A waking nightmare: a young mother suffering from TB falls asleep on a day bed and awakes to find herself on the same bed and in the same condition but in another body and another time. The themes of illness, death, frailty, constriction and loss of identity are unnerving. The short novel follows Melanie as she realises what is happening to her – her fear, her attempts at rationalising, her horror as hope of escape or return fades. She is aware of being both herself, Melanie, and the person whose body she inhabits, Milly, whom she begins to understand:

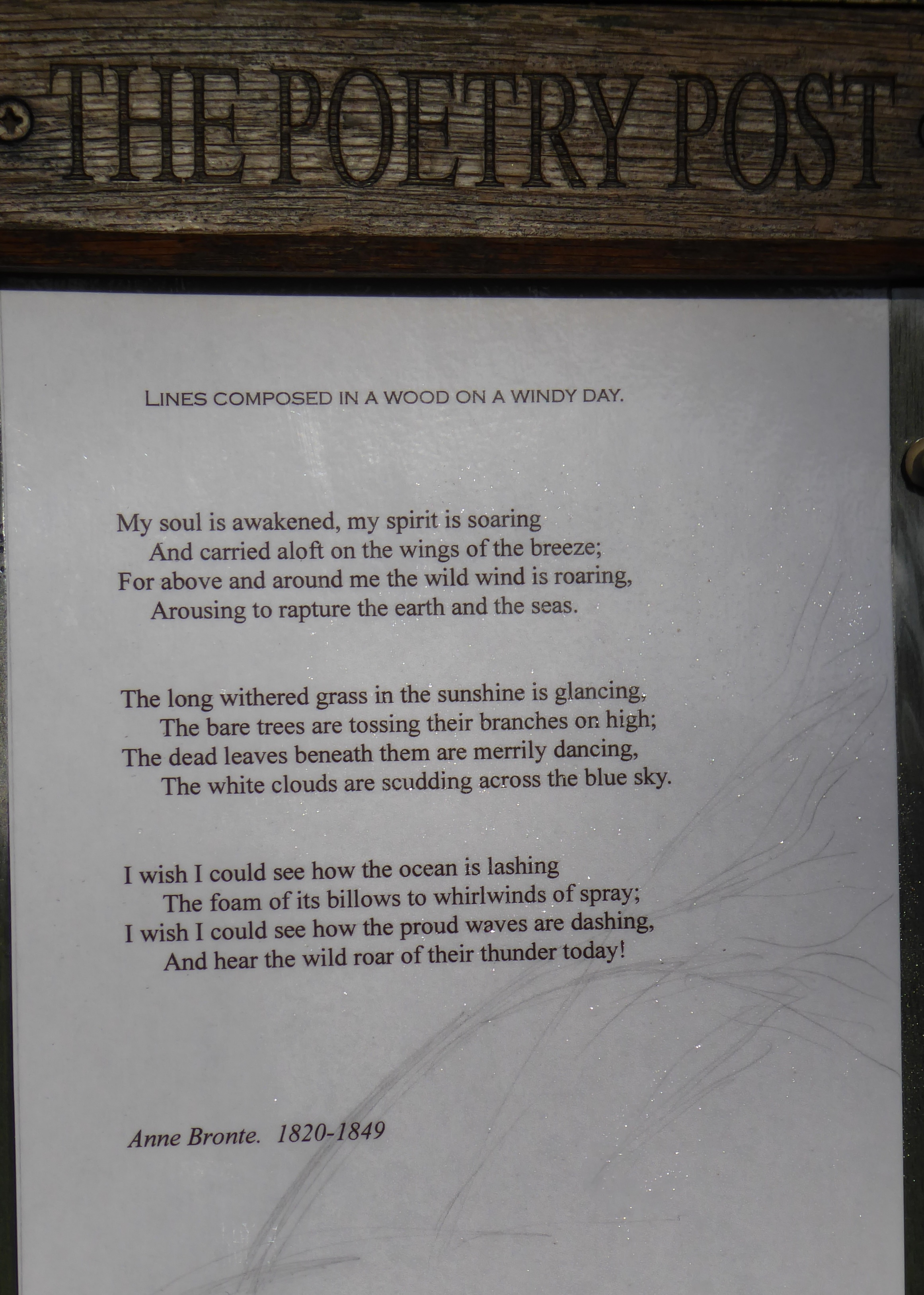

I think we did the same things, she told her, we loved a man and we flirted and we took little drinks, but when I did those things there was nothing wrong, and for you it was terrible punishable sin. It was no sin for Melanie, she explained carefully, because the customs were different; sin changes, you know, like fashion.

