The Christmas Fair is in town; I blanked it . . . until the moment I saw the big wheel in Albert Square. No hesitation.

The Christmas Fair is in town; I blanked it . . . until the moment I saw the big wheel in Albert Square. No hesitation.

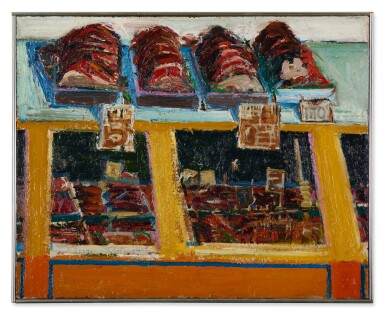

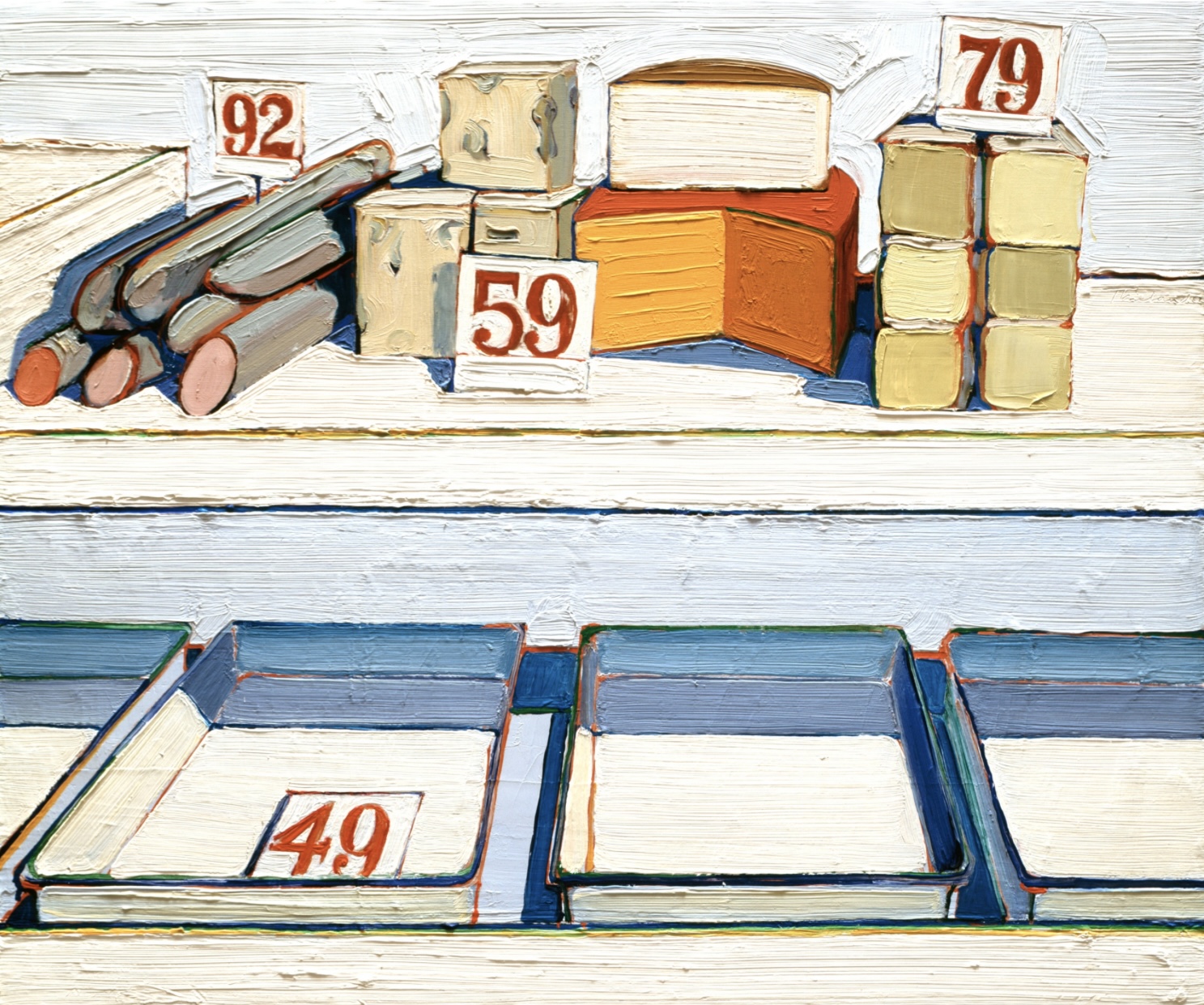

Each era produces its own still life

Sometimes I am not sure what will grab me and what will elude me. I quite like being surprised by myself. And – for some reason – this small exhibition of a particular section of Thiebaud’s work grabbed me. The introductory panel with Thiebaud’s own quotation set me up: I couldn’t deny what he said, and it was enough to open my mind to his work. Without it I could just as easily have come away thinking that, like Lichtenstein, he had found his schtick and stuck to it. The exhibition reminded me of a book I had to read (“plough through”) for an OU course: Gombrich on the beholder’s share when looking at a work of art. It made sense in front of Thiebaud.

