I’m going to the Vanessa Bell exhibition in Milton Keynes tomorrow, so, as prep, I had a hankering to visit the Radev Collection exhibition at the Charleston in Lewes. This part of the Charleston is housed in a 1930s disused council building within spitting distance of the railway station, and the Radev Collection is of 19th/early 20th century British and French art. The origins of the collection are almost as interesting as the artworks themselves.

But first I had to get there. Change at East Croydon on the way out and Haywards Heath on the return – places that were hitherto merely names to me. As the train moved away from London I eagerly looked out of the windows to see the countryside and observe how it differed from what I am used to . . . but where on earth was it? It seemed ages before houses gave way to greenery, which set me to thinking of how George Orwell and E M Forster (more of him later) railed against the spread of interwar ribbon development. Their laments always struck me as rather paternalistic and snobbish – people must be housed after all – but today I saw their point. Perhaps we all turn nimby as we age and pay off our mortgages. “Going, going” indeed.

And then I got sidetracked by Lewes itself. It’s charming! It even has a castle (I really had no idea). Steep streets, Georgian buildings, knapped flint (even for the Kingdom Hall!), interesting vernacular architecture, chalk outcrops in the background, a history of brewing . . . it looks like once upon a time it was a self-contained, busy county town, an economic and administrative hub. I’m not sure that that is still the case, and quaintness only gets you so far . . . but all I can say after a short trip is that I liked it.

