Yesterday’s visit to the British Museum altered my focus today. I’d intended to see the exhibition on medieval women at the British Library, but now I was bursting to see a separate exhibition of some of the artefacts taken from the Library Cave at Dunhuang. I managed half an hour before a school group arrived and it was utterly fascinating.

How come I’ve never heard of Dunhuang?! But in a way I find my ignorance inspirational: there may be heaps of other wonderful serendipitous discoveries still to come my way.

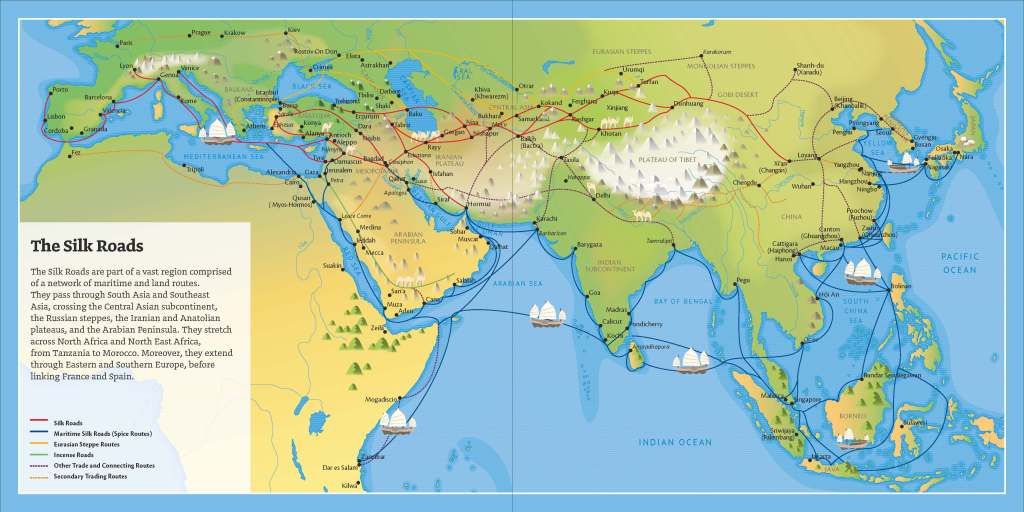

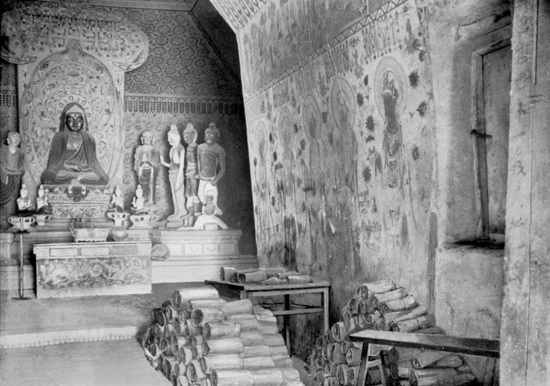

So: Dunhuang is an oasis town, once a garrison on the edge of the empire controlled by the Han dynasty. It has several Buddhist cave sites around, including the Mogao Caves (first caves dug out around 366 and more over the next thousand years), which look utterly amazing. The only – comparatively puny – comparison I could pull out from my own experience was Mystras or the monasteries of the Meteora.