As a graphic artist, he knew how to make an impression. Things I noted:

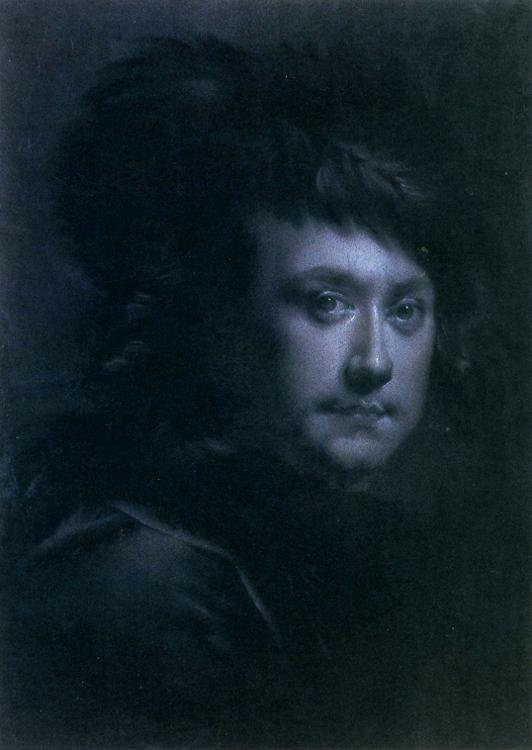

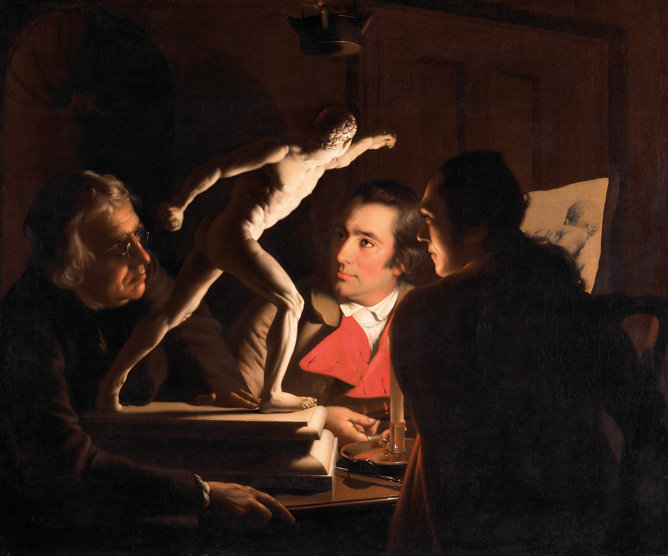

After two exhibitions in one afternoon, I thought that what Joseph Wright of Derby (the “of Derby” to distinguish him at that time from another painter of the same name) and Cecil Beaton had in common was creating their own distinctive worlds. One serious and one frivolous. The Wright exhibition was small, containing only a few large canvasses (but what canvasses!), some mezzotints (Wright had an eye for wider consumption), a couple of related exhibits (e.g. an air pump and an orrery) and a rather wonderful self-portrait in pastel. I had thought of him as painter of the new “scientific” age – casting new discoveries in a mould usually reserved for the heroic or biblical – but his range was broader than that. There were little tics: hidden light sources, glowing red tones. He certainly casts J Atkinson Grimshaw into the shade.