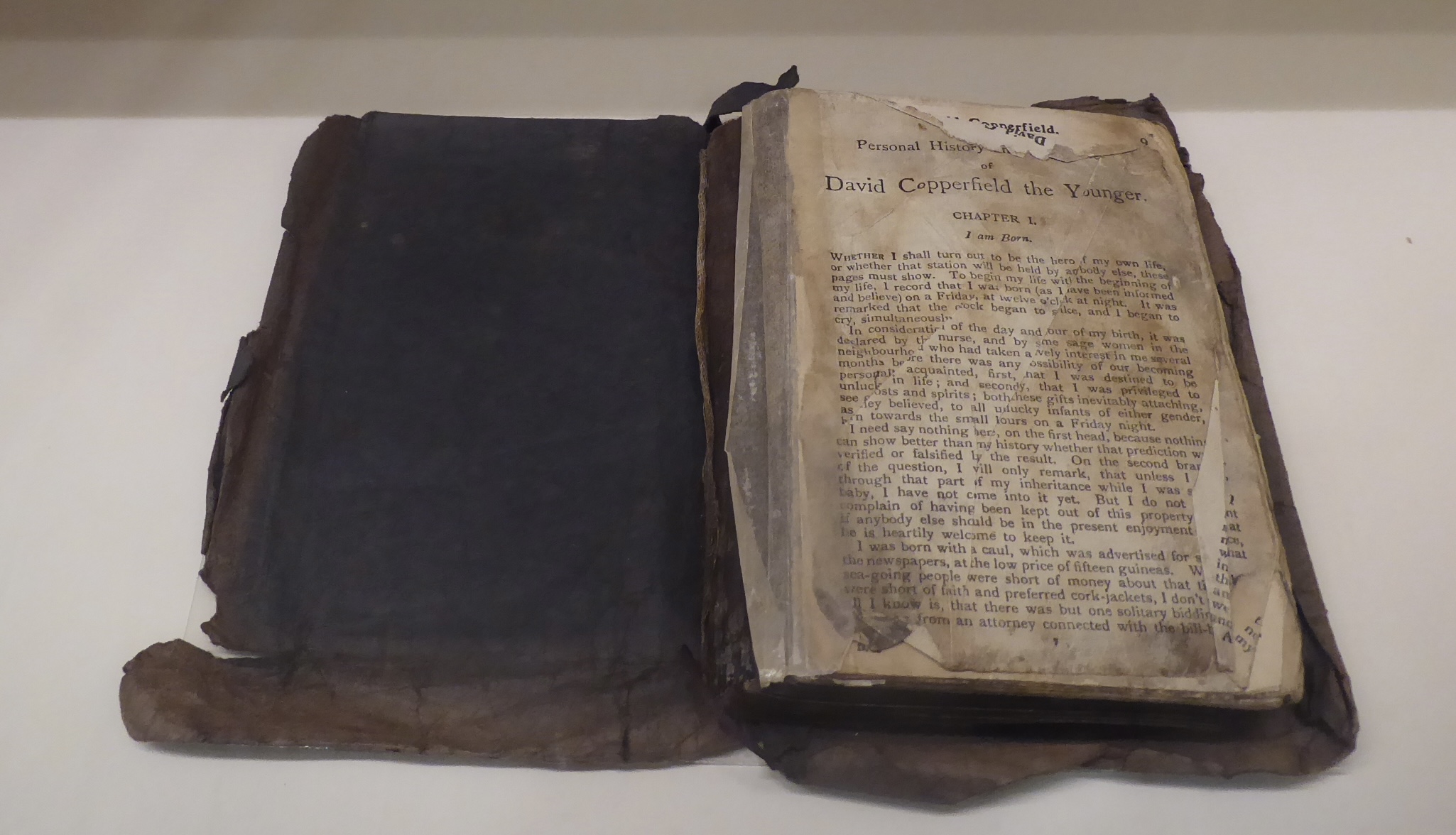

And so to the Radev Collection. The difficulty about the Bloomsbury Group and its satellites is keeping track of who had affairs/was friends with whom, because it does actually matter. So, Edward Sackville-West, a music critic, started collecting in 1938. He left his collection to a former lover, Eardley Knollys, art critic/dealer and artist who already had a collection of his own. Along with Desmond Shawe-Taylor, they had bought and created a salon at Long Crichel House in Dorset. (The former rectory – a nice irony.) Mattei Radev was a young Bulgarian refugee who stowed away on British ship in Istanbul and was granted asylum in 1950. I surmise he must have had great charm in his youth – even though the horrible painting of him by Maggi Hambling in later life does suggest ‘the worms crawl in, the worms crawl out” – for he found his way into Knollys’s life and was assisted by Knollys to establish himself as a picture-framer. After Knollys’s death Radev inherited the whole collection, which then passed to his civil partner on his death.

Oh yes – E M Forster also fell in love with Radev for a while.

