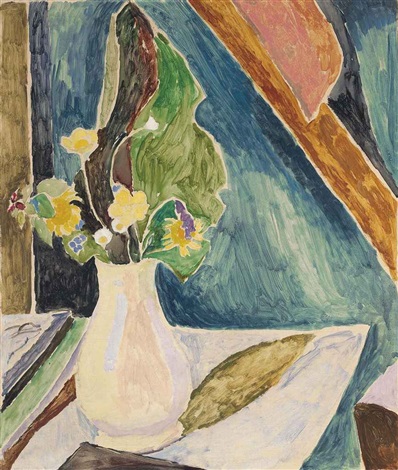

I went with a companion, who got quite irritated with a pair of still lifes. The lack of focus: was it form or colour in the wildflowers? Why did one think of felt-tip pens running out of colour? Why the silly cross-hatching on the vase in the more accomplished lilies?

One answer is that Bell did what she liked. For all her involvement with the Omega Workshops, Bell didn’t have to earn her living by her work, and she had help in bringing up her three children. She also ditched conventional morality. And I think this was the one really great thing about her – she had the chance of freedom and she really went for it. The decorations in their Charleston home, the foregrounding of women’s lives, the collaboration with others, the refusal to be confined by one style or theme, the unconventional way of life – that was what was interesting.

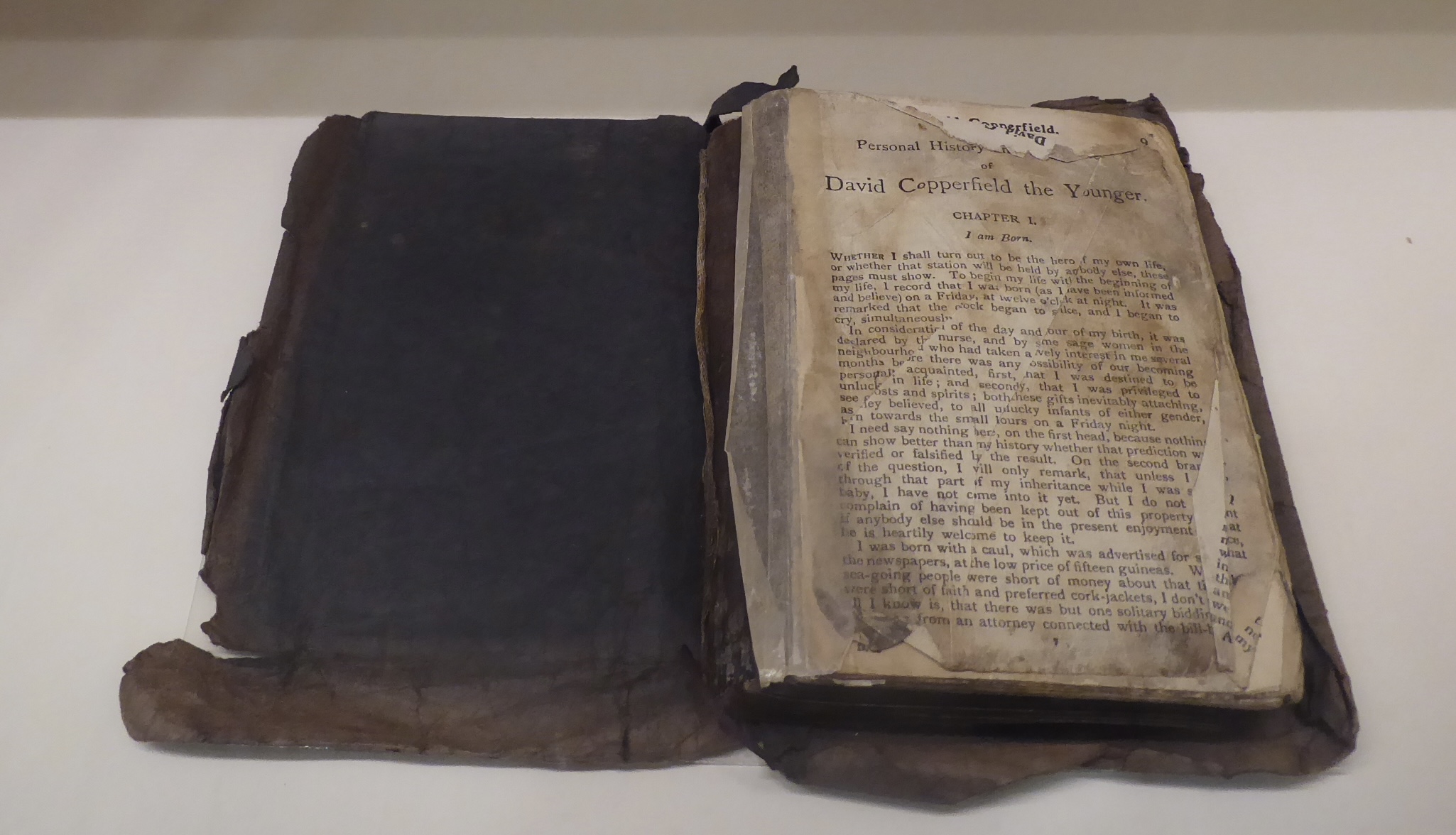

I returned to London and a much more conventional and masculine – even macho – experience. I just had time to get to the Charles Dickens Museum to see the copy of David Copperfield that had gone to Antarctica on the Terra Nova expedition. I had to see it. Edward Wilson, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, Herbert Ponting . . . the fascination I experienced when I first read Wilson’s diaries briefly returned as I looked at the blackened, dog-eared pages. And it was a lovely sky as I walked back through St George’s Gardens: perhaps I can compare this afternoon’s moon with Cassini’s map!