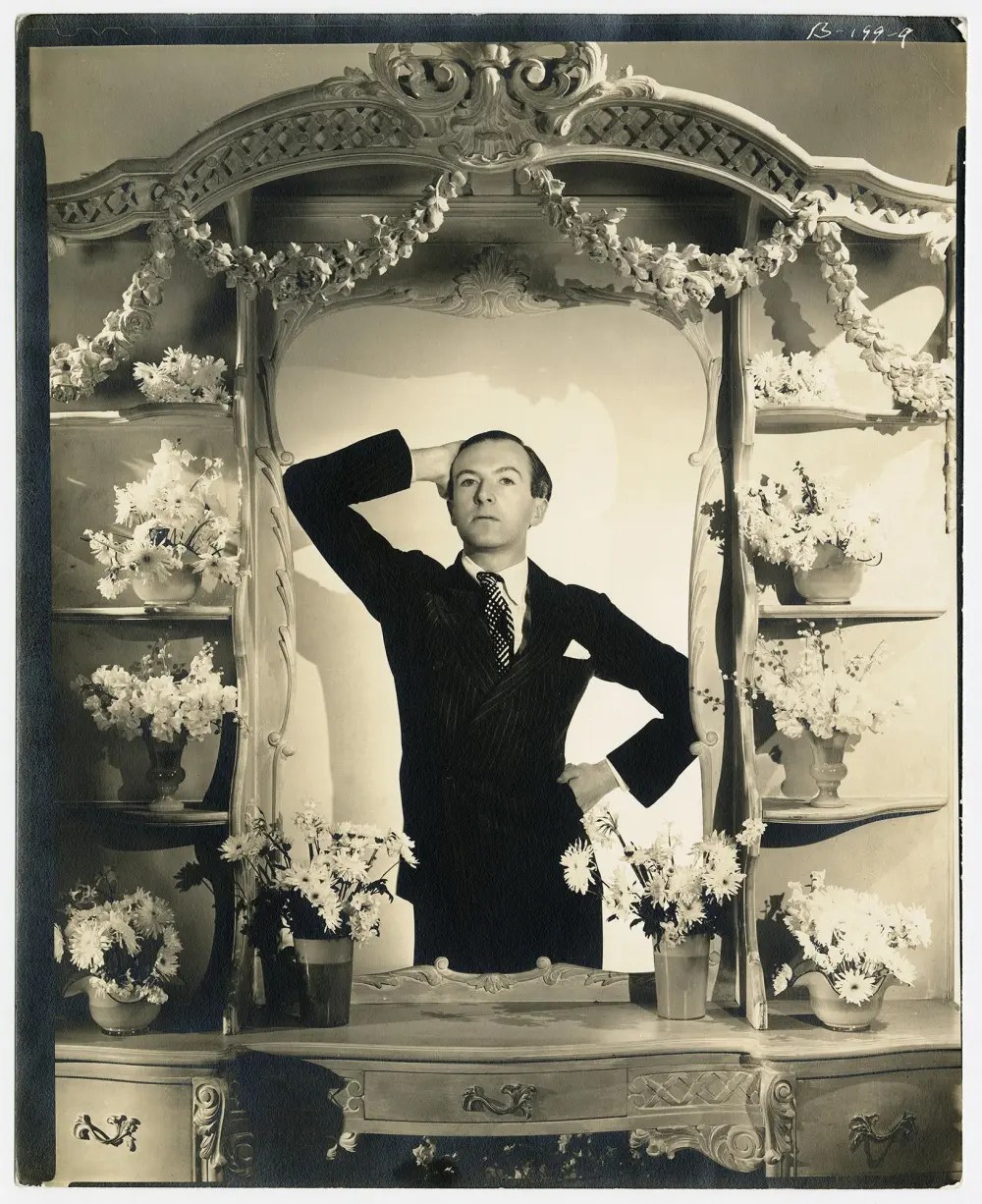

And then Cecil Beaton. The Wright exhibition was compact, and the Beaton one would have benefited from the same treatment. At times it felt like one perfect epicene profile and slicked-down hairstyle after another: the appeal of glamour (which is great) had dwindled to a yawn by the final rooms. His photographs, though – like Wright’s painting – do conjure up their own world, a mix of Brideshead Revisited and Hollywood floating in an atmosphere of superficiality and what would now come across as snobbery. There was the hiatus of WWII in all this gaiety; it killed Rex Whistler, Beaton’s friend, and sent Beaton around the UK and the world for the Ministry of Information. The Royal Family, Vogue, theatrical design . . . ah, good, the exit.

But it did send me up to room 24 afterwards to look at Augustus John’s portrait of Lady Ottoline Morrell, described by Beaton as presenting her with magenta hair and fangs. And it does!

The Harris in Preston has recently re-opened after being closed for some years for renovation. It’s a building with more than one function – art gallery, museum, library, café – and the divisions between them have been blurred in its new layout. Hence there are paintings and reference books amongst desks and chairs in a grand room that rather made me wish I had some school homework to do. Its exhibits are more varied than before, making an effort to reflect Preston from Victorian times to the present day. I definitely want to return and wander at will again.

I may transfer my loyalty from the Grand in Leeds to the Theatre Royal in Newcastle. My first visit, and I was so pleased to have a clear view of the orchestra (including theorbo) from the dress circle.