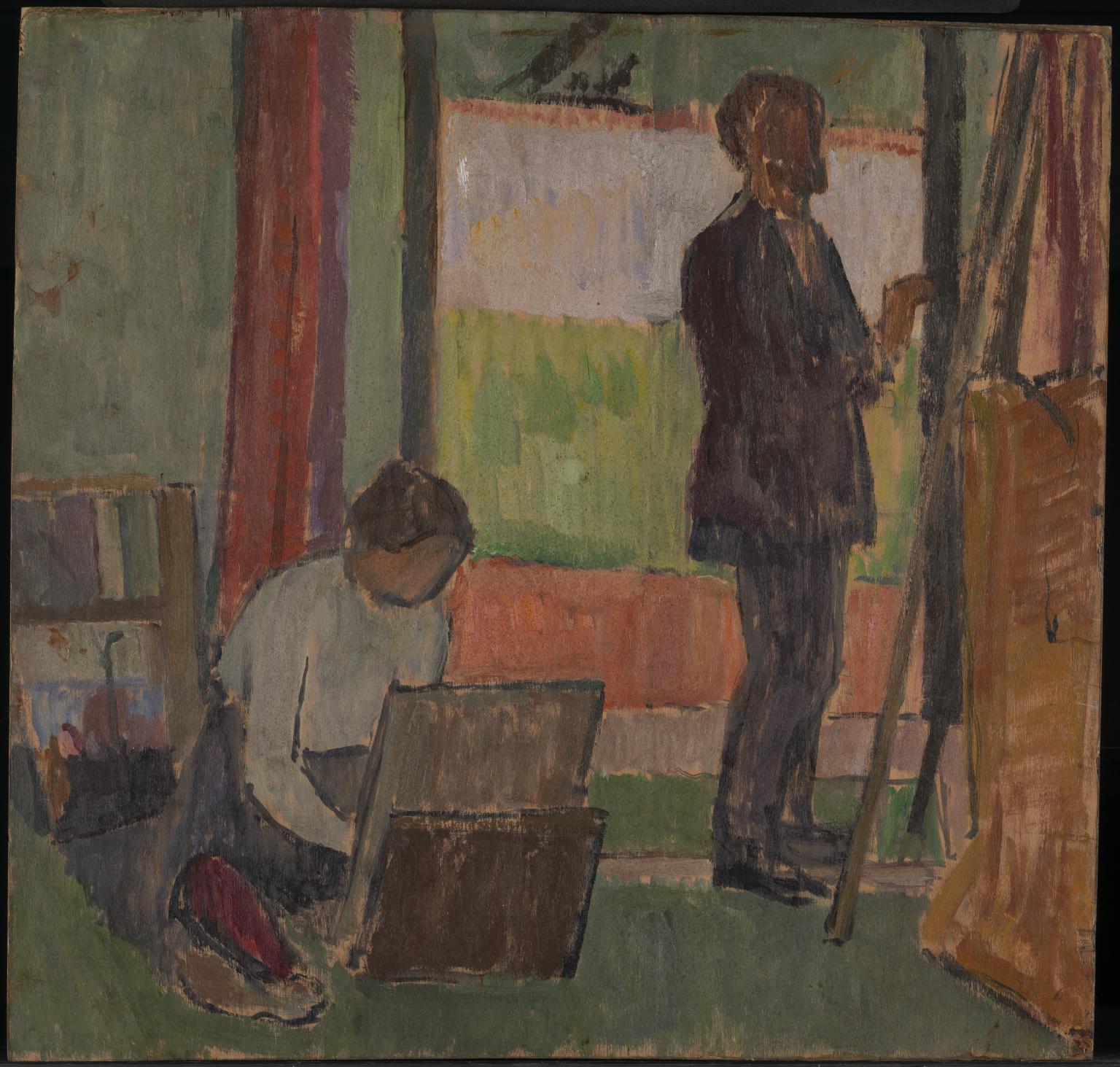

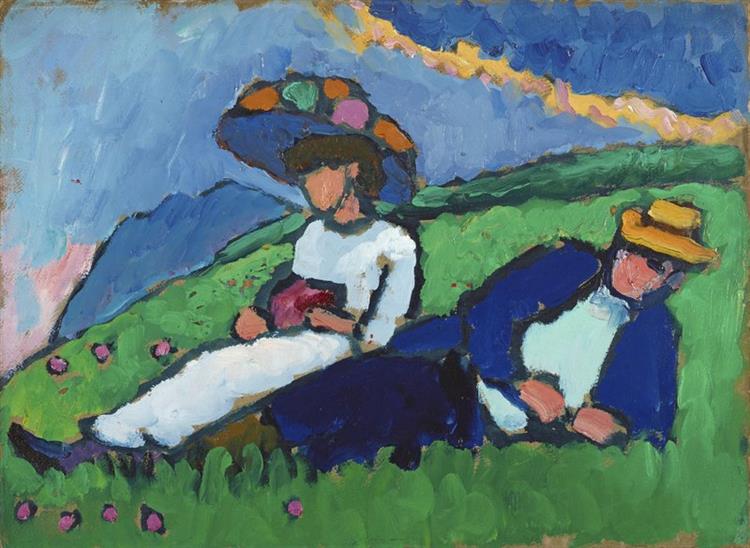

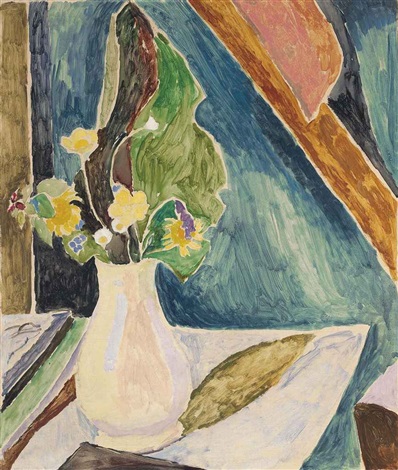

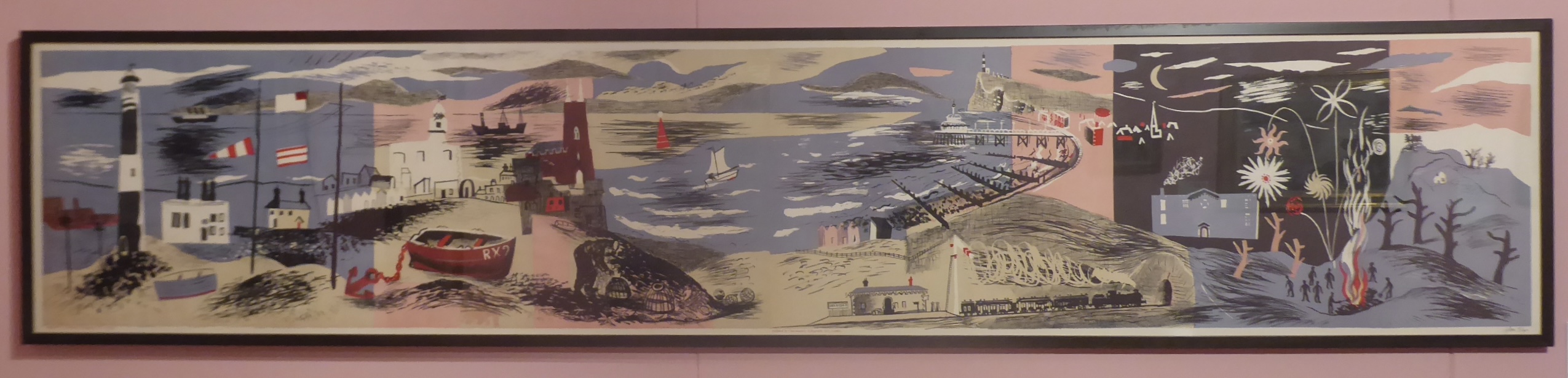

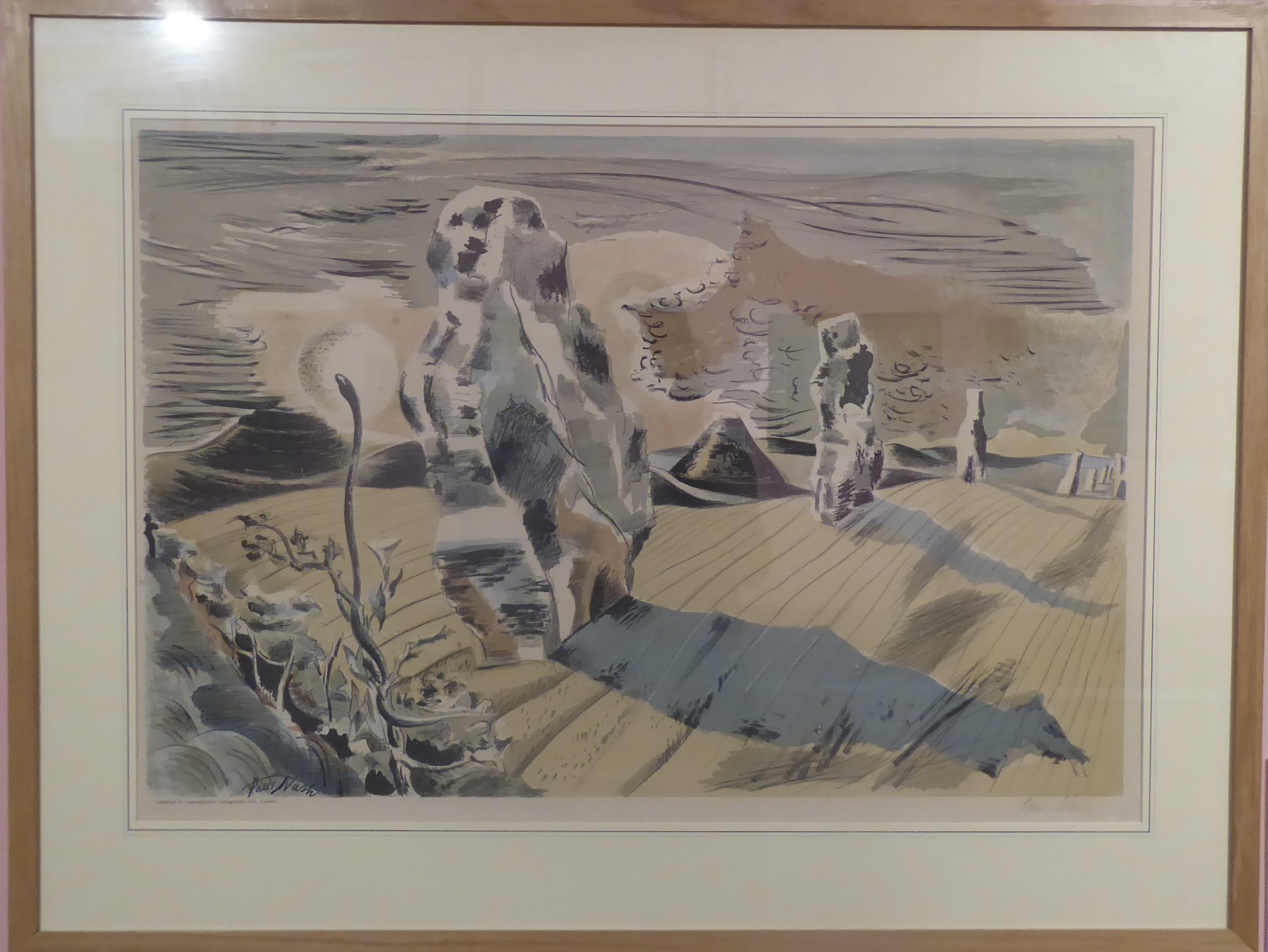

And the paintings? I wandered amongst them and confirmed my likes and dislikes – and then tried to examine why. I am still unimpressed by Vanessa Bell (such dull daubs), I still don’t care for Matthew Smith (nasty colour combinations), Eugéne Boudin’s use of oil paint is masterly, I can’t think why Alexej von Jawlensky’s colours are so appealing to me but they are, and I am beginning to like Graham Sutherland. Then the lithographs by John Piper and Paul Nash – I think I grew up on those types of illustrations and I felt very drawn to them, particularly since the Nash was inspired by the stones at Avebury.