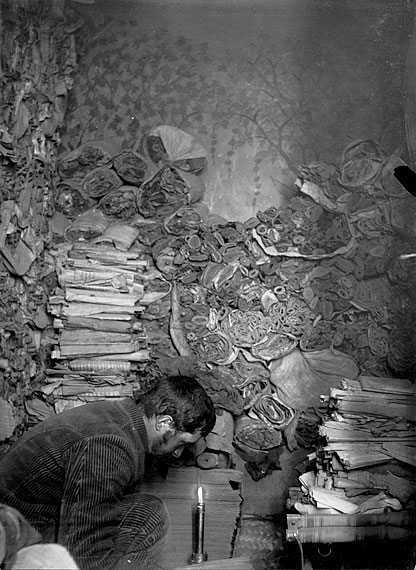

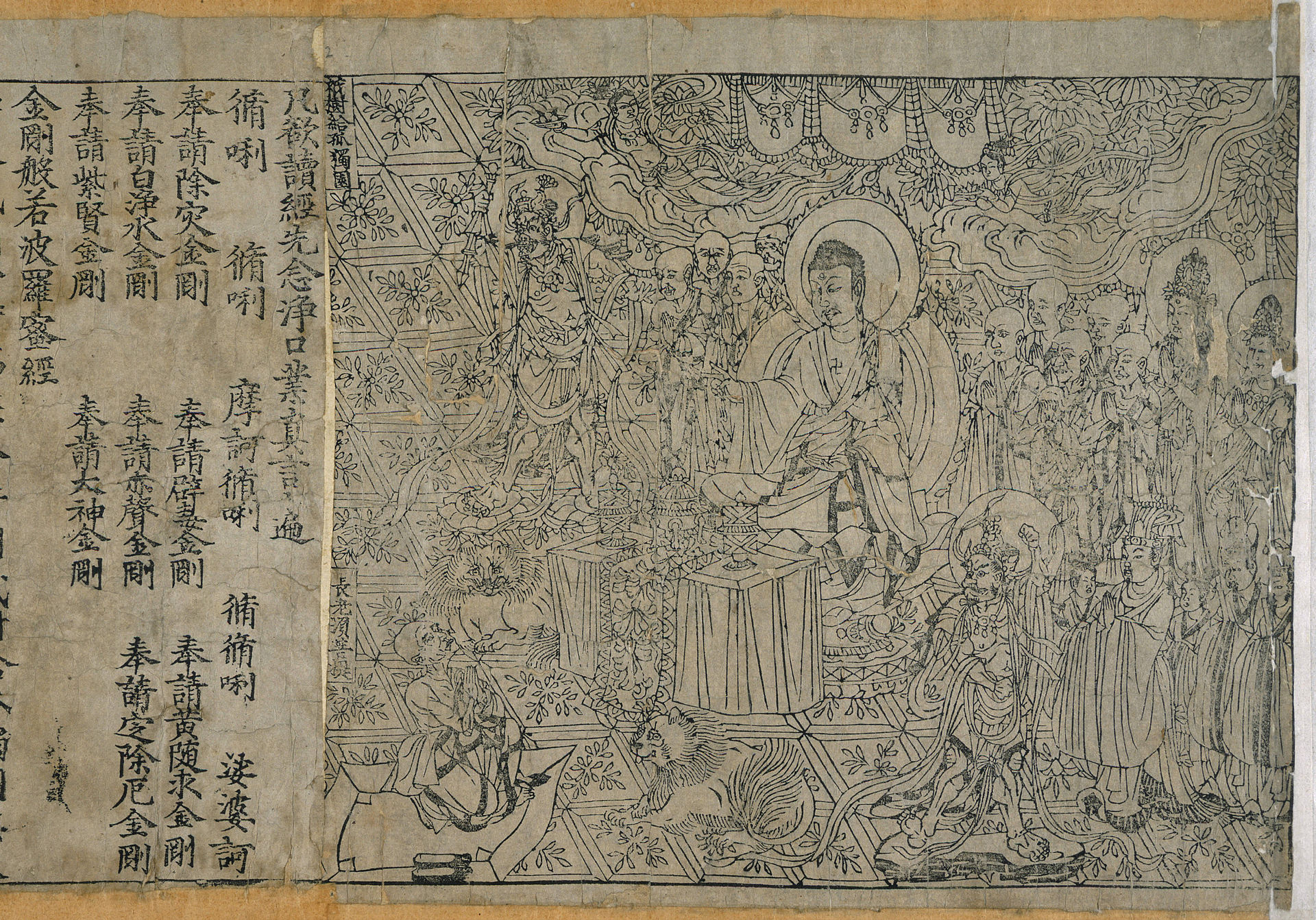

The Library Cave (cave number 17 of more than 700 caves) was discovered by a Taoist priest, Wang Yuanlu, in 1900. It contained some 50,000 documents of all kinds, both religious and secular, dating between 406 and 1002. Marc Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-British archaeologist (whose life story sounds fascinating), acquired many of them and brought them to Britain. This included – deep breath to take it in – the Diamond Sutra, the oldest complete printed book with a date in the world.

