The coach drove us through chocolate-box England to an inn beside a chalk stream for lunch and then on to Salisbury: hollyhocks and thatched roofs en route to an Early English Gothic cathedral that has been on my “to visit” list for years. What could be nicer?

Our destination was the Wessex Galleries of the Salisbury Museum: more artefacts from under the ground. As a devourer of detective stories, I likened them to a traditional country house murder: clues and red herrings throughout but no big dénouement in the drawing room to give the single correct account. Archaeologists are scientists, not Hercule Poirot: they offered possible explanations but then offered an alternative. Thus the grave of the Amesbury Archer: he was not from Amesbury and he may not have been an archer. He grew up in central Europe and had a limp: the arrowhead buried with him might be the red herring which has given him his name, and the portable anvil, perhaps marking him as an early metalworker, might be the real clue.

Yet another significant amateur archaeologist’s name to remember (if not necessarily in the correct order): Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers, who excavated with great method and founded a couple of museums.

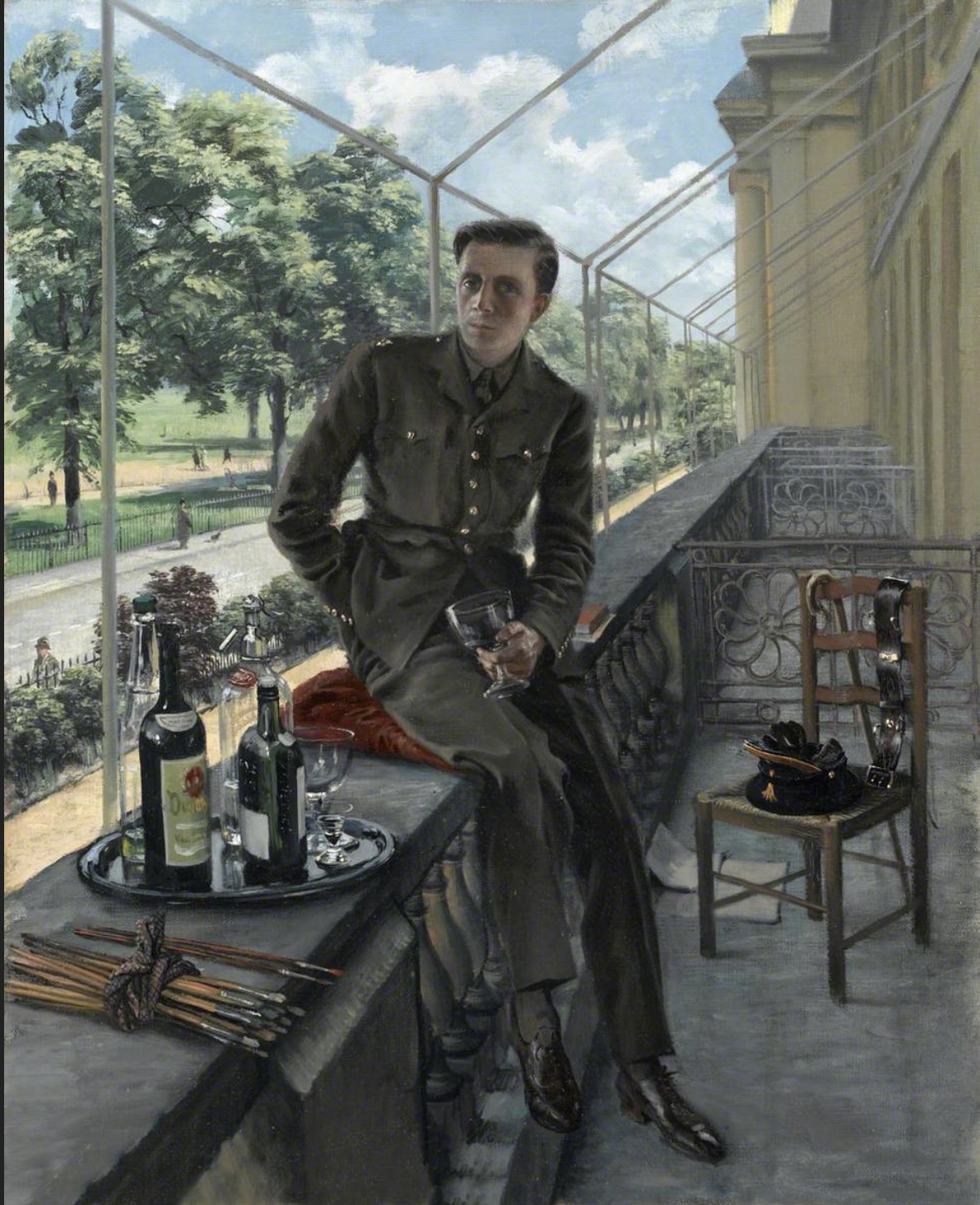

I fast-forwarded to the twentieth century with the museum’s small exhibition on Rex Whistler. I’d come across him in the Tate restaurant and at Haddon Hall. Whistler had a gift for befriending wealthy people, who then commissioned his murals. Everything was lightweight and frivolous – the stage designs, portraits of his friends against their country houses, even his 1940 self-portrait looking very relaxed and debonair in his brand-new Welsh Guards uniform. But he had volunteered, not been conscripted; he became a tank commander and was killed in action in 1944. With that snuffing out of the “bright young thing”, I had to re-adjust my ideas. Lightweight, frivolous and brave.

Then to Old Sarum. Formerly a complete town, formerly a rotten borough, now just a ruined castle on a mound and the outline of a very small cathedral that was left when the clergy, fed up with the army and the administration, picked up their skirts and headed down to the water meadows to found the new town.