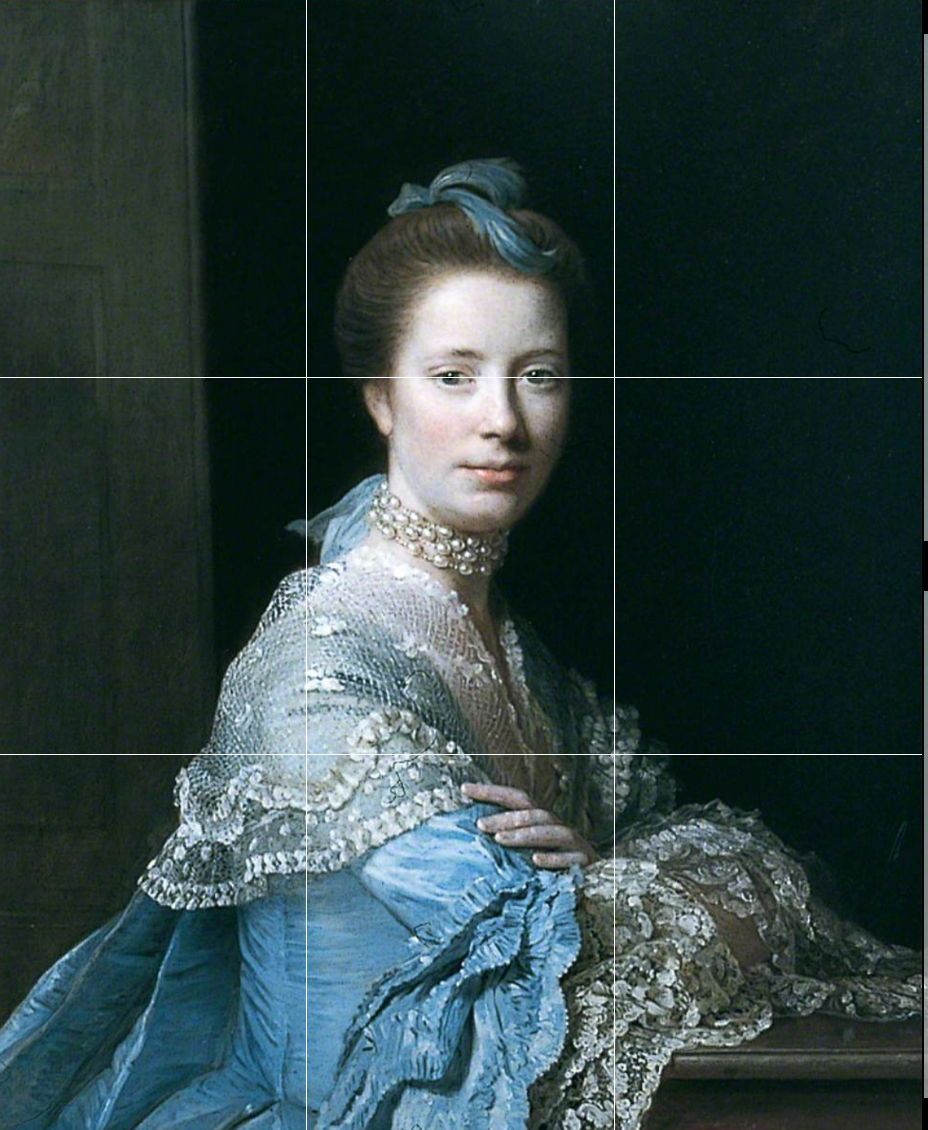

The chaise-longue as a Procrustean bed that cuts women down to helpless femininity? Or a gin-trap for women who are not on the alert to their vulnerabilities in the outside world? There are parallels in the women’s lives across the distance: both have experienced sexual passion – the words used are “rapture” and “ecstasy”, which both imply something out-of-body – outside/before marriage, and both have been weakened by their pregnancies. Milly’s life is a dark version of Melanie’s: in place of a loving (but straying?) husband and a fond doctor, Milly has a lover who cannot marry her and a doctor who resents his thwarted passion for her. Instead of Melanie’s sensible professional nurse, Milly has her stern sister. Melanie’s TB may be curable in the 1950s; Milly’s, in the nineteenth century, will literally be the death of her. Suburban Gothic horror.