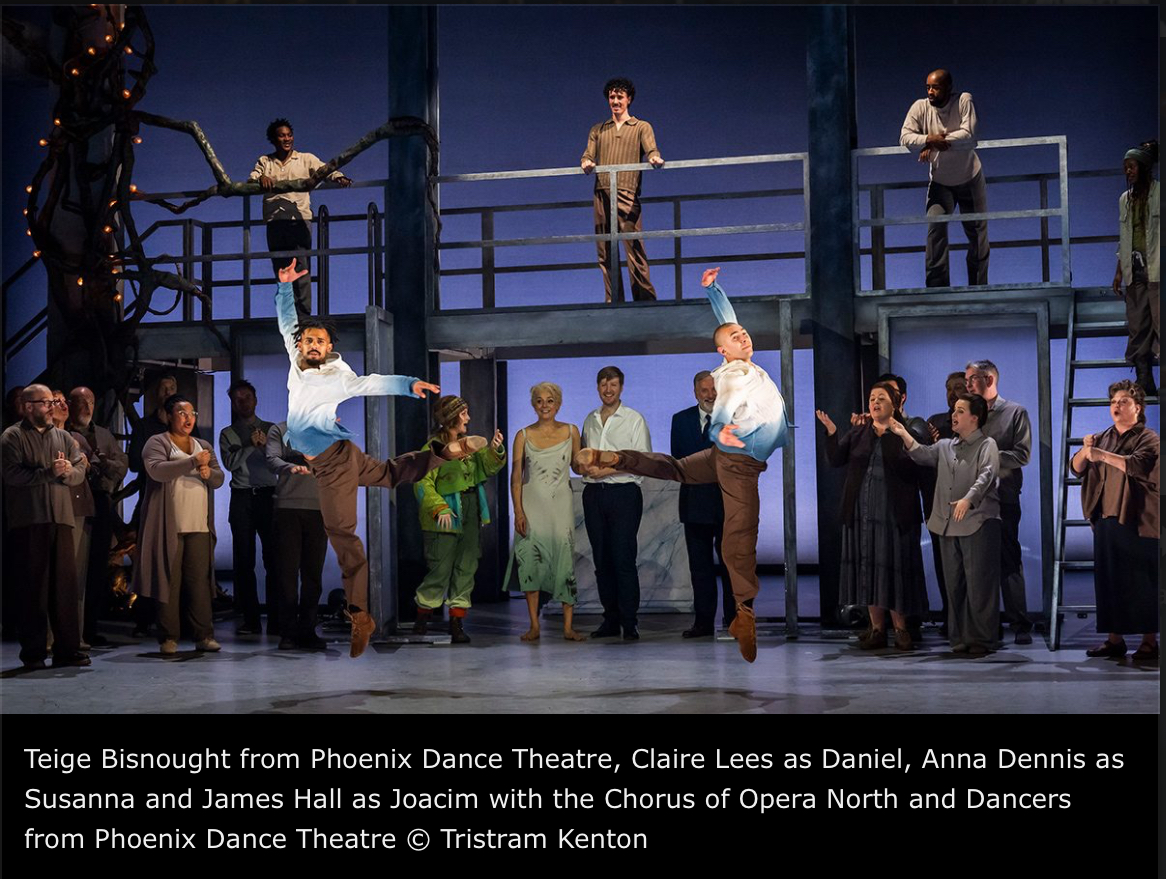

This was a collaboration between Opera North and the Phoenix Dance Theatre: contemporary dance meets Handel’s oratorio. Sometimes it worked – dancers expressing the latent sensuality of the libretto. On the whole, though, it didn’t gel for me – and I’m willing to admit the deficiency is probably in me rather than the production. It crowded the stage, particularly with the chorus present. BSL was also included – partly in occasional gestures of the chorus, but most obviously through the presence on stage of a BSL interpreter, who made me think of someone who’d wandered on from the wings and decided to stay. I reminded myself – once again – that if I can swallow traditional opera with all its absurdities, I can’t baulk at innovation.

The singing and acting were wonderful. The moment the chorus began their lament for their exile in Babylon, I could feel a lump in my throat. Susanna and Joacim (a counter-tenor) were brilliant, as was the production.