Which I took a photo of.

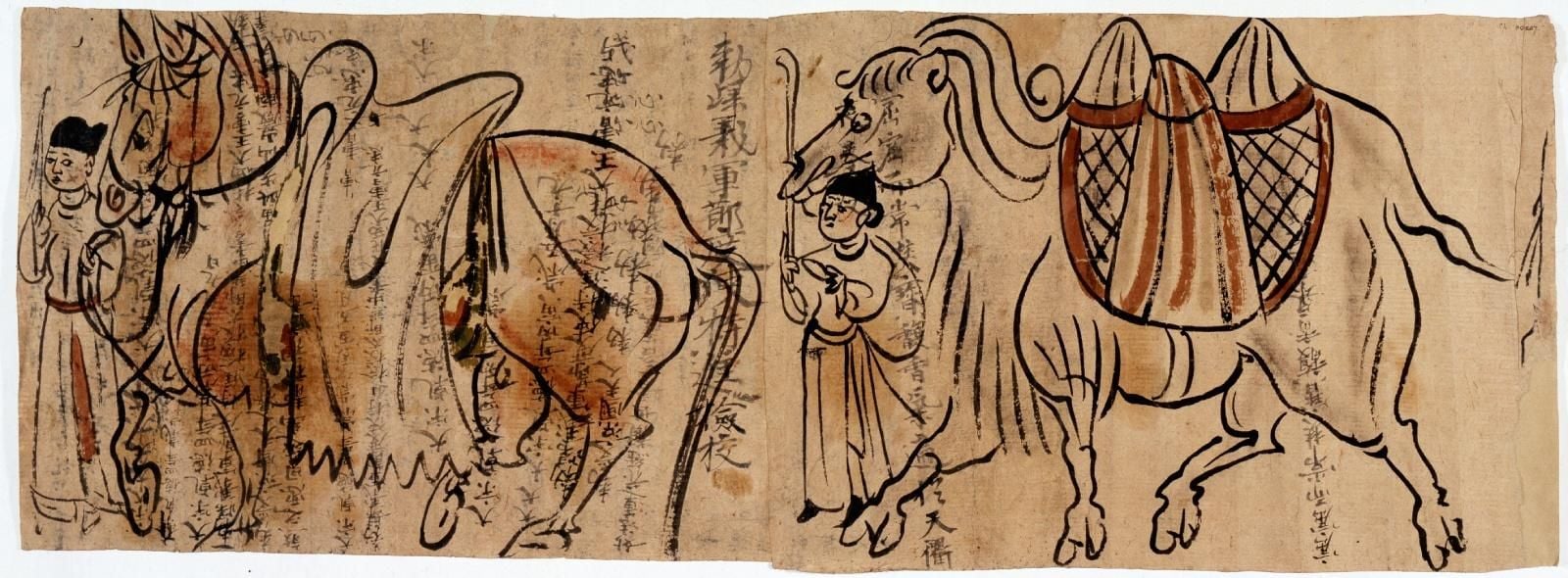

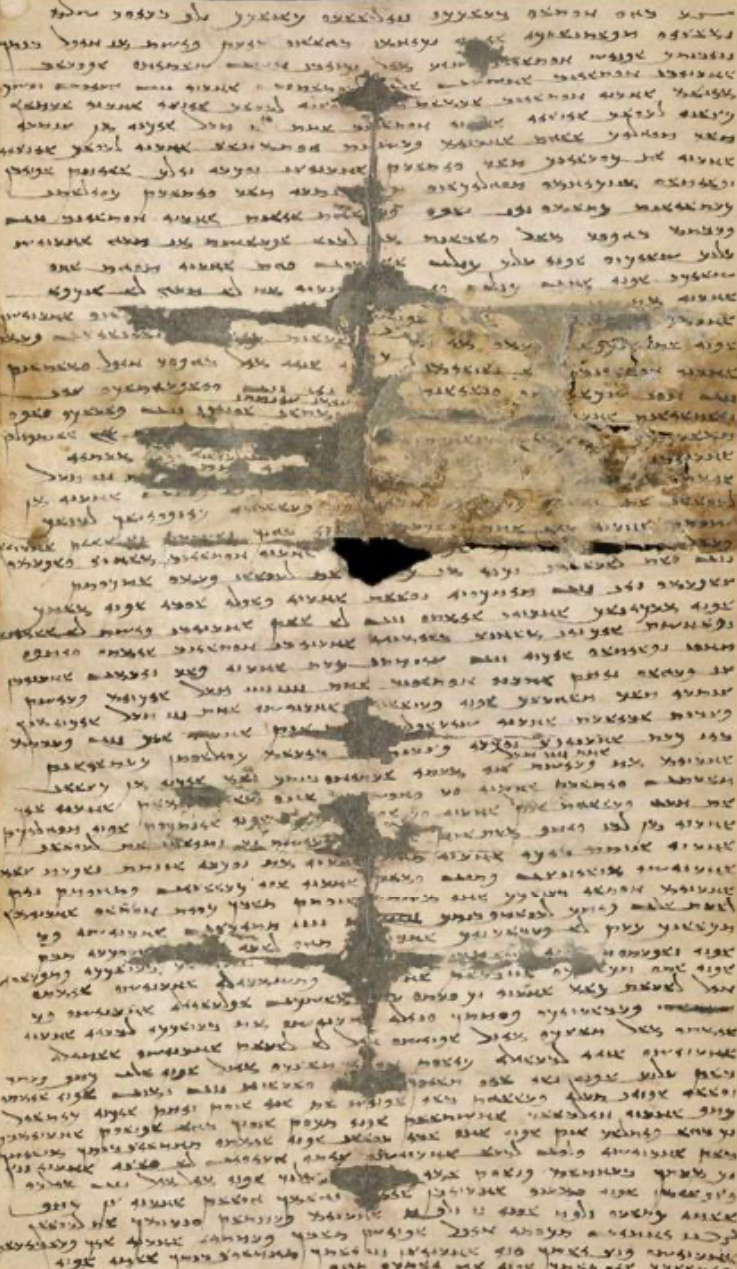

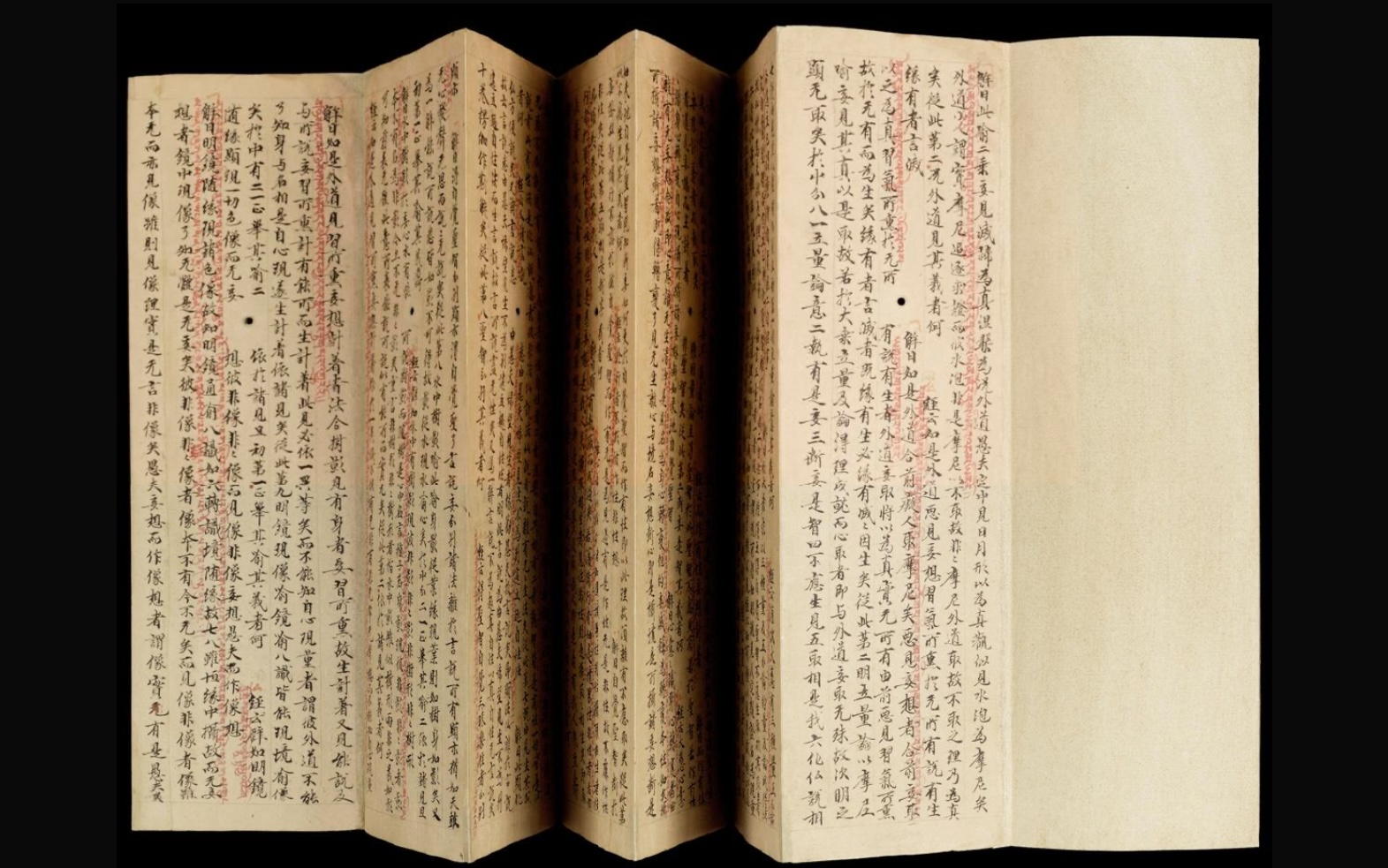

There were phrase books (crucial at this multi-lingual crossroads), Tibetan sutras copied out by local scribes (which gave an impression of what work was to be had), artists’ designs, letters between merchants and families, woodblock prints, almanacs, etc etc. Unable to understand a word, I focussed on the charm of the pieces: the holes in the much-folded letter from a merchant, the concertina-ing of a bilingual manuscript which could be read horizontally or vertically depending on the language.

