What prompted me to come to Newcastle this time was the re-opening to passenger traffic of the railway line to Ashington – which is the gateway, for me, to see the works of the Pitmen Painters.

The Brompton and I found the cycle path from Ashington to the Woodhorn Museum. In addition to the gallery, it’s also a mining museum in what was, until 1981, the Woodhorn Colliery. There was once also an Ashington Colliery – a distance that it had taken me ten minutes to cycle slowly – so, of course, I started wondering how cheek-by-jowl collieries were here and found a 1951 map online which gives me an answer. From the train I’d seen a few old spoil heaps, just humps and plains covered by scrubby vegetation, but, as an outsider, I find it hard to imagine what this area was like until fairly recently. The museum is interesting: several of the key buildings remain, along with the pit wheels, and I noted (as with old German mining administration blocks) that even functional buildings can include proportion and decorative elements.

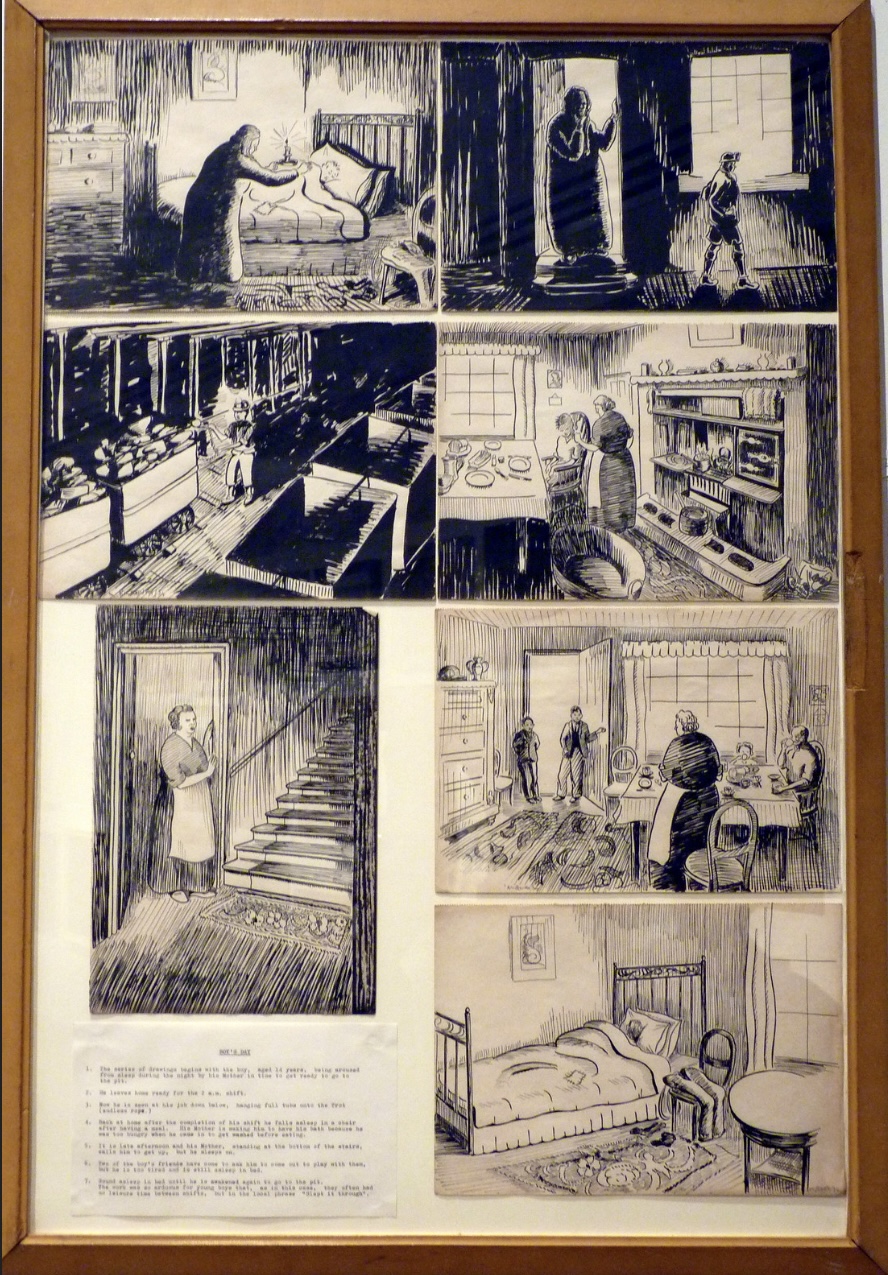

And so to the Pitmen Painters. In 1934 a group of miners, having finished one WEA course, began another on art appreciation under their tutor, Robert Lyon from Armstrong College, Newcastle. (Is that the Cragside and Bamburgh Castle Armstrong?) Lyon considered that his students would learn to appreciate art more effectively by doing it themselves – and so an art group was established in Ashington. They met regularly for fifty years and painted together – mostly scenes from their lives. Their materials were what they could afford, and initially it was Walpamur decorating paint on plywood. I felt rather mean as I reflected that their skills had not developed markedly over the years, but actually I was misreading their work. It was art rooted in their community, from a communal age and a particularly close-knit industry. I had a fleeting sense of recognition as I looked at the paintings – something that took me back to my grandparents – and an awareness of their rootedness. Which I suppose is another word for authenticity.

I had decided that I would have a little ride and return to Ashington railway station; the barrier of the River Wansbeck made a ride south look unattractive, so I decided on a little ride north – just a few miles and then turn round. Only the wind was at my back, the weather was so pleasant and the road so quiet that I just kept pedalling, past Druridge Bay, past Amble, past Warkworth Castle . . . until I ended up at Alnmouth once again. I haven’t been there for over twenty years – and now I’ve been there twice in two days.