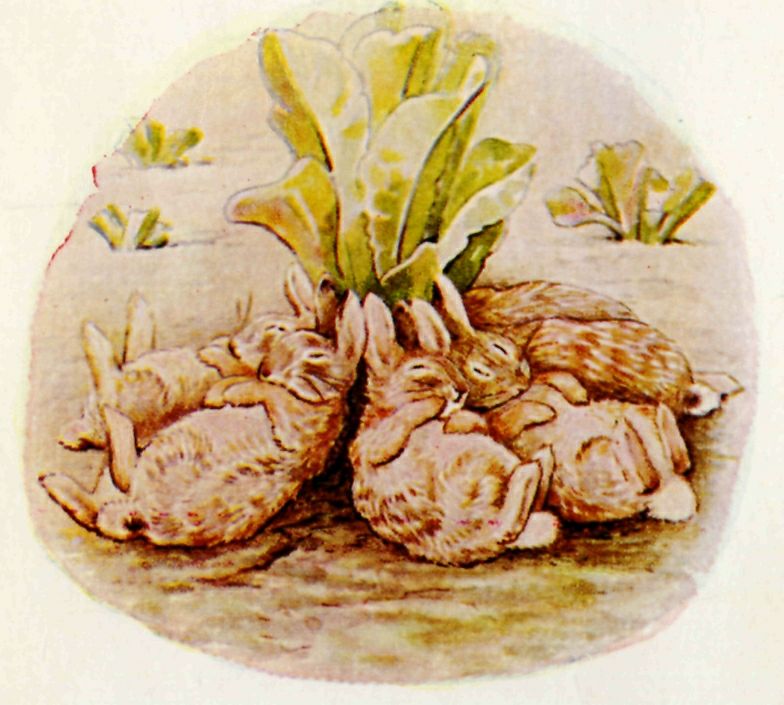

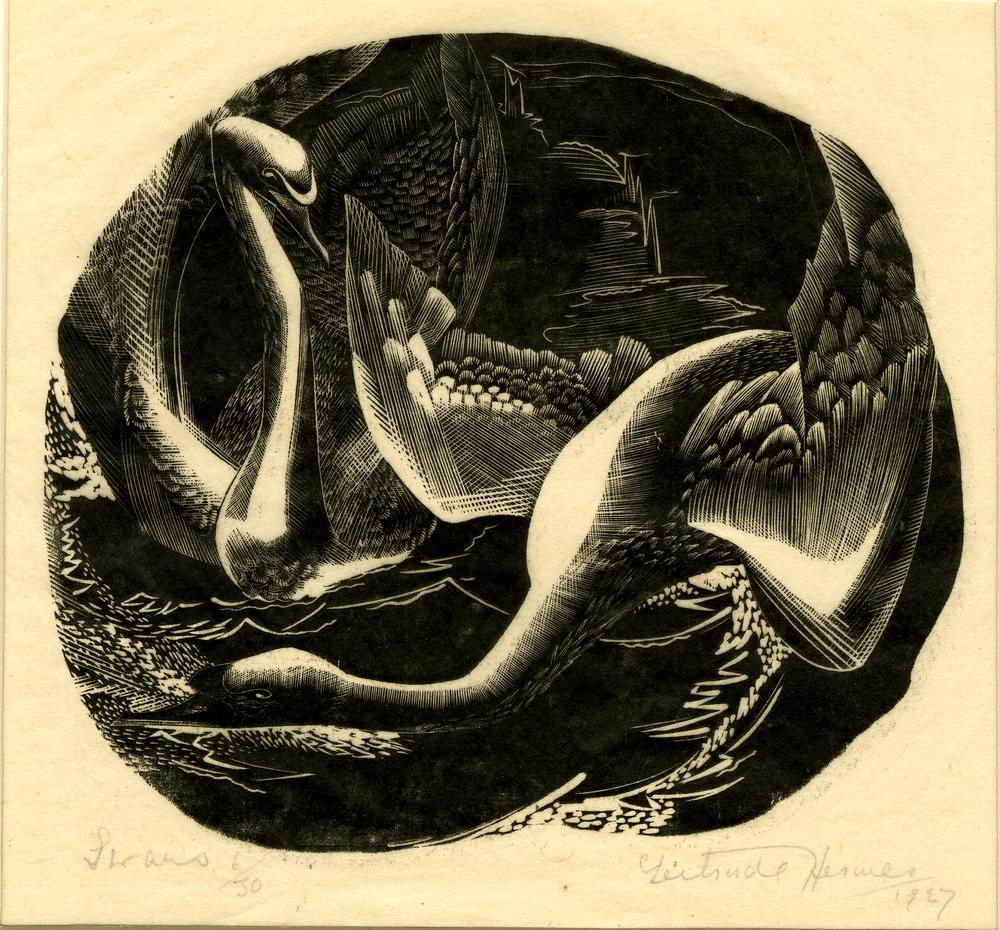

An exhibition where magnifying glasses were supplied. It started, of course, with Thomas Bewick and his tiny, intricate wood engravings. (I recall Jane Eyre’s delight in his illustrations.) Beatrix Potter, Eric Ravilious, Gertrude Hermes stood out. Not a blockbuster exhibition, but I don’t mean to damn it with faint praise when I say that what I enjoyed most was re-reading Peter Rabbit for the first time in almost 60 years.

The Bewick illustration is a little crude, but it reminded me of some of my thoughts as I walked beside Hadrian’s Wall yesterday – wondering if people in the inbetween centuries just thought of it as a bit of ruined wall.

Last night I saw the moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn for the first time. Also a close-up of the full moon, so large that it barely fitted in the eyepiece. We were very fortunate: it had been so murky a day that I had no expectation of clear skies – and, indeed, everything clouded over again just as we were finishing.

I started today by misreading the bus timetable. A mild, misty day with the promise of sunshine. I definitely didn’t want to wait two hours for another bus so set off on foot for a path that included a “Ford” marked on the map! The route I chose was cautious rather than direct (and, yippee, the dreaded “Ford” was furnished with a footbridge), and I reached Hadrian’s Wall at the Temple of Mithras. I had the impression from the map that this wasn’t a great stretch to walk – close to the road and the sound of traffic – but it was wonderful. I had the path to myself and I wasn’t expecting to come across the short section of wall still standing.

At Chollerford – far too early for the bus to Wark – I decided to catch a bus into Hexham for a coffee and a newspaper and return from there. A quite wonderful 24 hours.