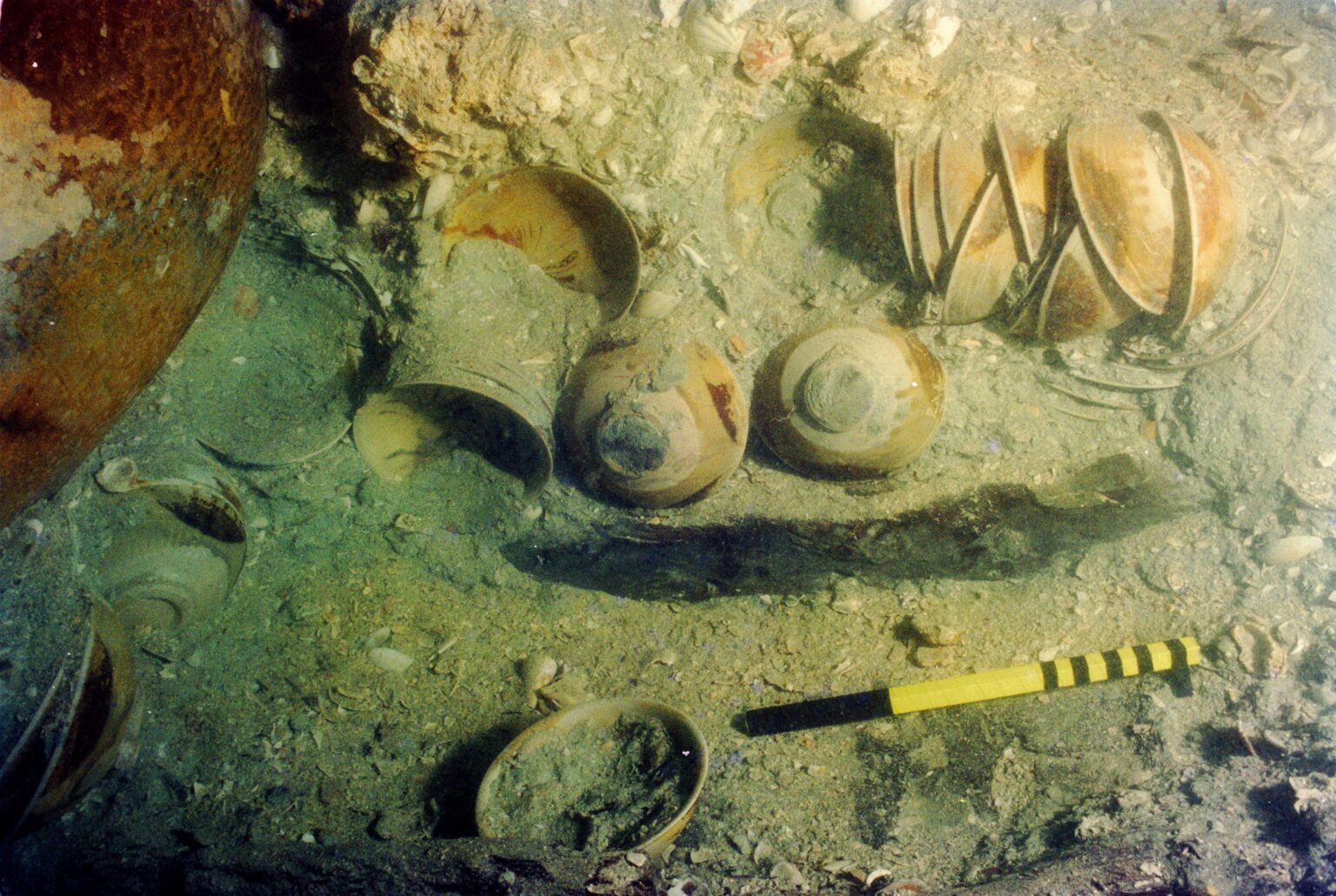

The exhibition underlined what I had grasped yesterday: that goods are not the only things to travel along trade routes. Religions, ideas and practices are just as significant.

After this, the exhibition on medieval women in their own words seemed dull and predictable. My only amusement at the time was in discovering that a charm made from weasel testicles was considered a contraceptive. I appreciate the scholarship that goes into all this, but, really, Jane Austen put the words into Anne Elliot’s mouth over 200 years ago:

Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands.

On reflection, that is a very unfair and sweeping judgement, for it did contain some astounding items: a letter dictated by Joan of Arc and signed by her, for example. And the thread of religious mysticism kept me wondering: was Margery Kempe unusually pious, a charlatan, or had she found her own way to escape the bonds of a medieval woman’s life?